Speculation on How and Where Dr. Watson Published His Holmes Chronicles, Part One

Though it would be far too dangerous to explain why at this time, I’ve begun to read all of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes adventures: the four short novels and the five collections of tales. I’m reading them in order of publication rather than grapple with reading them chronologically by case (i.e., in the “this case happened before that case and after that case” sequence debated by dedicated Sherlockians such as William Baring-Gould). Attempting to follow the latter, I fear, might lead to madness. After all, Conan Doyle set each adventure whenever he darned well felt like and often with no clear-cut clues of when a story is set.

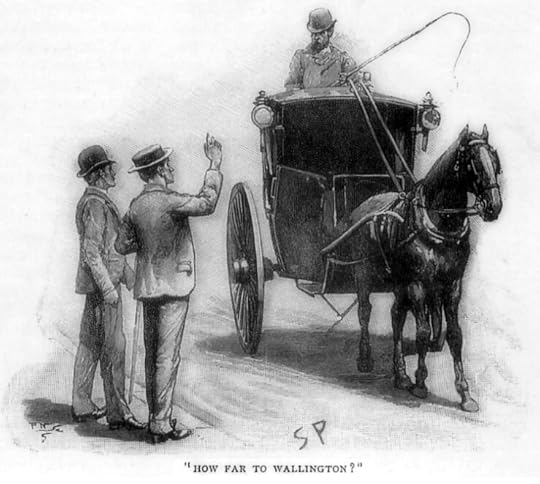

One of Sidney Paget’s wonderful illustrations for the Holmes series. Paget did much to establish how the great detective is visualized by readers and by costumers (though seeing him a boater hat — as he is here — seems not to have taken root).

One of Sidney Paget’s wonderful illustrations for the Holmes series. Paget did much to establish how the great detective is visualized by readers and by costumers (though seeing him a boater hat — as he is here — seems not to have taken root).My main objective in this project is to find evidence of how and where Dr. Watson published his chronicles. Was it in The Strand, where a good many of the stories actually debuted, albeit attributed to the pen of someone named Arthur Conan Doyle? This is how the problem is handled in the well-known TV adaptations starring Jeremy Brett. It’s a fun approach, to be sure, and I do enjoy when the fourth wall is, at least, bumped.

However, I’m fairly certain The Strand Magazine is never alluded to in the tales themselves. I want to see what those texts really do suggest and compare that to what was available in the late-Victorian and early-Edwardian eras, specifically publications likely to print a non-fiction narrative of a private investigator’s methods. It’s all fanciful speculation, of course, but hopefully there might be a point or two of interest in the endeavor.

So far, I’ve read A Study in Scarlet (1887), The Sign of [the] Four (1890), and The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. (1891-1892). Here’s the very first reference I’ve found to Watson recording — and making public — Holmes’s remarkable skill at solving a mystery.

A Study in Scarlet:

Watson [to Holmes]: “Your merits should be publicly recognised. You should publish an account of the case. If you won’t, I will for you.”

Watson: “I have all the facts in my journal, and the public shall know about them.”

There’s not much to go on here, but we see that the doctor intends to become Holmes’s biographer and, in a way, his publicist right from start. Better evidence in found in the next work.

The Sign of the Four:

Watson [referring to the previous case]: “I was never so struck by anything in my life. I even embodied it in a small brochure, with the somewhat fantastic title of ‘A Study in Scarlet.'”

Watson [after Holmes complains of the romantic elements he included]: “I was annoyed at this criticism of a work which had been specially designed to please him. I confess, too, that I was irritated by the egotism which seemed to demand that every line of my pamphlet should be devoted to his own special doings.”

Holmes [on why he must disguise himself at times]: “You see, a good many of the criminal classes begin to know me — especially since our friend here took to publishing some of my cases.”

Ah ha! Watson published that first case as a pamphlet! I’ve run into 19th-century pamphlets fairly often. (There are several ghost-related ones included under “Pamphlets on Individual, Purportedly True Hauntings” on my page titled The Victorian Ghost Hunter’s Library.) As explained on the 19th Century British Pamphlets Online site, these relatively short publications were printed in limited numbers, yet served as “a significant form of publication in the 19th Century and they can complement other publications such as books, newspapers and periodicals.” While pamphlets addressed a wide variety of topics, it’s interesting that they seem to have been a reliable means to share medical discoveries. Watson, then, would have been familiar with pamphlet publication.

I hope to research true-crime pamphlets further, but for now, one might glance over Waldemar Fitzroy Peacock’s 22-page “Who Committed the Great Coram-Street Murder? An Original Investigation” to glean what Watson’s pamphlet might’ve looked like.

Hold on! Why does Holmes say that Watson has taken “to publishing some of my cases”? Some? At this point, one would think that the doctor has only published A Study in Scarlet. I have no answer, and it joins several stumpers I’ve hit during this first chunk of reading. Can we safely assume that the police inspector Athelney Jones in A Sign of the Four reappears as the police inspector Peter Jones in “The Red-Headed League”? Why is the landlady named “Mrs. Turner” in “A Scandal in Bohemia,” not the “Mrs. Hudson” named previously in The Sign of the Four and afterward in “The Five Orange Pips”? Why is John H. Watson called “James” by his wife in “The Man with the Twisted Lip”? These mini-mysteries have probably been addressed elsewhere by those smarter than me. I must remain focused on the task at hand!

The endlessly fascinating Arthur Conan Doyle

The endlessly fascinating Arthur Conan DoyleWhile pamphlet publication accounts nicely for A Study in Scarlet and The Sign of the Four, it feels doubtful that Watson would publish the many shorter narratives to follow in the same way. Even though pamphlets could be very short, I’ve found no evidence that they accommodated a significant series. That’s monthly magazine or possibly book territory. Let’s turn to those shorter chronicles.

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

“A Scandal in Bohemia”

Holmes [to Watson]: “By the way, since you are interested in these little problems, and since you are good enough to chronicle one or two of my trifling experiences, you may be interested in this.”

Watson: “I was already deeply interested in his inquiry, for, though it was surrounded by none of the grim and strange features which were associated with the two crimes which I had elsewhere recorded, still, the nature of the case and the exalted station of his client gave it a character of its own.

“The Red-Headed League”

Holmes: “I know, my dear Watson, that you share my love of all that is bizarre and outside the conventions and humdrum routine of everyday life. You have shown your relish for it by the enthusiasm which has prompted you to chronicle, and, if you will excuse my saying so, somewhat to embellish so many of my own little adventures.”

“A Case of Identity”

Holmes [to Watson, regarding a delicate case]: “I cannot confide it even to you, who have been good enough to chronicle one or two of my problems.”

“The Five Orange Pips”

Watson: “When I glance over my notes and records of the Sherlock Holmes cases between the years 1882 and 1890, I am faced by so many which present strange and interesting features that it is no easy matter to know which to choose and which to leave. … There is, however, one of these which is so remarkable in its details and so startling in its results that I am tempted to give some account of it in spite of the fact that there are points in connection with it which never have, and probably never will be, entirely cleared up.”

“The Speckled Band”

Watson: “The events in question occurred in the early days of my association with Holmes, when we were sharing rooms as bachelors in Baker Street. It is possible that I might have placed them upon record before, but a promise of secrecy was made at the time, from which I have only been freed during the last month by the untimely death of the lady to whom the pledge was given. It is perhaps as well that the facts should now come to light, for I have reasons to know that there are widespread rumours as to the death of Dr. Grimesby Roylott which tend to make the matter even more terrible than the truth.”

“The Engineer’s Thumb”

Watson [contrasting this case to another]: “[T]he other was so strange in its inception and so dramatic in its details that it may be the more worthy of being placed upon record, even if it gave my friend fewer openings for those deductive methods of reasoning by which he achieved such remarkable results. The story has, I believe, been told more than once in the newspapers, but, like all such narratives, its effect is much less striking when set forth en bloc in a single half-column of print than when the facts slowly evolve before your own eyes, and the mystery clears gradually away as each new discovery furnishes a step which leads on to the complete truth.”

“The Noble Bachelor”

Watson: “As I have reason to believe, however, that the full facts have never been revealed to the general public, and as my friend Sherlock Holmes had a considerable share in clearing the matter up, I feel that no memoir of him would be complete without some little sketch of this remarkable episode.”

“The Copper Beeches”

Holmes [regarding how the “least important and lowliest manifestations” of art can sometimes be its “keenest pleasure”]: “It is pleasant to me to observe, Watson, that you have so far grasped this truth that in these little records of our cases which you have been good enough to draw up, and, I am bound to say, occasionally to embellish, you have given prominence not so much to the many causes célèbres and sensational trials in which I have figured but rather to those incidents which may have been trivial in themselves, but which have given room for those faculties of deduction and of logical synthesis which I have made my special province.”

Watson: “And yet … I cannot quite hold myself absolved from the charge of sensationalism which has been urged against my records.”

Holmes: “[Y]ou have erred perhaps in attempting to put colour and life into each of your statements instead of confining yourself to the task of placing upon record that severe reasoning from cause to effect which is really the only notable feature about the thing. … You have degraded what should have been a course of lectures into a series of tales. … [Y]ou can hardly be open to a charge of sensationalism, … [b]ut in avoiding the sensational, I fear that you may have bordered on the trivial.”

Watson: “The end may have been so, … but the methods I hold to have been novel and of interest.

Holmes: “Pshaw, my dear fellow, what do the public, the great unobservant public, who could hardly tell a weaver by his tooth or a compositor by his left thumb, care about the finer shades of analysis and deduction!”

These exchanges give some insight into Watson’s goals for penning the investigations and Holmes’s disapproval of how his friend handled them. Holmes wants them to be more about logical deduction; Watson contends the events demand a more rounded approach, one encompassing the stuff of life. Great characterization here, but little about the “how and where” of publishing the narratives.

Maybe there are some clues in the word choices: chronicle, account, record, and even statement. There’s also a contrast between what Waston is writing and what’s found in newspapers. Still, as implied in the phrase “the great unobservant public,” Watson is presenting his narratives to a wide readership. He remains Holmes’s publicist.

In terms of specific journals, let’s start with suspects bearing some basic resemblance to The National Police Gazette. Despite the title, this journal was aimed at male readers of all walks of life rather than those in law enforcement. But it was American, not British. And it was decidedly sensational, which perhaps relates to Holmes and Watson’s concern for how much sensationalism was added. I’ll continue to look into this possibility of a non-fiction journal that specialized in crime fighting.

For now, it might be just as likely that Watson sought more general magazines. Indeed, it wasn’t unusual for true-crime articles to be found in these broad-appeal journals, some of which are listed here and here. Conan Doyle himself wrote a three-part series of “studies of the actual history of crime” — found here, here, and here — for none other than The Strand. So, yeah, I’m back to the same magazine where most of the Holmes tales were published.

But this investigation has just begun. I’ll have more to say when I’ve read more of Watson’s published records, accounts, chronicles….

— Tim