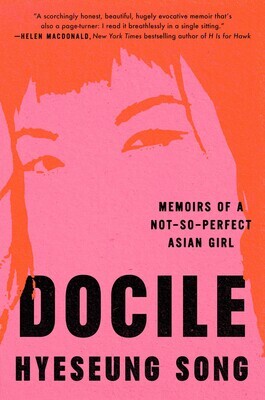

A Review of Hyeseung Song’s Docile (Simon & Schuster, 2024)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) uttararangarajan

uttararangarajan

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Uttara Rangarajan

As a fellow Korean American, Hyeseung Song’s Docile (Simon & Schuster, 2024) hit particularly close to home. I always cite erin Ninh’s work (her biography linked below) when it comes to memoirs like these ones, because the model minority dynamic that Asian American migrants themselves promote can be so utterly destructive. Such is the case in Docile. We shall let the marketing description do some work for us: “A daughter of Korean immigrants, Hyeseung Song spends her earliest years in the cane fields of Texas where her loyalties are divided between a restless father in search of Big Money, and a beautiful yet domineering mother whose resentment about her own life compromises her relationship with her daughter. With her parents at constant odds, Song learns more words in Korean for hatred than love. When the family’s fake Gucci business lands them in bankruptcy, Song moves to a new elementary school. On her first day, a girl asks the teacher: ‘Can she speak English?’ Neither rich nor white, Song does what is necessary to be visible: she internalizes the model minority myth as well as her beloved mother’s dreams to see her on a secure path. Song meets these expectations by attending the best Ivy League universities in the country. But when she wavers, in search of an artistic life on her own terms, her mother warns, ‘Happiness is what unexceptional people tell themselves when they don’t have the talent and drive to go after real success.’ Years of self-erasure take a toll on Song as she experiences recurring episodes of depression and mania. A thought repeats: I want to die. I want to die. Song enters a psychiatric hospital where she meets patients with similar struggles. So begins her sweeping journey to heal herself by losing everything.”

One of the sustained issues in this text is Song’s desire to find her own path and identity independent of the one expected of her by her parents. The problem with putting her own interests aside for those of others is that it becomes a habitual form of self-denigration that undoubtedly impacts her psychic state. This memoir also brings to mind the work of James Kyung-jin Lee in Pedagogies of Woundedness, which looks to narratives of illness and debilitation (information also linked below) to remind us that Asian Americans don’t only achieve and progress. Never is this non-linear progression more evident than when an Asian American must balance model minority expectations alongside the development or germination of illness. In this case, Song occasionally experiences bouts of depression, which are alternately followed by periods of stability and even of major creative profusion. For those versed in the DSM, you’re already beginning to think about the possibility that Song may actually be bipolar. Indeed, Song will finally get this diagnosis later in life, which begins to piece together some of the most challenging parts of her life. But there are lots of unprocessed sections of this book, which make it particularly difficult read (and perhaps important for some to consider through a trigger warning before reading). For instance, a year in Korea that was meant to help Song recalibrate after needing a break from Princeton also comes with it multiple instances of sexual assault. She will also attempt suicide at multiple points, all the while attempting to navigate parental influence alongside her own interests. Even a seemingly stable long-term relationship is upended when Song realizes that she is not finding herself within that coupling and that she needs to relinquish it in order to address more fully what is ailing her. The concluding arc will not give us much resolution, but readers will be buoyed by the knowledge that Song has come to a place of significant self-reflection that has enabled her a level of dynamic equilibrium; she comes to understand her connection to her family as a complicated one, while she continues to advocate for the things that are important to her fulfillment. It is this final aspect that is part and parcel of Song’s journey toward healing: that she herself must find her way whether or not it is her parents or anyone else backing her. In this sense, in some ways, it almost feels as though Song finds her rebirth only after many decades of what others would consider to be incredible achievement. Song might say that her path has only just begun. At the end of the day, this memoir is yet another monumental takedown of the model minority myth and one that should be directed toward Asian Americans themselves who do not realize that the cost of upholding this ethos is so much potential destruction.

Buy the Book Here

For more on Ninh’s work, see this

For more on James Kyung-jin Lee’s work, go here

comments

comments