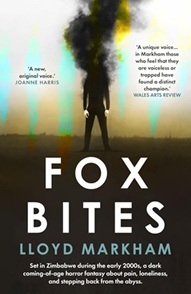

Review of Fox Bites, by Lloyd Markham, pub. Parthian 2024

As he gets into the passenger seat, Taban wonders if the story he told Eve is the grimmest she can imagine. Because it isn’t for him. For him the tree’s deformed growth being the result of an unstoppable external force is the happiest plausible explanation. There is another possible version of the tree’s story, which is far more painful to him. In it everything is the same, but there is no lightning to blame. The tree is simply born a twisted mutant.

Well, this is as intense and complex a novel as I’ve read for a while. It has three constantly interwoven strands: first, and most important, what goes on in the life and the head of a boy called Taban, second, politics in Zimbabwe and third, a fantasy strand based loosely on a lot of different mythologies and involving foxes. I‘m not sure quite what it is that attracts poets and novelists to mythical foxes with superpowers; apart from Ted Hughes, there is the Japanese kitsune, which seems to crop up quite often, and Metin Murat’s recent novel The Crescent Moon Fox (Armida, 2022) featured a similar beast.

Markham grew up in Zimbabwe and is thus able to convey a sense of the novel’s place without particularly trying to. There are no passages of conscious topographical description; just the odd mention, in passing, of avenues of jacaranda trees and the need to watch out for crocodiles near the water is enough to remind us where we are.

Taban, small, shy and something of a misfit, sees himself as a victim – he does get bullied, but it is never clear quite how much, because although he is the point-of-view character through whose eyes we see, he is also unreliable. Like most children with a grudge against their world, he fantasises becoming strong enough to take revenge on it and sometimes seems able to do so by sheer force of will. He also has an (adult) alter ego, Solomon Mushonga, from the novel’s “political” strand, who expresses all the latent ruthlessness and potential cruelty of which few would think Taban capable. I may say here that I find this political strand utterly fascinating: there is a scene of an election debate on land reform in a postcolonial situation that is brilliantly done and maintains its audience’s interest in a way you might not think such a fictional scene could do.

Then there is the fantasy strand. I would guess some readers will be leery of this and try to rationalise it. It is certainly possible, for instance, to see the terrible mound of bones Taban and Hilde climb as a reference to political wars:

"The whole top layer of the mound starts sliding. Hilde snatches Taban’s arm to stop him sliding with it. As it peels away, sloughing to the street below, more bones reveal themselves. Hundreds if not thousands. Femurs and clavicles and tibias and sternums and even whole spinal columns. All knotted together like the tails of a rat king. They are different sizes and vary in colour and condition, but they all have one thing in common – they’re from humans."

And the fox-bites which appear only to Taban and his mother are clearly at least in part products of their own minds, the consequence of troubled and guilt-ridden childhoods. Nevertheless, the mythological/fantasy elements can’t be totally reasoned away and must to a degree be accepted. I didn’t have a problem with this, though it wasn’t the element of the novel that most gripped me (and I did feel the magic dagger could maybe have been better seeded; it seems to crop up when there’s suddenly a use for it).

What I found most memorable was Markham’s ability to clinch some concept that matters in a few words. Solomon’s chilling response, when a soldier tells him there is no evidence of a conspiracy: “Lieutenant, I told you to find evidence. Not look for evidence”. And Taban’s moment of self-realisation; “The reason the other students laugh when he gets beaten up is because of what he is. Not what is being done to him.”

Taban’s friend Hilde says at one point, “I’ve always been unhappy – feeling like I was from two places at once”. In some ways this is true of their whole community; born in Zimbabwe, Taban is of European descent and not wholly at home in his birth country, though neither does he identify with the despised “Albions” who used to own it. “Discovering? Really? How can you discover somewhere already home to over a million people? Discovery? Albions have a thousand euphemisms for conquest. Perhaps that is where their language’s nuance lies?”. It is made clear, in fact, that the “Albions” have consistently misunderstood the country from the start; they have made fatally important mistranslations, and Taban’s own name is a mishearing by his parents of the Setswana name “Thabang”. It means “be happy”, ironically enough, since this is something Taban finds elusive. When he is on his way, at the novel’s end, to the UK in a plane, the continuing presence of the fox suggests that you cannot emigrate from what you are.

.