Teaching Krazy Kat in a Modernist Poetry Course

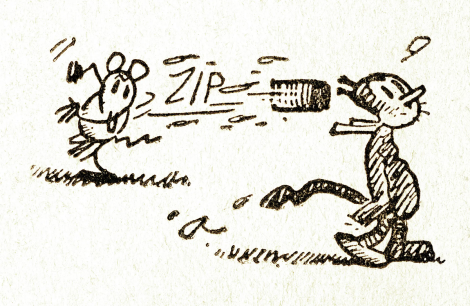

The above strip was first published on January 6, 1918, and I placed it first in the selection of Krazy Kat dailies I assigned to Professor Lesley Wheeler’s Modern Poetry students earlier this spring. George Herriman doesn’t usually share syllabus space with T.S. Eliot, H.D., and Langston Hughes, but there are good reasons why he should.

I was subbing for a day because Lesley was at the AWP conference, but she’s taught Herriman’s Krazy Kat in previous iterations of the course too. Her ENGL 363 is continuously evolving, and this semester it was titled “Modern Poetry’s Media.” The comics medium isn’t a typical home for poetry, but Herriman’s verbal and visual experimentation offers an exception.

The homework reading included: Gabrielle Bellot’s “The Gender Fluidity of Krazy Kat” (New Yorker, January 19, 2017), and “Seth on Peanuts: Comics = Poetry + Graphic Design” (which excerpts passages from a 2006 interview in Carousel magazine). I culled fifteen Krazy Kate dailies from online archives (The Comic Strip Library is particularly useful), leaning more heavily on poetic allusions than I would when teaching Herriman in a comics course.

I’ll post my selection first, then my lesson plan below:

September, 1918

April 30, 1919

February 19, 1919

January 21, 1919

January 23, 1919

June 10, 1919

May 8, 1919

February 20, 1919

May 13, 1919

May 3, 1919

December 18, 1918

December 12, 1918

October 26, 1918

April 1, 1919

I also included five Sunday comics from the same 1918-1919 span:

This last one keeps Krazy Kat in its natural habitat, showing how the comic first appeared on a newspaper page:

As usual, my plan changed as soon as I entered the room. I asked everyone in the semi-circle of twenty students to introduce themselves and name one thing that personally interested them from the readings. That always takes more time than I expect (about ten minutes this time), but the brief back-and-forths are worth it, getting everyone’s voice heard and laying all kinds of helpful groundwork.

The students placed a couple of key biographical facts from the Bellot article front-and-center. One mentioned Herriman’s race. Bellot writes:

“Herriman was born in New Orleans, in 1880, to a mixed-race family; his great-grandfather, Stephen Herriman, was a white New Yorker who had children with a “free woman of color,” Justine Olivier, in what was then a common social arrangement in New Orleans called plaçage. George Herriman was one of the class of Louisianans known as blanc fo’cé: Creoles who actively tried to pass as white.”

The detail made the student go back and reread the “invisible in front of a black sheet” in new light (the Sunday strip is my personal favorite and grew into a section in the first chapter of my forthcoming The Color of Paper.)

Another student brought up Krazy Kat’s gender identity. Again, from Bellot:

“In an era when books depicting homosexuality and gender nonconformity could lead to charges of obscenity,“Krazy Kat,” Tisserand notes, featured a gender-shifting protagonist who was in love with a male character. Herriman would switch the cat’s pronouns, so Krazy’s gender, to the consternation of many readers, was never stable.”

Bellot published the article in 2017, and asking “what ‘Krazy Kat’ means at the dawning of a Donald Trump Administration,” a statement that resonates again at the dawning of a second Donald Trump administration. I also pointed attention to Bellot’s statement: “Reading ‘Krazy Kat’ in light of Herriman’s silent struggles with his identity layers a soft poignancy over its stories of a cat, a dog, and a mouse. As a trans woman who, like Herriman, is multiracial, the strip spoke to me in unexpected ways.”

There were plenty of other comments too, including (my favorite) how Herriman’s use of meta makes Krazy Kat feel especially modernist.

With a wide range of reactions fully voiced, we delved deeper into the comics. I “started” my lesson plan by dividing the room into pairs, assigning them the first ten strips to perform aloud as dialogues, including sound effects. I initially asked them to stand up, but reading from laptops proved clunky. One pair did construct a paper brick to “zip.” In addition to being really fun, the micro-performances voice Herriman’s language (which is often written in a kind of semi-phonetic dialect), including the back-and-forth rhythms.

We discussed what we heard a bit, and then I asked all of the Ignatz readers to raise their hands, then all the Krazy readers to raise theirs, telling each set to list their character’s key traits. We moved around the circle twice, hearing points of agreement, disagreement, and variations between. Personally, I’d never considered the Ignatz-Krazy dynamic in terms of older-younger siblings, and both characters were described as being both smarter and less smart than the other — which opened discussion into the contrasting ways each has their own kinds of authority.

A couple of students included visual qualities in their descriptions, which transitioned to my asking everyone to draw their character. After a minute or two, each shared their drawing with the students on either side of them, and we discussed details. Krazy’s tail provided the longest analysis — how Herriman sometimes renders it in a Z shape, and what that graphic quality means within each strip and overall.

Students were already describing the rhythmic role of panels, which segued to Seth likening comic strips to haikus — though I said quatrains may be a better parallel for four-panel strips. I mentioned that “stanza” means “room” in Italian (alas, no Italian speakers were present to draw out that fact), which is similar to the function of the panel. I asked everyone to pick a favorite passage from Seth’s article, write something down about it, then talk to their partner, before opening discussion to the whole room. I also wrote “Doot-doot-doot Doot” on the board, the rhythm Seth identifies for Peanuts strips. I thought we would get to the rhythmic differences between Herriman’s three- , four-, and five-panel strips, but it didn’t come up organically, and I wanted to explore some of the Sunday comics before the hour ended.

So reusing the Ignatz/Krazy division, I asked half the class to list ways the Sunday comics are similar to the dailies, with specific examples, and the other half to list ways the Sunday comics and the dialies differ, also with specifics. Many smart things emerged in the final ten minutes, including how the Sundays feature a narrator who combines qualities of Herriman-like omniscience with character-like narrative involvement. The Sundays are also like free verse compared to the rigid panel structure of the dailies.

More things were said, and many more could have been said, but time ran out. I of course overplanned, so never asked my culminating question: “In one (as long as you like) sentence, what is Krazy Kat about?”

Since Bellot emerged in the opening discussion, I had already jettisoned: “Apply Bellot to the KK selection; link a passage with a specific strip. Explain connection.”

And I never really thought we’d get to my final bit of fun: “Draw a new KK comic strip that illustrates/continues a central element.”

Maybe next year.

Chris Gavaler's Blog

- Chris Gavaler's profile

- 3 followers