The Language Of Stamps (2)

During the late 19th century and early 20th systems were developed that imbued the positioning of a postage stamp on a postcard with meaning. Not content with just one stamp some were extended to encompass two.

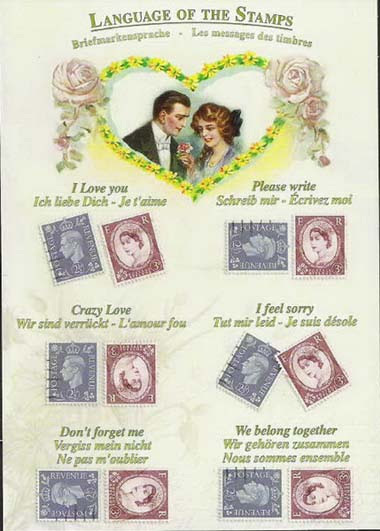

A postcard clearly aimed at English, French, and German speakers revealed the potential offered by two stamps. Two stamps leaning towards the left meant I love you, one at right angles and the other the right way up indicated a desire for a reply, while, touchingly, the two stamps on their sides with the heads away to each other meant don’t forget me and the same arrangement but with the heads pointing towards each other signalled that they belonged together.

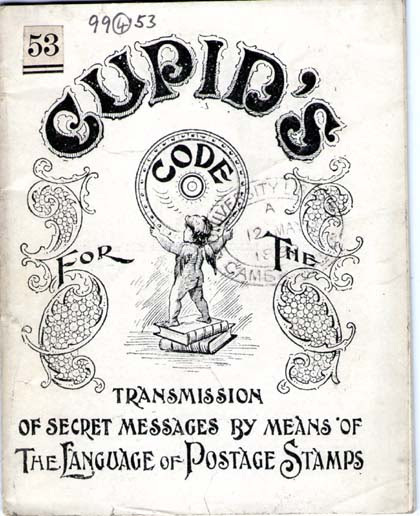

There is always someone, though, who takes matters to extremes. Step forward George Bury who in 1899 devised a code using the position and orientation of stamps. With eight positions and eight orientations, there were sixty-four basic messages, which could be augmented to 128 if two stamps were used. The accompanying pamphlet, Cupid’s Code for the transmission of secret messages by means of the language of postage stamps, included the messages printed in perforated strips and could be re-arranged, giving, he claimed, “close upon 270,000 different ways, so that no attempt to discover any particular combination could possibly succeed”.

Of course, the recipient had to be in on the secret and the pamphlets were sold in pairs. For those who were concerned that even Bury’s complex system did not provide adequate security, he was perfectly willing to sell them, for the princely sum of six shillings, a specially arranged duplicate code, guaranteed to be “non-existent elsewhere”.

It is difficult to get a sense of how widespread the positioning of postage stamps to deliver secret messages really was but there are enough examples from many European countries to suggest that it was an acknowledged, if somewhat niche, practice. A fascinating article in the Western Colorado Beacon Senior News on December 1, 2024, suggests that during the Second World War, when mail was censored, the language of stamps was not only widely known but well-practised. While the US Post Office required the 3-cent stamp to be placed in the right hand corner of the envelope, there was no stipulation as to its orientation.

The article suggest that the favoured system included positioning a stamp upside down at the top left hand corner to signify I love you, a stamp crosswise on the top left corner indicated that the writer’s heart was with another while assent was indicated by a stamp at the top and in the centre of the envelope and a negative response with the stamp occupying a central position at the bottom. Recipients would dread an envelope with a stamp upside down at the top right hand corner which signified write no more and be mortified if the stamp was on the top left corner and at a right angle which indicated the writer’s hatred.

In Russia, where the practice was for a time fashionable, it fell into official disfavour after 1945 not only because of the state’s aversion to any form of secret communication but also because the concept of etiquette was deemed to be bourgeois. In Western Europe there is evidence that the practice lingered well into the 1960s but now is little more than a dimly remembered piece of social history.

The next time I receive an envelope with a postage stamp on it, I will scrutinise its position with care. After all, it might just be trying to tell me something.