Crafting Killer Short Story Arcs.

The other day, I spotted a short story competition with a five-day deadline.

Naturally, my brain—ever the optimist—whispered, “Hey, why not turn that pilot episode of ‘Crime Cleaners’ into a short story?” Spoiler alert: my brain lied.

Because I forgot the cardinal rule of writing: the shorter the piece, the harder the punch.

Compressing a character arc, emotional payoff, and satisfying resolution into 3,000 words?

It’s like trying to fit a wedding dress, two cats, and a live saxophonist into a shoebox.

It can be done, sure, but there will be casualties. A misplaced veil. A disgruntled cat. A jazz solo in the key of regret.

So, what did I do instead of writing? Procrastinated, of course—with style.

I embarked on a valiant quest called “Research” that mostly involved reading excellent short stories while telling myself it was all part of the process. I never entered the competition.

But I did start a new monthly habit: writing one short story a month. Here’s what I learned from my noble rabbit-hole expedition.

#1 – Pressure Cooker: Start With Heat.

In short stories, there’s no time for leisurely introductions or meandering exposition. Drop your character into boiling water on page one.

That pressure—external or internal—forces the story forward and your character inward. The situation should be tense enough to demand action, even if that action is quiet or internal.

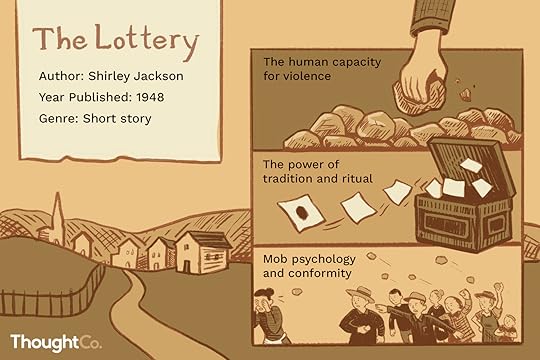

Think of Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery.”

A small town gathers for an annual tradition. Kids are laughing. Adults are gossiping. But there’s a hum of unease. Enter Tessie Hutchinson, breezy and late, joking with the crowd.

But when the ritual’s true horror (ritualistic stoning, anyone?) surfaces, she screams, “It isn’t fair, it isn’t right!” In just a few pages, her belief in tradition gets eviscerated. Boom: arc delivered.

Short stories thrive on urgency. Whether that urgency comes from a ticking clock, a tense relationship, or the slow dawning of an existential crisis, the key is to light the fuse early. Let the flame catch.

#2 – Start With a Flawed Lens.

#2 – Start With a Flawed Lens.

Your character doesn’t need to be broken, but they should see the world through a slightly cracked lens.

That core belief—whether it’s “people are inherently good” or “if I’m not nice, I’ll die alone with cats”—is your starting line. The arc, then, is the slow (or sudden) shattering of that belief.

In Kristen Roupenian’s “Cat Person,” Margot believes being agreeable is safer than being honest. She goes on a date with Robert, ignores her gut instincts, and tries to keep things polite.

By the end, after enduring his emotional whiplash and receiving a jaw-dropping final text, she has a moment of hard-won clarity: maybe likeability isn’t worth her self-respect. It’s subtle, but you feel the shift.

A character’s flawed belief doesn’t have to be destructive. Sometimes it’s just outdated or incomplete. However, challenging that belief, especially under pressure, is where the story truly unfolds.

#3 – Cast Small, Hit Hard.

Short fiction isn’t the time for a sprawling ensemble cast. You need one or two well-drawn characters and maybe a barista for flavour.

Every supporting role should serve the main character’s journey—either by poking their flaw or nudging them toward change.

Take Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants.” It’s just a man, a woman, and a drink while they wait for a train. They dance around the topic of abortion without saying the word.

The woman begins the story unsure and deferential. By the end, her silences have weight. Hemingway never shouts the arc—he whispers it, and it lands.

Every interaction in a short story should be meaningful. Even a single line from a side character can act as a turning point if it lands at the right moment.

#4 – Tiny Shifts, Titanic Ripples.

#4 – Tiny Shifts, Titanic Ripples.

A short story arc doesn’t need to end with your character moving to Bali and starting a kombucha empire.

Tiny shifts count. A new realisation. A decision they wouldn’t have made 10 pages ago. The smallest internal pivot can resonate deeply.

In Karen Russell’s “St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves,” the narrator assimilates into human society, leaving her feral sister behind.

She doesn’t become a villain or a hero. She adapts. Survives. And realises what she’s lost. The change is small but devastating.

Think of it like this: if the story starts with the character looking through a foggy window, by the end, they may wipe just one corner clear. That’s enough. That’s movement.

#5 – Trust the Reader’s Brain.

Don’t spoon-feed. Short stories thrive on implication. Let your readers lean in, make connections, and fill in the emotional blanks. They’ll love you for it.

You’re building a collaborative emotional experience, and readers are smarter than we sometimes give them credit for.

Jhumpa Lahiri nails this in “A Temporary Matter.” A grieving couple reconnects during nightly blackouts. We hope, foolishly, that they’ll mend.

Then, one confession too far. The lights come on. And we just know: this is the end. Lahiri never needs to say it outright. She lets the silence do the heavy lifting.

Subtext is your best friend in a short story. Use it. Trust the reader to hear what’s not being said.

#6 – Objects Have Feelings Too.

When there’s no room for a character’s inner monologue, symbolism and setting step in like the understudies they are.

A favourite object, a shifting environment, a repeated image—these become the mirrors of internal change.

Ken Liu’s “The Paper Menagerie” breaks hearts using origami animals. Jack pushes away his Chinese heritage and his mother.

After her death, a note hidden inside a paper tiger reveals her sacrifices. The origami—once just paper—becomes sacred. Jack doesn’t need a monologue. His heartbreak speaks through the folded creatures.

If your character can’t say what they feel, show it in how they touch a scarf, how they linger in a childhood bedroom, how the weather changes as their perspective does. Make the world their diary.

#7 – Don’t Resolve. Resonate.

#7 – Don’t Resolve. Resonate.

Forget tidy bows. Forget big finales. The best short stories end like a haunting melody—lingering, not wrapping.

Leave your readers with an emotional echo, not a how-it-all-turned-out PowerPoint slide.

In George Saunders’ “Escape from Spiderhead,” a prisoner refuses to harm others, choosing death instead.

We don’t know what will happen next in the world. We just know he changed. He reclaimed his agency.

That’s what sticks. Not the facts. The feeling.

A short story’s power often lies in what it doesn’t say. Let your final paragraph be the emotional aftershock, not the cleanup crew.

In Short (Pun Intended…)So, what makes a character arc land in a short story? It’s not the size. It’s the sharpness.

Give us one crack in the surface, one ripple in the mirror. Make it matter.

Start with pressure. Give us a flawed belief. Keep the cast tight. Let change whisper.

Let silence speak. Let objects carry memory. And above all, don’t tie it up—let it ring.

If, by the end, your character sees themselves or their world just a little differently—if we, the readers, feel that difference in our bones—then you’ve done it. You’ve pulled off the literary equivalent of magic in miniature.

And if not? There’s always next month’s short story. Just don’t start with a 60-page pilot script, okay?

Or do. Just be prepared to share your shoebox with a saxophonist and two very annoyed cats.

Oh, and if you find a short story competition? Enter it. Not because you’ll win, but because you’ll write.

And writing—even with a jazz solo of regret in the background—is still the best part.

Now it’s YOUR turn –Which short story arc stuck with you?

Would love to get your input in the comment box below.

The post Crafting Killer Short Story Arcs. appeared first on Vered Neta.