Characters of "Cold Victory " - Wing Commander Robin Priestman

Cold Victory has a large and diverse cast. There is no one character who dominates the book and deserves the title of "main protagonist." Nevertheless, as the senior officer at RAF Gatow -- at this time in history the business airfield in the entire world -- Robin does take precedence of the others. Besides, he's was the hero of "Where Eagles Never Flew" and is familiar to my loyal readers as a Battle of Britain ace and squadron leader.

This excerpt is the first scene in which Robin appears in Cold Victory and highlights the situation he finds himself in at the the start of the book.

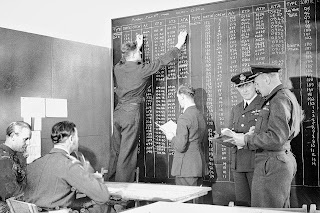

The drizzling rain from the low overcast sky suited WingCommander Robin Priestman’s mood. Although somewhat better than the dense fogof the previous few days, the ceiling was still too low to allow a return tofull operations. The tower was landing aircraft with ground-controlled approach(GCA) once every five instead of once every three minutes, and due to worseweather at the departure fields, there were intermittent gaps in the incomingtraffic.

Hearing the silence, Robin left his desk and went to gaze intothe gloom. Spread out directly before his window were the hangars andhardstandings where the aircraft off-loaded inbound cargoes and a couple of thecivilian charter aircraft loaded outbound cargoes. Further in the distance werethe parallel runways, one surfaced with pierced-steel-plate or PSP for take-offsand one made of concrete and surfaced with tarmac for landings. Roughly twodozen Yorks were being off-loaded just below his window, while a squadron ofDakotas was drawn up beyond the farthest runway preparing to embark childrenbound for the West. But no aircraft were moving.

Robin sighed. He was no longer the station commander, merelythe “acting station commander” until his replacement arrived. He could notallow that subtle change to alter his efficiency or his outward appearance andbehaviour. He had been careful to arrive sharply at 7:30 am as usual. He haddressed in his best blues with his shoes polished to a shine and the creases ofhis trousers smartly pressed. He attempted to look and sound cheerful wheneverhe interacted with other personnel.

In the privacy of his office, however, it was hard to maintainthat façade of normality. Although he had accepted the assignment to Berlinreluctantly, in the eleven months since his arrival, his lingering wartimehostility toward the Germans had melted away. In its place, first mistrust andthen gradually hatred of the Russians had taken root. He had come to see Stalinas every bit as bad as Hitler — if not worse. Stalin had institutionalisedinhumanity and was actively trying to spread his reign of terror to the wholeof Germany and ultimately the rest of Europe. He had to be stopped. As aresult, with each day of the Airlift, Robin’s commitment to aiding the besiegedBerliners had grown. It had long since reached the point where his work herewas not a job but a mission. Only, as of Sunday, it was not his missionany more.

There was a knock on the door, and he called “Come in” overhis shoulder. Flight Lieutenant Boyd, the intelligence officer, entered. “I’vegot today’s papers for you, sir.”

Robin returned to his desk but remained standing as Boydspread the press clippings out in front of him. Most of the headlines declared“SED Putsch!” or “Attempted Communist Coup!” He also noticed an articleheaded with the words: “Mayor Reuter requests Allied protection.” According tothe translations tacked to the Soviet-controlled newspapers, the tone in theEastern media was triumphant: “Workers and Farmers End Tyrannical Government,”“Capitalist Puppets Thrown Out!” “Democratically Elected Council Boots OutReuter Terror-Clique!”

“I’d like to draw your attention to the following item,” Boydcontinued his briefing by pointing to one of the clippings. “In this article,the Soviet Military Administration promises to increase coal rations and toprovide 250 grams of chocolate per household per month to those registered inthe East.”

Robin snorted, then with a glance at his intelligence officer,he asked, “Do you think many West Berliners will take the bait and register inthe East for the sake of a little more coal?”

“It’s hard to know,” Boyd admitted. “Everyone I’ve been ableto talk to scoffs at the idea — pointing out that it highlights Sovietstinginess and contempt. But it’s the people I can’t talk to who may beinclined to take up the offer.”

“Not that it hurts us in any way,” Robin reflected. “The morecoal the Berliners get from the Soviets, the less we need to fly in. As for thechocolate….” He shrugged. “Why would any child want Russian chocolate whenAmerican chocolate rains down on them from the skies?”

“My view exactly. You may be more interested in this piece.”Boyd indicated an article he had circled. “The SED’s counter-mayor has promisedto give workers a 30% pay rise while declaring his intention to expropriate allfactories and businesses employing more than five people.”

“At least he’s honest and open about it. Anything else I needto know?”

“Not just now, sir,” Boyd replied. Robin thanked him and theflight lieutenant withdrew.

Before Robin could settle into his work, however, there wasanother knock. This time the head that looked in was that of Lt. Colonel GrahamRussell of the Corps of Royal Engineers. Graham was not his subordinate; he wasa friend.

“Got a minute, Robin?” Graham asked.

“For you, yes,” Robin answered.

Graham closed the door behind him and advanced across the roomto stand just in front of Robin’s desk. “I had to talk to you because I’veheard a terrible rumour at Army HQ.”

Robin raised his eyebrows.

“Herbert made an off-hand remark that you were on our way out.Surely that isn’t true?”

“Unfortunately, yes.”

“But why?” Graham sounded stunned.

“Because I went ahead with the evacuation of the children andother vulnerable citizens without clearing it through Group Captain Bagshot.”

“But the Berlin City Government requested theevacuations?”

“Correct.”

“I must be missing something,” Graham admitted and looked atRobin expectantly.

“General Herbert is Commandant of the British Sector ofBerlin. He has no authority over the Airlift. He asked General Tunner to handlethe evacuations and Tunner said ‘no,’ but gave explicit permission for the RAFto do whatever it liked. Herbert asked me for RAF action, bypassing Bagshot,and I agreed without clearing it. Bagshot, unsurprisingly, was livid about mybreach of military protocol and sacked me on the spot.”

“Did he order the evacuations halted?”

“Even he recognised that I’d made that impossible by mypromise to the City Council and by starting the evacuations on a large scalebefore running cameras. Which is why, no doubt, he was so determined to have myhead.”

“I can’t say how sorry I am about this. Your friendship,Emily’s hospitality — it has meant the world to me,” Graham stammered out. [...] "I can’t believe you’re being cashiered for doing whatGeneral Herbert asked you to do. Does this mean you could face additionalunpleasantness?”

Robin drew a deep breath, “It could. The Air Ministry doesn’tlike ‘insubordinate officers’ and I may be handed a bowler hat instead of a newassignment.” Robin tried to keep his voice as neutral as possible, but Grahamsaw through him. They were alike in this; the service was their life.

Graham asked in a low voice, “Do you regret it, Robin?”

“Not for a moment. Look out there, Graham.” He pointed towardthe row of Dakotas and the dilapidated Berlin buses disgorging children besidethem. “Every child that gets out of Berlin today is one who will not besubject to Stalin’s terror tomorrow. Every child boarding those Daks will havea chance to grow up without the fear of famine or arrest or a trip to theGulag.”

Graham nodded grimly. Eleven days in Soviet detention hadconvinced him that the worst rumours of brainwashing, slave labour and massmurders were true. Graham had learned to fear the Russian bear.

Robin was watching the invariably chaotic embarkation of thechildren. Despite efforts by teachers and parents to keep the kids quiet andstill, they were too excited to do as they were told. Even from this distance,Robin could see children drifting off to look at the planes and saw franticadults trying to herd them back to the side as a Lancastrian tanker on approachfell out of the cloud and plonked down hard on the runway.

“Do you think the kids appreciate what we’re doing for them?”Graham asked from behind him.

“They understand, Graham,” Robin answered seriously, “theyunderstand more profoundly than you could imagine.” He turned to look back atGraham and asked, “Haven’t you noticed anything unusual on my desk?”

Graham looked blank and then directed his attention to theStation Commander’s desk. It took him a moment before he exclaimed, “The TeddyBear!”

Robin reached over and took the ragged, threadbare andlopsided stuffed animal from his desk. He looked down into the beady eyes ofthe toy for a few moments before turning it around and holding it up to faceGraham. “Meet Bertie the Bear, a wise veteran of — I’m told — 62 air raids,including one that destroyed the house in which he lived. Bertie, his friendLiesl explained, kept his beloved friend safe day and night, even when theIvans broke into her apartment and did terrible things to her mummy. Bertie,she said, was the only thing of any value that she could give to me. I tried toconvince her that he wanted to stay with her, but she said ‘no.’ She said, ‘Youare keeping us safe from the Ivans. I want Bertie to help you, so you can makesure my mummy will not be hurt like that ever again.’”

In the silence following his words, the sound of the rainseemed stronger.

“If I were still station commander, Graham, I would askpermission to increase, not reduce, these evacuations. I would seek to get notjust the children and chronically ill people out of Berlin, but the singlemothers and some of the youths as well. Did you know the Boy Scouts have askedpermission to help off-load the aircraft? Not one of them weighs what theyshould at their age, but they insisted they could double up to carry ten-poundsacks of coal!”

Graham nodded understanding, and Robin concluded with adefeated shrug, “But I am no longer station commander, and God knows how mysuccessor will feel about the evacuations — or the Berliners themselves.”

Find out more about the Bridge to Tomorrow series, the awards it has won, and read reviews at: https://helenapschrader.net/bridge-to-tomorrow/