Patrick White's Lessons in Ham

This year marks the 121st birthday of Australia’s prodigal son: our best novelist, muckraker, playwright, dog breeder – you name it. I’ll try to avoid sycophancy, but Paddy White was the one who got me started. I read all of his novels and plays before I was twenty-five and, I suppose, his voice still resonates in mine, as it does in that of most Australian writers. White was our original and most unforgiving vivisector, holding a mirror to a country that didn’t want, or see the need, to look. He described himself as a monster, but that was because he could see the flaws in the glass, and was publicly willing to admit to them.

Thanks for reading Datsunland! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

More than ever, this country needs a White. In a 1988 speech at Melbourne’s La Trobe University, he claimed that most Australian adults ‘remain children at heart’. He called them kidults. He said, ‘That’s why they’re so easily deceived by politicians, developers, organisers of festivals …’ And here’s the essence of why so many Australians have a problem with White: he sailed closer to the truth than anyone. He described an Australia that, for better or worse, still exists. ‘Australians have suffered in the past, which they tend to forget now that they’re on with the bonfires – the champagne (the ad man’s magic lure) and the festivals.’

White was constantly reminding us that we’re only as good as our worst off. ‘Aborigines may not be shot and poisoned as they were in the early days of colonisation, but there are subtler ways of disposing of them.’

For such an English Australian, he hated our subservience. ‘The Royal Goons will be with us most of the year [1988]. Queen Betty England is invited to open the ‘concept’ of Darling Harbour, and she and her bully boy will be at the inflated/ruinous Parliament House.’

Patrick White was born on 28 May 1912. Although his family were from the Upper Hunter Region (including his domineering mother, Ruth, who became Elizabeth Hunter in The Eye of the Storm), White’s family were in London when he was born. So much of how he wrote, and thought, came from a European perspective, but White’s greatest achievement was to tailor this view to an Australian landscape: Voss, trudging across the interior, ‘talking’ to his love, Laura Trevelyan; Ellen Roxburgh, with her fringe of leaves, and the escaped convict, Jack Chance, waking the sands of Fraser Island; and perhaps the best of all, for me, the Aboriginal artist, Alf Dubbo, and Holocaust survivor, Mordecai Himmelfarb, inhabiting the alleyways and factory yards of White’s mythical Sarsaparilla, riding their chariot towards salvation.

White was back in Australia as a six-month-old, becoming hard-wired to the sounds and smells of his native city on the harbour. At thirteen, he returned to England for secondary schooling at Cheltenham College, Gloucestershire, a period he later described as a ‘four year prison sentence’. He persuaded his parents to let him return to Australia where he spent two years working as a stockman at Bolaro, near the Snowy Mountains. But then he was back in England to study a BA at Cambridge, a period that resulted in his first novel, Happy Valley. This constant to-and-fro created a man who was part Rilke, part sheep-dip, part Camus, part Australian Suburban, bitches on heat, and backyard abortions. White’s enormous intellect, ear for dialogue, eye for character, would settle uneasily in 1950s Australia, after he returned to live in Sydney in 1948 with his partner Manoly Lascaris.

White’s connections with Adelaide, and South Australia, are many and varied. He was (almost) life-long friends with local author and historian Geoffrey Dutton and his wife, Nin (before the inevitable falling-out that befell most of White’s acquaintances). Like White, Dutton was born into pastoral wealth, this time in the Clare Valley, near Kapunda. ‘Anlaby’ (Australia’s oldest sheep stud) hosted White and Lascaris many times, as did the Dutton’s holiday house on Kangaroo Island. After White’s first visit to the island in 1962, Nin Dutton described how he would take hours cleaning the dishes: ‘All the knives were just so; all the plates rinsed three times.’ He and Lascaris would swim early in the morning and return to the Duttons’ house for a breakfast of fish and eggs. The Duttons forbade him to write on the island, and it’s here we can see a rare glimpse of our only (pre-Coetzee) Nobel Prize Winner for Literature with his guard down, socks off, itching, no doubt, to return to his writing desk in Sydney.

In 1959, White sent Dutton a play he’d written years earlier that had been sitting gathering dust in a drawer. Dutton told White The Ham Funeral should be performed at the Adelaide Festival. He presented the script to the festival’s committee who, at first, were enthusiastic. Artistic Director Professor John Bishop flew to Sydney to discuss the play with White. But, Adelaide being Adelaide, things soon turned pear-shaped for the playwright.

The Australian Ambassador to Washington was encouraging the committee to mount Archibald McLeish’s Broadway show, JB. Several of the governors just didn’t understand what White was on about in the Funeral. Local brewer Rolly Jacobs thought the script filthy (especially when the Young Man finds a foetus in a rubbish bin). Another two governors, Clive and Ewen Waterman (who owned, among other things, the local Mercedes Benz franchise) took advice from Glen McBride (an ex-Tivoli manager) who claimed the play was ‘not up to much’.

The play was then rejected because the governors, apparently, feared a poor box-office.

The committee became split between the pro- and anti-White factions. One pro- governor warned the others to ‘think seriously before turning down the opportunity of a world premiere of a work of this class’. But the nail was put in White’s coffin by an Englishman, Neil Hutchison, who’d been sent by the BBC to Australia to teach us a thing or two about culture (as Director of Drama and Features at the ABC). He told the committee that the Funeral would be ‘very tedious in production. There is practically no character development and the dialogue is insufferably mannered. As for the abortion in the dustbin … Really, words fail me!’

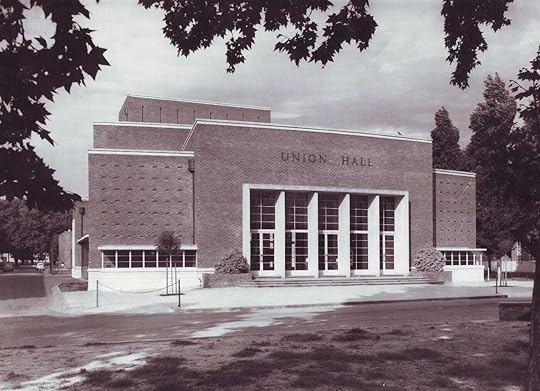

Luckily, Adelaide redeemed itself. The play was given to physicist-thespian Harry Medlin and produced by the Adelaide University Theatre Guild in Union Hall. Dutton and Max Harris got behind Medlin and supported the production. White was given a cheque for 25 pounds, and chose John Tasker to direct. On 15 November 1961, John Adams stepped on-stage as the Young Man. Joan Bruce, Hedley Cullen and Dennis Olsen all played a part in Australian theatrical history, the physical remains of which were lost when Union Hall was removed from the State Heritage Register by the incumbent anti-intellectual, anti-cultural Labor government. The theatre was then demolished in an act of cultural vandalism by the University of Adelaide in November 2010.

The Theatre Guild repeated its success (and affirmed its relationship with White) the following year by producing The Season at Sarsaparilla and, in March 1964, with Night on a Bald Mountain. By this time, the Festival had, according to David Marr, ‘relented sufficiently to list Night on a Bald Mountain among the fringe events of the fortnight.’ White, the Duttons and the Nolans (Sid was in town for a show of his African paintings) gathered at The South Australian Hotel on North Terrace. White stayed away from all writers’ events as they sounded ‘quite pathetic’. He wouldn’t have another play produced in Adelaide until March 1982, when Neil Armfield and the Lighthouse Company presented Signal Driver with a much younger John Wood and Kerry Walker.

It might be worth asking ourselves if all that much has changed since the days of The Ham Funeral and ‘the governors’; whether the Adelaide Festival is really interested in celebrating an indigenous culture, or just importing the best from other places. Are our festivals still chokers with modern equivalents of JB (which premiered in Union Hall on 17 March 1962)? What would White say? In reference to the 1988 Bicentenary celebrations he said: ‘When the tents are taken down, we’ll be left with the dark, the emptiness …’

Dutton and White parted ways in 1980. When White learnt that Dutton had accepted money from Mobil for a book he was writing (Impressions of Singapore, 1981) he told him: ‘Australia disgusts me more and more, but what really shatters me is when those I have loved and respected shed their principles along with the others.’

Dutton didn’t take it lying down. ‘It’s time you recovered your sense of proportion, your sense of humour and most of all your sense of humility…’ He told him to reread King Lear, so perhaps he wouldn’t ‘pontificate about other people’s lives.’

In the end, White set standards that no one (except perhaps Manoly) could reach. His life evolved into a set of theories and ideals that rarely connected with the real world of Australia in the 1970s and 80s. And yet, in the end, this is why we remember him as one of the Great Australians, along with some of his idols such as Chifley and Whitlam. After all, it’s not what one achieves in life, but what one aspires to. And it was this lack of ‘worthwhile’ aspiration that constantly disappointed him.

We still have so much to learn from the Whites of the world. He knew how easily decent people are led. ‘The masters will continue to hoodwink the more innocent by telling them they have the best economy, the tallest tower, the coziest casino, the greatest cricketer or swimmer.’

Sound familiar?

White and the 1973 Nobel Prize for Literature

Thanks for reading Datsunland! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Stephen Orr's Blog

- Stephen Orr's profile

- 31 followers