Never mind looks that can kill, how about books that will?

No, this is not an intro to a horror movie, although I’ve just given myself an idea!

It’s been a while since we’ve taken a look at colours and how intimately they’re tied to life, literature and storytelling. Well, the perils of the colour green are in the news.

For a species that’s supposed to be the smartest on the planet, we humans can be remarkably stupid in our pursuit of fashion and décor.

The quest to bring vivid colours to artwork, clothing, wallpaper and even book covers became entangled with chemistry, and the end results were lethal.

In 1775 a pharmaceutical chemist named Carl Wilhelm Scheele played around with a solution of sodium carbonate, commonly known as washing soda or soda ash. He slowly added arsenious oxide, which contained – guess what? Arsenic. After putting that into a solution of copper sulfate, it produced a pretty green result, which he named after himself: Scheele’s Green.

It was more brilliant and durable than current green tints, and became an extremely popular colour to add to just about anything – textiles, wallpapers, paints, candles, bookbindings, children’s toys and even some sweets.

There was another popular green pigment, created in 1814, called Paris green, or Emerald green, which had a pretty bluish undertone.

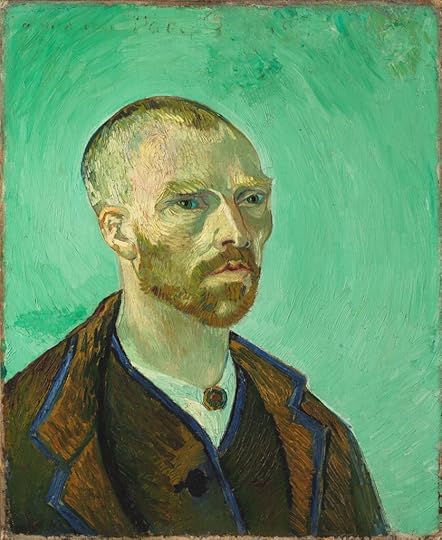

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait (Dedicated to Paul Gauguin), September, 1888. The vivid green background has an undercoat of Paris green. You have to wonder whether use of this pigment contributed to the artist’s psychological difficulties. By Vincent van Gogh – 1. Web Museum, (file)2. Google Art Project, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9857

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait (Dedicated to Paul Gauguin), September, 1888. The vivid green background has an undercoat of Paris green. You have to wonder whether use of this pigment contributed to the artist’s psychological difficulties. By Vincent van Gogh – 1. Web Museum, (file)2. Google Art Project, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9857 Although the toxicity of arsenic compounds wasn’t generally well known at the time, someone figured it out – they began making insecticides with both pigments. Paris green was officially the first chemical insecticide made. It was even dangerous to manufacture.

But the vibrancy of the colours was apparently too good to resist, and green-tinted articles began showing up everywhere.

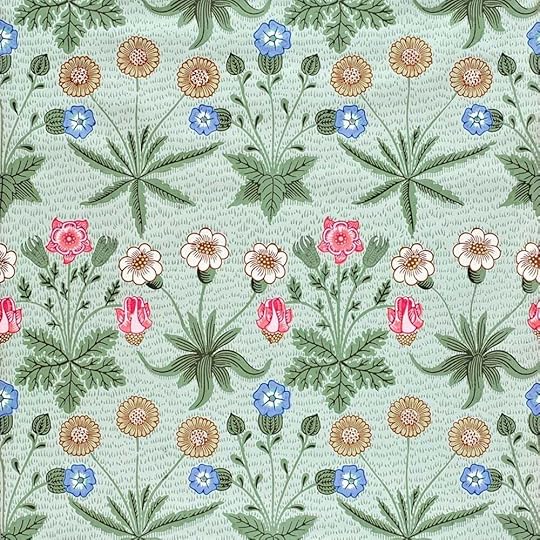

Even designer-artist William Morris, as the heir to a copper mine (which conveniently produced arsenic dust as a byproduct), used these greens in his wallpaper. Although as an activist he campaigned for safer working conditions for textile manufacturers, there wasn’t an organic dye that could replicate the beautiful greens of the arsenic/copper based pigments, and he refused to believe claims that they could be dangerous, even when doctors told him flat out that his miners were suffering from arsenic poisoning. Morris claimed they “were bitten by witch fever”, as in, making it up.

Daisy wallpaper designed by William Morris. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/384017, public domain

Daisy wallpaper designed by William Morris. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/384017, public domainBut soon there were reports of ladies in green gowns passing out, children wasting away in rooms painted green, and newspaper printers being overcome by toxic vapours. Some European countries began banning these arsenic-containing tints, but use of them continued for several decades, until a young maid tasked with dusting artificial greenery died from arsenic poisoning. The newspapers reported her illness in great detail, including the fact that her eyes and fingernails had turned green. It must have been a horrible death.

Throughout the 19th century, Paris green and similar arsenic pigments were used in books in multiple ways – cloth coverings, decorations and interior illustrations. And many of these antique, and highly toxic books, still exist in collections around the world.

In 2019 two staff members of the Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library in Delaware found a book in one of its own collections that contained Paris green. Now if you still think being a librarian is a stuffy job, check this out.

Melissa Tedone, head of library materials conservation at Winterthur, was working on a copy of the 1857 book Rustic Adornments for Homes and Taste. She noticed, under a microscope, that bits of the green pigment-dyed starch used to strengthen the bookcloth were starting to flake off.

Bookcloths became a less expensive alternative to leather bindings in the mid-1800s. The advantage of the cloth is that it allowed for some beautiful tinting, and one of the most popular colours was Paris green. It’s been estimated that in twenty short years, before the colour went out of fashion, tens of thousands of books were made with it.

Melissa provided samples of her green flakes to the museum’s laboratory head, who a cool machine called an x-ray fluorescence spectrometer to examine the flakes, and discovered that they contained copper and arsenic.

The Paris green bookcloths could cause arsenic poisoning in people who handle them often, i.e. librarians and researchers. Paris green flakes into a dust that’s invisible to the naked eye. There are a number of other toxic substances used in pigments, including lead and mercury, that the Project has also identified.

The Poison Book Project was created to identify toxic books in other institutions so that librarians there could start protecting anyone who might handle them. Its research team has developed an emerald green color swatch bookmark, which doesn’t offer definitive proof of the presence of Paris/Emerald green in a book, but provides a visual guide to help either private individuals or institutions to narrow down whether it’s likely in one or more of their books. According to the project’s website, there’s currently a long waitlist for the free bookmarks.

The University of St. Andrews has recently made the news for inventing a gadget that can quickly identify arsenic in green-covered books from the 19th Century. A significant issue for many institutions has been that they haven’t had the resources to test or have tested any such book in their collections. As a result, those books are being restricted from use. The researchers at St. Andrews wanted a practical solution for surveying the thousands of historic books in their collection.

Using a spectrometer that detects minerals in rocks, they were able to have their physics department create a portable, non-destructive instrument that flashes red if a book is poisonous. It’s already been used to survey the thousands of books in the St Andrews collections and in the National Library of Scotland.

The toxic antique books will become increasingly dangerous as they age and deteriorate, and the team hope to share their design with other institutions around the world, to allow for identification, safe storage, and putting precautions in place for patrons to be able to continue to enjoy them.

As always, the moral of the story is that health and safety comes before art. But humans have a history of not learning from our mistakes. If you happen to have an antique book in your home with a vivid green cloth cover, you might want to bag it up and have it checked out, because in that case you’d absolutely want to judge the book by its cover.