The Sensemaker’s Guide to Diagramming & Modeling

When was the last time you felt stuck? Maybe it was a complex project with too many moving parts. Perhaps it was a difficult conversation where words alone weren’t getting your point across. Or maybe it was simply trying to understand something that felt just beyond your grasp.

Whatever it was, I bet a diagram would have helped.

This article covers:

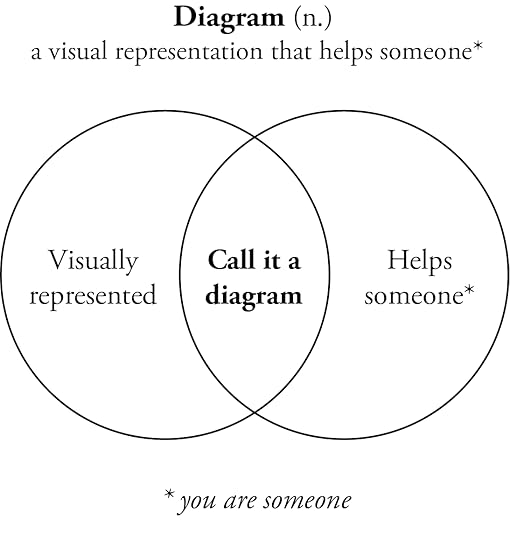

What is Diagramming? What is Modeling?Let’s start with a simple definition:

A diagram is a visual representation that helps someone.

That’s it. If it’s visually represented and it helps someone (even if that someone is just you), congratulations—you’ve made a diagram.

Modeling is creating a representation of something to help us understand it better.

Models don’t have to be visualized to be represented, but when we visualize models, we’re diagramming. For example, writing out the definition of diagram like the above might be the right representation of the model I am trying to teach, but a diagram might help draw the attention of the audience to the two pieces coming together.

The distinction between the two is subtle but important:

Diagramming is about creating a visual artifactModeling is about the thinking process behind itReasons to DiagramWhen we face volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity, diagrams offer us:

Stability in times of volatilityTransparency when facing uncertaintyUnderstanding of complexityClarity through ambiguityKindness to ourselves and othersThat last one might surprise you, but diagrams truly are an act of kindness. They reduce cognitive load and create shared understanding. They give us a place to put our thinking so our brains can rest.

Common Use Cases for DiagrammingPeople diagram for countless reasons, but some common scenarios include:

Explaining complex systems to people who need to understand themFacilitating decision-making by visualizing options and relationshipsPlanning projects by mapping tasks, timelines, and dependenciesAnalyzing problems by breaking them down into manageable piecesCommunicating concepts that are difficult to express in words aloneOrganizing information to reveal patterns and insightsCreating a shared understanding among team members or stakeholdersTypes of ModelsBelow are some of the types of models you are likely to run into in the wild world of sensemaking.

Structural modelA structural model defines the static relationships between entities or components within a system. It answers “What exists and how is it connected?”

These models typically include classes, objects, components, or data structures and their relationships.

Example: Airbnb’s database schema

Airbnb uses a structural model to define how entities like Users, Listings, and Bookings relate.

Process modelA process model illustrates the sequence of activities, decisions, and flows in a system or workflow. It answers “What happens, in what order, and under what conditions?”

Common formats include flowcharts, BPMN diagrams, and swimlane diagrams.

Example: Amazon’s order fulfillment workflow

Amazon uses a Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN) process model to map how an order moves from purchase to delivery:

Behavioral modelA behavioral model represents how a system reacts to internal or external inputs over time. It answers “How does the system behave or respond?”

Often includes state machines, interaction diagrams, or logic models.

Example: Thermostat control logic in Nest

The Nest Thermostat uses a behavioral model to decide when to heat or cool based on sensor input.

Conceptual modelA conceptual model represents how users or stakeholders understand a system or domain. It answers “How do people think this works?”

These are often simplified, abstract representations used to align mental models.

Example: Apple’s Human Interface Guidelines

Apple’s design team maintains a conceptual model of how users understand navigation across iOS apps.

Mathematical modelA mathematical model uses mathematical expressions, algorithms, or statistical methods to simulate real-world phenomena. It answers “What can we calculate, predict, or optimize?”

Includes equations, formulas, and algorithmic logic.

Example: Netflix’s recommendation algorithm

Netflix uses a mathematical model called collaborative filtering.

Types of DiagramsThere are countless types of diagrams out there. A common way to differentiate them is qualitative vs. quantitative. I like to think about types differently. Centering is concentration on a specific point. In my book, Stuck? Diagrams Help. I propose three main centers for diagrams to have.

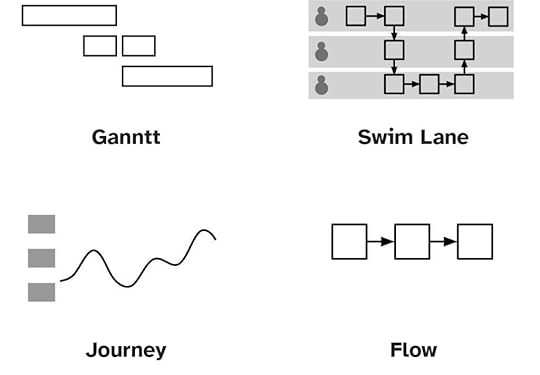

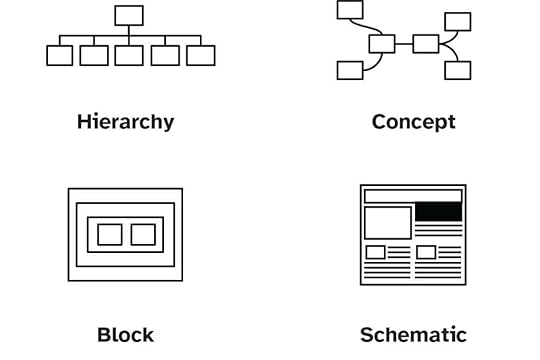

TimeWhen asking questions of when or how, time-based diagrams are helpful.

Examples:

Arrangement

ArrangementWhen asking questions of what or where, arrangement-based diagrams are helpful.

Examples:

Context

ContextWhen asking questions of which or why, context-based diagrams are helpful.

Examples:

As you can see each serves different needs and helps answer different types of questions.

By combining the kind of question you’re centering (Time, Context, Arrangement) with the type of model you’re working with (Structural, Process, Behavioral, Conceptual, or Mathematical), you can find the right kind of diagram to help you.

Here’s a quick cheat sheet:

Diagram x ModelStructuralProcessBehavioralConceptualMathematicalTimeVisual InstructionsGantt ChartTimelineFlow ChartDecision DiagramContextConcept MapJourney MapMental Model DiagramVenn DiagramScatter PlotArrangementSitemapSwim Lane DiagramBlock DiagramQuadrant DiagramBlueprintsApproaching Modeling & DiagrammingEffective modeling involves a thoughtful process:

Set an intention: What do you want this model to accomplish?Research your audience: Who needs to understand this? What do they know already?Choose your scope: What’s included and what’s excluded?Determine scale: How big is the space, and how detailed does this need to be?Iterate and refine: Diagrams are never perfect on the first tryRemember that diagramming is exploratory. You’re trying to make sense of something, so be prepared for your understanding to evolve as you work.

Tips to Getting StartedStart simple: Use basic shapes and lines. Rectangles, circles, and straight lines will get you far.Use a grid: Aligning elements creates visual order that reduces cognitive load.Be consistent: Use the same visual language throughout (don’t mix metaphors).Label everything: Clear labels prevent confusion and questions.Test with others: The only way to know if your diagram helps someone is to test it.Embrace iteration: Your first attempt won’t be perfect, and that’s okay.Don’t overdo it: When it comes to colors, shapes, and decorative elements, less is often more.Hot TakesHere are some opinions I’ve formed over years of diagramming:

There is no such thing as a bad diagram if it helps someone. What matters is effectiveness, not aesthetics.Diagrams made for yourself can look messier than those made for others. Different audiences have different needs.Fancy tools aren’t necessary. Some of the most effective diagrams I’ve made were drawn on napkins or whiteboards.Color-coding should always have a backup. Not everyone perceives color the same way, so don’t rely solely on color to convey meaning.Labels should be as concise as possible. Aim for under 25 characters for most labels.Line crossing is usually avoidable. If your lines need to cross frequently, reconsider your layout.Diagrams can reveal insights that text alone cannot. The act of visualizing information often leads to new understanding.Frequently Asked QuestionsDo I need to be good at drawing to make diagrams?Absolutely not! Diagrams are about clarity, not artistic skill. Simple shapes and lines are all you need.

What’s the best software for diagramming?The one you’re comfortable with. For beginners, I recommend whatever tools you already know—PowerPoint, Google Slides, or even pen and paper work great. As you advance, you might explore dedicated tools.

How do I know if my diagram is good?If it helps someone understand something, it’s a good diagram. Test it with your intended audience and iterate based on their feedback.

What if my diagram gets too complex?That’s a sign you might need multiple diagrams or a different approach. Consider breaking it down into smaller, more focused diagrams.

How much information should I include?Include only what’s necessary to meet your intention. When in doubt, start with less—you can always add more if needed.

Should I make my diagram pretty?Focus on clarity first. Visual appeal can enhance a diagram but should never come at the expense of understanding.

If you want to learn more about my approach to diagramming and modeling, consider attending my workshop on May 16 from 12 PM to 2 PM ET. Blueprint Basics: Making Models That Actually Help — this workshop is free to premium members of the Sensemakers Club along with a new workshop each month. Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for our focus area in June – Controlling Vocabularies

The post The Sensemaker’s Guide to Diagramming & Modeling appeared first on Abby Covert, Information Architect.

Abby Covert's Blog

- Abby Covert's profile

- 41 followers