The 2006 bomb blasts on the Railway network in Mumbai: A Flashback

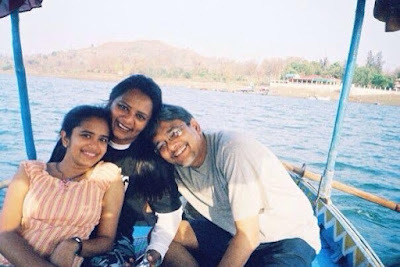

Captions: The bomb blast on the railway network at Mumbai in 2006. Meeta (centre) with her daughter Esha and husband Tushit

Captions: The bomb blast on the railway network at Mumbai in 2006. Meeta (centre) with her daughter Esha and husband Tushit Afew days ago, I had put a review of a Subhash Ghai book on LinkedIn. MeetaTushit Shah, an ExSenior Psychologist at the Narsee Monjee Institute of ManagementStudies, Mumbai, said, ‘Sowell explained and expressed. Shall surely read the book.’

· When I expressed mythanks, Meeta, in a message said, ‘I won’t everforget how you covered our story in 2006. Thank you.’

SoI went to my blog, Shevlin’s World, to read the story again.

Thiswas published in the July 16, 2006 issue of the Hindustan Times, Mumbai.

“Mylife has been shattered”

Studentcounsellor Meeta Shah struggles to cope with the brutal death of her husband

By Shevlin Sebastian

In the drawing room of the sixth floor flat ofMeeta Shah, 44, at Dahisar, there are quite a few people, mostly women. Meetais sitting on a dhurrie, beside a low windowsill, which has a garlandedportrait of her late husband Tushit, 44.

Meeta’sbody is stiff with sorrow and her eyes have become red from too much crying.She sees me at the door and beckons with her hand. But in front of so manywomen, I prefer to stay where I am. Then one by one, they hug her, thesecolleagues of hers from the Oxford Public School at Charkop, where Meeta worksas a student counsellor and they leave.

“Bestrong,” says one, in an orange saree.

It is a small drawing room, with a sofa at oneside and a bookcase on the other, on which are placed a television set and amusic system, while a guitar, encased in a cloth cover, is propped up againstone corner.

Onthe walls, there are three oil paintings of Lord Krishna, done in a deep hue ofblue. She would tell me later that painting is a hobby. Besides Meeta, there isher brother, Hasit, her father and mother, two brother in laws with family,childhood friend Mayur Desai, and daughter, Esha, 16, wearing square blackspectacles, and a white T-shirt with ‘Germany’ written across it.

I ask Meeta about how she heard the news and shesays, “I was at a friend’s place when he mentioned the television wasannouncing bomb blasts on the local trains. I rushed home because that was theexact time when Tushit was usually on a train.”

On July 11, 2006, seven bomb blasts on the suburban rail network in Mumbairesulted in 189 deaths and over 700 injured. It was orchestrated by the terror outfitLashkar-e-Taiba and Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence

Meetatried several times to call his mobile, but could not get through. “I told mydaughter Esha, ‘Keep on trying, keep on trying,’ she says. “All the lines werejammed. No calls were going through.”

In the end, it was a girl who was travelling inthe compartment next to the first class compartment, which blew up atJogeshwari, who got through to an uncle who called up Hasit. She had found thewallet and mobile phone.

“Iassume it must have fallen from his pocket,” says Meeta. “She told the uncle,Tushit was being sent to one of the hospitals but she could not say which onebecause she was not allowed to get into the ambulance.”

So Meeta and Esha, along with a neighbour andhis wife, rushed to Goregaon, where they checked the municipal hospital there.But the hospital authorities directed them to go to Cooper Hospital in VileParle. From South Mumbai, Hasit and his parents, an uncle and a cousin had alsoset out for Coopers while Mayur set out from Dahisar.

When they reached Cooper’s, it was a completechaos. “It seemed like a slaughter house,” says Meeta. “The bodies were allpiled up, one on top of the other. We had to trample over different bodies tocheck.”

Says Hasit: “The hospital manpower and themanagement were grossly inadequate. The hygienic conditions were the worst thatone could see. These government hospitals are a disaster.”

Finally, the authorities stationed the bodies ina streamlined manner and Tushit’s body was discovered by Mayur. After that,there was the hassle of getting the permission to take it away.

“Initially,there was talk that all bodies would be released only after a post mortem,”says Hasit. “Naturally, this did not go down well with the people. Then a neworder came which stated that the post mortem would be done on those bodieswhich had not been identified.”

There were more hassles: The police and therailway police had panchnamas to be filled. Therewere three copies to each but since there was a shortage of carbon paper and nophotocopying machine, each copy had to be filled in individually or photocopiedlater.

“Therewas a long queue,” says Meeta. But, thankfully, several Juhu VikasPradarshan Yojana volunteers were around to provide coffee, water, bananas andbiscuits; people in the neighbourhood rushed to get forms photocopied. In theend, the Shahs were able to take Tushit’s body out at 3.30 am.

Meeta is shaking with sobs now. Mother anddaughter cling to each other. Esha does not cry: tears just flow down her facesilently. It is too painful to see. I look outside. There are plants placed onpots just outside the window on an iron grille. I can hear the chirping ofsparrows. At a distance, there is a wide expanse of mangroves. When sherecovers, I ask her of the last time she saw her husband alive.

“I saw him last when he left for his Worlioffice at 7.15 a.m.,” says Meeta. (Tushit worked as an equity dealer with BricsSecurities Limited). “We had tea, he had toast and butter and he was veryhappy.”

Esha,who had finished her Class Ten exams, had just got her admission confirmed innearby Patkar College with great difficulty. “I had to formally get Esha’sadmission that day,” continues Meeta. “So he told me, ‘Go fast and geteverything done, we will go out for a celebratory dinner.’”

Tushit was wearing black trousers and a whiteshirt with thin, red lines. “It gives a tinge of pink from a distance,” saysMeeta. “I had selected it and it was one of my favourite shirts. My husbandloved light colours.”

When I ask her whether he had any hobby, shesays, “He always wanted to learn to play the guitar, because when he wasyounger, he could not afford to buy one.” Wife and daughter presented him witha guitar on his birthday, three years ago.

How was your marriage, I ask.

“Tushitmeans heaven in Sanskrit, what else can I say,” she says. “I had a mostbeautiful marriage. On December 11, we would have completed 20 years. He saidthat on our 25th wedding anniversary, our daughter would be celebrating her21st birthday and we should have a big party.” Meeta bursts into tears butrecovers quickly and says, “Tushit had a lot of dreams for us.”

He had wanted to take a loan and buy a largerflat, so that Esha would have a room of her own. He also wanted to buy someproperty in his hometown of Baroda. And he had dreams for Esha. His daughterhad secured 88 percent and a family friend, Vivek Mahajan, a professor ofphysics at National College had suggested that Esha should try to get admissionfor IIT.

“Aimfor the sky,” the professor had said, and Tushit had seconded it.

Asked about her husband’s qualities, she says,“He was very quiet, loving, affectionate and caring. He would never get scared,no matter how hard the challenge. He would say, ‘Difficult days will come butwe should never run away.’ He went out of his way to help people. My husbandtaught me to be strong. Now I will see how much he has taught me.”

The silence hangs heavy in the room as I say mygoodbye. Downstairs, when I step out of the elevator, I see that the Shah’spost box has a few letters in it but it has not been collected.

Atthe housing society office, I meet retired administrator G.M. Mehta, who usedto work in Mafatlal. He tells me Tushit was the secretary of the society. “Hewas a gentleman, who co-operated with everybody,” he says.

Atthe gate, Brij Mohan, the guard who works for the Shivam Security Services,says simply, “He was a very nice man.”

Ispot Mayur, who is rushing back to his TV repairing shop, and I ask him todescribe the body when he saw it first.

Itis too heart-rending to put it in words.

Upcoming post: Meeta talks about life since that fateful daythat changed her life.