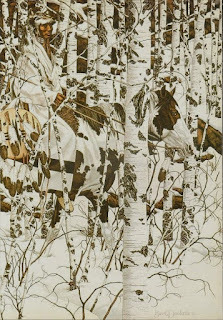

Trees and Indians.

Years ago,I lived on Oak Street. Living there always brought to mind the old joke thatwhen real estate developers start a project, they cut down all the trees and thenname the streets after them.

Something similar, only infinitely more tragic, has taken place since the firstEuropeans set foot on land that was to become the United States of America: ourforefathers—government, military, business interests, and ordinary citizens—allbut exterminated the Indian tribes that already lived here, then named things afterthem. States, counties, cities, towns, rivers, lakes, mountains, canyons,valleys, and more carry names derived from Native American languages.

Of our United States, 27 of them—27!—carry names that come from the languagesof the tribes that occupied the land before being forced off by one nefariousmeans or another.

Here in my home state of Utah (named for the Ute Indians) there are fivecounties with Indian names, along with three cities and towns, at least onemountain and two mountain ranges, and a whole lot of other stuff. And Utah isnot unusual—in fact, there are many, many states whose maps are marked withmany, many more names borrowed from Indian words.

I suppose in some sense it is a sign of respect. But it is impossible tobelieve that whatever smidgen of honor is involved in any way scratches thesurface of the damage we have done—and still do—to the people who lived herewhen our ancestors arrived.

(ABOVE:The Indian riding through the trees is a work of art by Bev Dolittle)