Google Sheets has a new AI function — how does it perform on classification tasks?

A new AI function is being added to Google Sheets that could make most other functions redundant. But is it any good? And what can it be used for? Here’s what I’ve learned in the first week…

The AI function avoids the Clippy-like annoyances of Gemini in SheetsAI has been built into Google Sheets for some time now in the Clippy-like form of Gemini in Sheets. But Google Sheets’s AI function is different.

Available to a limited number of users for now, it allows you to incorporate AI prompts directly into a formula rather than having to rely on Gemini to suggest a formula using existing functions.

At the most basic level that means the AI function can be used instead of functions like SUM, AVERAGE or COUNT by simply including a prompt like “Add the numbers in these cells” (or “calculate an average for” or “count”). But more interesting applications come in areas such as classification, translation, analysis and extraction, especially where a task requires a little more ‘intelligence’ than a more literally-minded function can offer.

I put the AI function through its paces with a series of classification challenges to see how it performed. Here’s what happened — and some ways in which the risks of generative AI need to be identified and addressed.

Classifying data with Google Sheets’s AI functionHere are four journalistic scenarios where an AI function might come in useful — along with a potential formula:

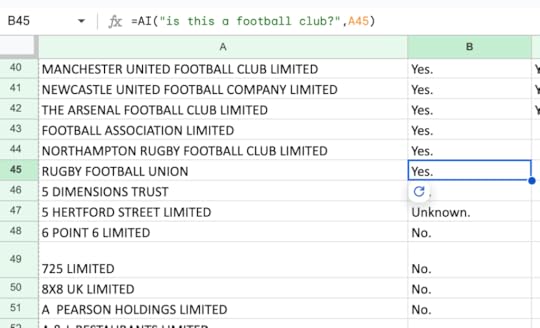

Classifying company names to create a filtered data set to investigate: =AI("is this a football club?",A2)Classifying names for a story on the gender balance of people named in the data: =AI("What gender is this name? Include a percentage confidence level in the response.",I2)Classifying addresses in order to compare north versus south: =AI("Is this in the north or south of the UK? Explain your answer",A2)False positives outnumber false negativesThe AI function performed well with the first task of classifying company names. Even names not obviously linked with football (CPFC Limited and NSWE Sports Limited) were correctly classified.

But it did less well with names that contained terms related to the sport, like ‘rugby football’ (not the same sport), the Football Association (a governing body) and even ‘One Manchester Limited’ (hypothesis: “Manchester” is heavily linked with football in the model’s training data).

When asked to classify football clubs AI generates more false positives than false negatives

When asked to classify football clubs AI generates more false positives than false negativesIn other words, the AI function erred on the side of false positives (an incorrect “Yes”) over false negatives (an incorrect “No”, as might have been expected with NSWE Sports Limited). In fact, there were no false negatives in the two test samples.

For practical purposes, this means the AI function could still be used to save time by producing a shortlist of ‘positive’ classification before manual checking to remove false positives.

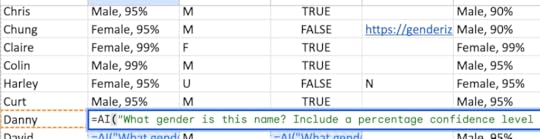

Gender classification: looking for biasesAttempting to classify gender using the AI function was revealing. You might think a name like “Lisa” would be simple for an AI model to classify — but that wasn’t the case when a job title appeared alongside it.

When asked to classify “Lisa Leighton (Managing Partner)”, the formula decided to go for “male”. In fact, it overwhelmingly classified female names as male where a senior job title was listed alongside it — with some notable exceptions. “Helen Kilvington (Chief People Officer)“, for example, was classified as female.

Splitting the information into different cells didn’t appear to improve the results, suggesting that the AI function is influenced by data in other cells in the same row, even if the formula doesn’t include them. For example, when manual M/F classifications were added in a new column, the formula suddenly started to become very accurate.

To isolate the formula from the potential influence of other columns, I moved it to a new sheet containing only first names. Without the job titles in the same cell, or the same row, it became much more accurate, getting 99% of the names right.

The AI function correctly classified most forenames, but was overconfident and inconsistent with ‘Chung’ and biased with ‘Harley’

The AI function correctly classified most forenames, but was overconfident and inconsistent with ‘Chung’ and biased with ‘Harley’ It remained overconfident, however. The name Chung, for example, was classified as male with a 90% confidence, but male. And no classifications were given a confidence ranking below 90%, despite some of the names being very rare. Re-running the formula generated a 95% confident classification as female.

Significantly, the only name the AI function got wrong was Harley, which it ranked as 95% likely to be female. Genderize.io puts it at . Could the misplaced confidence be purely down to the dominance of one woman — Harley Quinn — in training data?

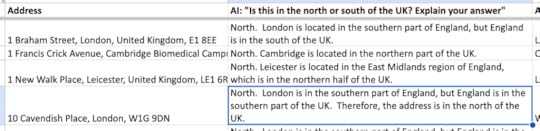

Classifying locationHumans struggle to agree on whether certain places are in the north or south of the UK, so I was interested to see how a trained algorithm dealt with such a subjective question as =AI("Is this in the north or south of the UK? Explain your answer",A2)

The answer? Badly.

Not only did it get easy locations wrong, its logic was flawed and applied inconsistently.

London, for example, was classified as both south and north, in roughly equal measures. Its logic for classifying it in the south was explained as:

“London is located in the southern part of England, but England is in the south of the UK.”

OK…

Google Sheets’s AI function gave some unusual logic for classifying London in the south of the UK

Google Sheets’s AI function gave some unusual logic for classifying London in the south of the UKInconsistency continued to be a problem when a less subjective question was asked: =AI("What local authority does this address come under? Explain your answer",A2)

In theory the algorithm should have been able to identify a relationship between the postcode and the local authority — and in some cases it did this. One of the best results was: “the local authority is likely Westminster City Council, as NW1 is a postcode district within the Westminster area of London. However, this is an assumption based on the postcode; definitive confirmation requires a more precise address lookup tool.”

Not only did it classify correctly, using the right method, but it also identified uncertainty in the answer and recommended further verification.

This wasn’t typical, however. Many of the answers weren’t actually local authorities at all: instead it hallucinated names that were plausible, but not quite right. On other occasions it said “More information is needed to identify the specific local authority.”

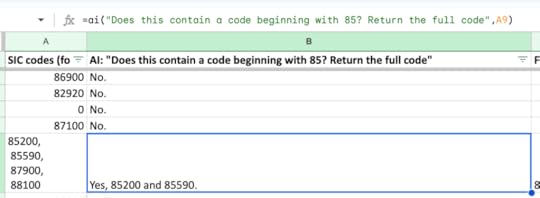

Classifying a series of codesThe three scenarios so far had been intentionally difficult — so I tested an extra, easier, scenario which involved classifying a column containing lists of industry codes (such as "56102, 85200, 85590, 88100").

Knowing that codes beginning with 85 indicated companies operating in a particular sector (education), I wrote this formula:

=AI("Does this contain a code beginning with 85? Return the full code",A2)

On this task, the AI function achieved 100% accuracy with a random sample of 100 entries, successfully identifying and extracting matching codes regardless of their position in the cell. It forgot to include “Yes” in its response once, but that was it.

Pushing it a little bit further by testing entries where ’85’ appeared in various positions and combinations, it did make one error, classifying "1, 59085” as a match despite it ending with 85, but this was the only time it did so. Other codes ending with 85 were correctly classified as non-matches.

Identifying the risks of using an AI formula

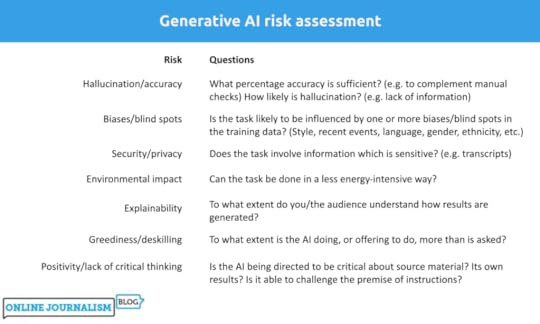

Before using the AI function, it was important to assess the risks involved. The most common risks in AI include:

Accuracy/hallucinations: does the task require 100% accuracy, or will 90-95% be sufficient? (e.g. to complement manual categorisation)Biases: is the task likely to be influenced by one or more biases in the training data? For example, classifications of gender or language will be shaped by how gender and language is represented in the model’s trainingSecurity: does the task involve data which is sensitive?Environmental impact: can the task be done in a less energy-intensive way?Explainability: do we know how it arrived at the results?Accuracy is the most obvious and pressing risk for a journalistic project — and some systematic testing can be very useful in establishing how accurate any formula is likely to be.

With the company classification task above I created two ‘test sets’ to check the accuracy of the formula:

A test set of completely random companies; A test set of companies selected intentionally for their potential to generate false positives and negatives.The first set helps to establish a broad idea of accuracy, but the second set helps to identify how the algorithm performs on ‘edge cases‘: examples that you might expect it to falsely classify one way or another. This is also where biases are often most obvious.

In the company codes, for example, the ‘edge cases’ included fictional codes ending in 85, the code ’85’ on its own, ’85’ appearing in the middle of codes, and codes beginning with 85 but appearing in the middle or end of a list. (With the other two scenarios, the function performed so badly on initial tests that there was no point testing on edge cases.)

Performance against those tests can help you decide whether the algorithm is suitable for your purposes (the level of accuracy you need), and what other steps are likely to be needed (e.g. checking for false positives, or checking for false negatives).

Improve explainability through prompt designOne of the ways to address explainability is to include a request for explanation in the prompt. Adding “explain your answer” to the geographical classification formula, for example, provides a little more context around the results (although there is some evidence that models’ explanations don’t necessarily reflect the real reasons for their results).

With the gender classification scenario, for example, when "explain your thinking" was added to the prompt, responses made it explicit that job titles were being factored into the decision:

"The name "Alisa" is predominantly used for females. The title "Finance Director" is not gender specific."

7 prompt design techniques for generative AI every journalist should know

Prompt design techniques are just as important when using the AI function as in any generative AI tool. Providing context, for example, can improve results. Here’s an example of a more developed prompt for the code classification task, which includes context and prompt design strategies such as role prompting and negative prompting:

"You are an expert on UK SIC codes, which classify a company by the sector or sectors that it operates in. Classify this cell indicating which sector or sectors they represent. If you do not know, say that you do not know. Explain your thinking, including any sources you used"

The UK aspect, by the way, also addresses the likely US bias in the model’s training.

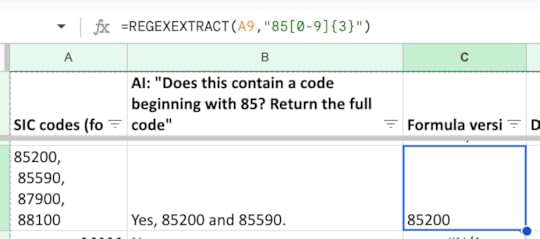

Environmental impact: do you really need AI? The REGEXEXTRACT function can be used to achieve similar results to the AI function in this scenario

The REGEXEXTRACT function can be used to achieve similar results to the AI function in this scenarioMany of the scenarios explored here can be addressed without the need for AI. Extracting SIC codes can be done with a REGEXEXTRACT function, and the same function could be used to identify 90% of companies likely to fall within a category such as ‘football team’, reducing the manual part of classification to a manageable projcet.

There are APIs for classifying addresses as falling within various administrative areas, or for classifying names and providing a confidence measure for the classification — and with better performance. Admittedly, this ramps up the technical knowledge needed — but if you have that knowledge, or access to it, then it’s a less energy-intensive option to take that approach instead (and also addresses explainability).

If a project does use AI, planning can help reduce unnecessary energy usage: drafting prompts in advance carefully — rather than defaulting to trial-and-error — can avoid unnecessary repeated prompting. And when prompts are tested, using small samples first before applying them to the whole sample can also reduce environmental impact.

Even then, AI is likely to be the tool of last resort in most projects, given the combination of environmental impact and other risks — and it can also be more time-consuming.

Prompt engineering, design and running is time-consumingWhile generative AI appears to offer a faster way to arrive at a certain result, don’t underestimate the time needed to design and refine the prompts to get effective results. You may need to run formulae multiple times.

Factor in the fact that AI formulae are slower than normal functions to return results: a few seconds per cell. In the scenarios above the full dataset had 11,000 rows, which would have taken at least four hours to classify.

Finally, AI formula results have a tendency to disappear when changes are made to the spreadsheet (such as sorting, applying a filter, or even renaming the sheet). To avoid this adding extra time to your project, copy and paste the results as values only as soon as the formulae have run.

If you do find a useful application of the AI function, let me know — I’d love to see examples of it used in stories.