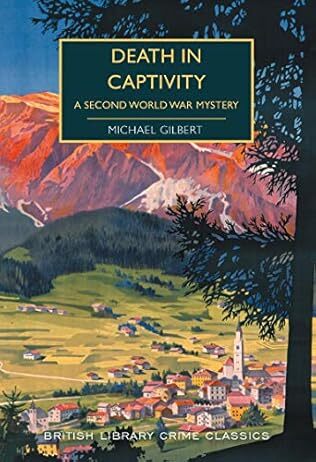

Death In Captivity

A review of Death in Captivity by Michael Gilbert – 250328

Michael Gilbert’s Death in Captivity, also known as The Danger Within, originally published in 1952 and reissued as part of the British Library Crime Classics series, offers a fascinating insight into the life and experiences of prisoners of war of the officer class in the dying days of Fascist Italy during the Second World War. What struck this reader is how relatively liberal and relaxed life in the camp was with the prisoners having time enough to relax, pay games, even prepare to put on a production of The Barretts of Wimpole Street and, of course, plan and execute an escape through tunnelling.

There are, though, some elements of menace, not least the erratic behaviour of the camp commandant, Captain Benucci, concerns as to what will befall the prisoners as the Allied forces advance, and the realization that there is a spy amongst their numbers. The finger of suspicion falls on an unpopular Greek prisoner, Cyriakos Coutoules, who is found dead in one of the escape tunnels so painstakingly excavated. Henry “Cuckoo” Goyles is detailed to investigate what really happened to Coutoules.

Goyles’ task is no easy one with, obviously, no official assistance and in an environment in which everyone seems to know everything but is disinclined to reveal all. In what is part thriller, part locked room murder mystery with a closed circle of suspects, Cuckoo slowly starts to assemble some facts and impressions. Key to what went on was some strange manoeuvres with an ambulance, a wireless playing dance music very loudly, and the sound of an Anglophone voice heard by several witnesses.

The Italians, though, have their own ideas and arrest Roger Byfold, but before they can execute him, news reaches the camp of the fall of Mussolini, signalled by a newly arrived prisoner, Potter, who just as suddenly disappears. By this time the senior group of prisoners are aware that there is more than one informant, suspicions heightened by the unerring ability of the Italian guards to second guess what is going on, the discovery of wires, and a direct reference to a German intelligence officer being in their midst. Goyles, and the reader, had already worked out that Coutoules was just a sideshow.

The rapid turn of events expedites the completion of the tunnelling work and the prisoners break out, Goyles teaming up with Byfold and Tony Long, who had rescued Cuckoo from an earlier tunnel collapse. For a while the narrative concentrates on the trio’s experiences as they make their way through Italy and these passages are vivid, drawing upon Gilbret’s own wartime experiences in the area. The increasingly strained relationships between the three and the uncharacteristic behaviour of two brings the spy issue back into focus.

By this time from an at times bewildering array of characters, Gilbert has narrowed the possible suspects down to just two and, picking his moment to perfection, Goyes reveals the identity of the spy and takes drastic action to ensure his own and that of his innocent companion’s escape from imminent danger.

As a puzzle it is fairly clued and there is more than enough in the narrative for the reader to pick up on the culprit. However, the book is more than a simple whodunit, offering a fascinating insight into conditions in a theatre of war that often gets overlooked. In a series where the definition of classic can seem a little elastic, this is a book that warrants that description.