This Gilded Age holdout house still stands because the widow who owned it said no to developers

Is West End Avenue the holdout capital of Manhattan? Peeking out between many blocks of stately prewar apartment buildings are several lone Gilded Age row houses that managed to evade the bulldozer.

Some are restored and lovely, others shabby chic. All have backstories. But a strong-willed widow steeled by a tragic family drama may have been the reason the slender row house at 249 West End Avenue, just south of 72nd Street (above), is still standing.

First, let’s dial back to 1893. That’s when No. 249 got its start as a new and fashionable middle house in a group of five elegant attached homes (below advertisement).

Romanesque Revival in style, the three middle row houses had bow fronts and terraces in front of the rounded windows on the third floor. The two outer dwellings stood like handsome sentries framing the inside three. All had unusual small porthole-like windows on the fifth floor.

The row was designed by Clarence True, an architect and builder who brought his fanciful architectural vision to West End Avenue and Riverside Drive in the 1890s, just as development was ramping up on these recently opened streets.

True liked building clusters of delightful row houses that rebelled against the staid and uniform brownstones of the 1860s and 1870s. Through the early 20th century he put up hundreds of these eclectic dwellings in the area, which were in high demand by well-heeled buyers.

His row houses became defining features of Manhattan’s newly elite West End neighborhood—today known as the Upper West Side.

Ferdinand Huntting Cook and his wife, Mary Aldrich Cook, weren’t the first residents of No. 249. After the house was built, it was owned by a man named William Nesbit. Joseph Powell, a cigar manufacturer, was the next owner; he died of pneumonia there.

At some point after Powell’s death, the Cooks bought the row house, turning it into a family home for themselves and their five children. It was a convenient location for the two boys in the household, who attended nearby Collegiate school.

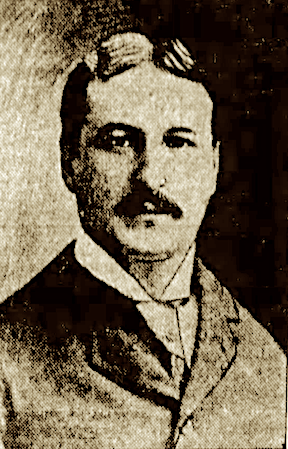

Sadly, all was not well with Ferdinand Cook. A descendant of an old and wealthy New York City family, Cook was employed by the Department of Parks and had dabbled in other businesses. In 1913 he was 50 years old and later described by his brother Henry Cook as “ill and depressed.”

Exactly what troubled Ferdinand Cook isn’t known. But his depression led to a tragedy that began on January 3, 1913, when he told Mary he was heading out to Park & Tilford’s, a high-end grocery and liquor store on 72nd Street and Columbus Avenue . . . and never returned.

Mary was understandably concerned. She alerted the police and hospitals, thinking he may have been hurt in a windstorm the night he disappeared. Newspapers covered the story, interviewing family members. “It is possible that he suffered an attack of amnesia and wandered off,” Henry Cook told a reporter from the New York Times. “We have no clue.”

As the days went by, Mary became “worn out and ill from worry over his absence,” per the Times. Descriptions of Ferdinand Cook noting his “iron-gray hair,” that he weighed about 150 pounds, wore two rings and a gold watch, and “did not have more than $18 in his pockets.”

A month later, her husband’s body was found in a wooded area in Queens. By his side was a gun; he apparently shot himself in the temple. After learning the news, Mary Cook “was in a hysterical condition,” wrote one Brooklyn newspaper.

If Mary ever spoke of her heartbreak and pain, her words were not recorded in any newspaper account. Apparently, life went on for this 43-year-old widow. Through the 1920s, the engagements of two daughters and a son were announced. The brides held their wedding ceremonies at All Angels’ Church on West End Avenue and 80th Street.

Her children were grown, and her neighborhood was also changing. The lovely row houses Clarence True and other developers had built were being marked for demolition, sold to make way for a new kind of New York housing: the tall apartment residence.

Mary “repeatedly declined offers to sell the house, even as similar homes to the north and south were demolished for construction of large-scale apartment buildings,” according to the West End-Collegiate Historic District Extension Report.

The first offer to sell may have come just a few years after her husband’s suicide, as the building to the north, 255 West End Avenue, was completed in 1917. On the south side, development of 243 West End Avenue was underway in the early 1920s.

It stands to reason that developers of both buildings offered Mary money to vacate—money that the owners of the four neighboring row houses took. For reasons only she knows, Mary held on to the home were she mourned her husband and raised her family.

After Mary Cook died in 1932, the holdout house—smushed between two giants and useless to developers—changed hands again. “During the 1930s, and possibly extending into the 1940s, the Continental Club was located within the building, offering lectures, musical performances, and other cultural events,” notes the Historic District Report.

Inside the Continental Club was also the Uptown Gallery, “where works of cutting-edge artists including Adolph Gottlieb and Mark Rothko were shown.”

No. 249 returned to residential use in the 1950s and was eventually converted into apartments. Recently it was covered in scaffolding, some of which remains on the first floor, blocking it from street view.

But you don’t need to see the front entrance to recognize what a jewel this row house is. Thanks to decisions made by Mary Cook, developers were forced to build their behemoths around her narrow dwelling, preserving it as part of the cityscape.

More than 130 years after the house and the four others in the row made their debut, it’s the only survivor.

[Second image: NYPL Digital Collections; fourth image: Brooklyn Eagle; sixth image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services]