Gladiator spiders

In June 2006 I was in Ghana with a group of conservation biologists to gather data and arguments for the creation of a new national park around the spectacular and highly threatened Atewa Forest Reserve, a lofty goal that, alas, has still not been reached. Sweeping my insect net through the lush vegetation, I knocked down from an epiphyte-covered branch a strange, green spider. It had a fat, flattened body that resembled a piece of moss. Looking closer, I noticed its huge, forward-facing eyes and realized that it must be a net-casting spider, a member of the family Deinopidae, but one that did not resemble any of the species that I was used to seeing in the rainforests of Central and South America. Later that day I found another individual of the same species, this one holding its gladiator net, which confirmed my initial suspicion. It turned out to be Asianopis guineensis, a species known only from its holotype described in 1940.

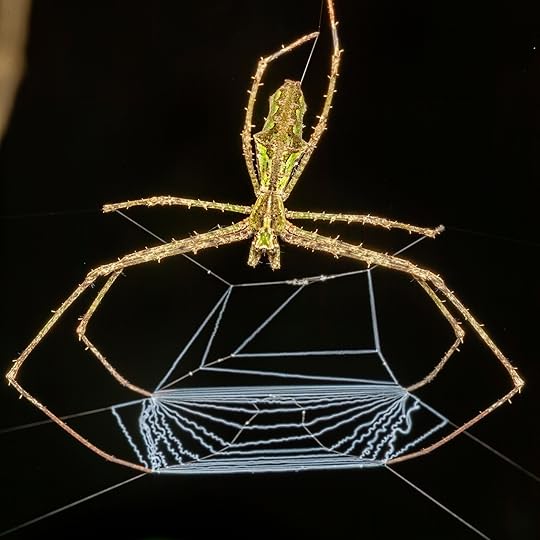

I had since forgotten about this brief encounter but recently I ran across an interesting paper describing the behavior used by the net-casting spiders to catch flying insects, which made me think of it again. Net-casting spider, known also as gladiator or ogre-faced spiders, stand out among their silk-spinning kin thanks to an unusual way of catching prey. While most net-making spiders employ a passive, sit-and-wait hunting strategy, deinopids use a small “hand-held” net to actively capture their victims by casting it over them with a remarkable speed. The net is made of tightly packed, non-sticky silk that can be stretched many times over without breaking. Its densely coiled, thin strands work like a very fine, flexible mist-net that bird and bat biologists use to capture their animals. Each tiny loop catches on the spines and protuberances on the victim’s body, enveloping and immobilizing it, allowing the spider to deliver its kiss of death and further wrap it in a layer of silk.

To detect their prey deinoipids use two separate senses. Their huge eyes provide them with an unparalleled ability to see at night. The light-gathering ability of deinopid eyes is an astounding f/0.58. If you ever used a camera then you know that the “f” number, or the aperture of a lens typically starts at around f/3 and goes up to over f/20 – the lower the number, the greater the ability to gather light. Man-made lenses have high f numbers, which is why we need flashes, tripods, reflectors, and other implements to help the camera gather enough light to create a well-exposed picture. The human eye, with the iris that adjusts its diameter to adapt to different levels of light, spans the range of f/2.1 to f/8.3. The difference between the spider’s f/0.58 and a human’s f/2.1 seems deceptively small but it means that the deinopids’ sensitivity to light is 2,000 times greater than that of the human eye, and hundreds of times greater than that of a cat (f/0.9) or an owl (f/1.1).

To achieve such an incredible sensitivity, which allows them to spot small insects in pitch black darkness, deinopids have evolved a unique eye structure that disintegrates every day, only to rebuild itself at night. Each of the spider’s big front eyes (technically, posterior-median eyes that moved to the frontal position) has six special light-sensitive structures called rhabdoms, connected with a membrane. The volume of that membrane dictates how much light an eye can gather. At night the membrane is rapidly synthesized, dramatically increasing the light sensitivity of the eye but when the day comes the membrane dissolves, leaving only enough for basic vision. But why? Wouldn’t it be great to have super vision 24/7?

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain this phenomenon and the most plausible one is that such an ultra-sensitive membrane ages very quickly, leading to a progressive loss of its sensitivity. It thus makes more sense to reabsorb it when it is not needed and synthesize it anew when it is.

The insects that deinopids catch are quite large compared to the spider’s body and one would think that a single cricket of nearly equal weight would be enough to satisfy it for the night. But no, as soon as the prey is captured the spider begins to eat it, while at the same time setting up its net for another strike. It is possible that the spider’s voracious appetite is driven by the energy-hungry physiology of its eyes, which might have caused some net-casting spiders (the genus Menneus) to forgo the fabulous night vision and reduce their eye size in a process known as regressive evolution.

Remarkably, net-casting spiders can catch insects without ever seeing them or, since spiders have no ears, hearing them. If a flying insect makes a mistake of coming too close behind the spider’s back, it will be met with a blindingly swift backwards strike of the net, deployed with the speed of 60 ms. (To use another photographic reference, the shutter-lag of an average camera, which is the time that elapses between you pressing the shutter button and the camera taking a picture, is between 50 to 200 ms. In other words, these spiders are freaking fast.) Experiments have shown that even blinded deinopids can detected flying prey from two meters away, solely by the sound of the beating wings and precisely direct the strike, all without having ears. It is still unclear how these animals detect sound, but it is likely that the structures responsible for it are trichobothria (“hair”) on the legs of the spider that respond to the movement of air molecules caused by sound waves. The tarsus, or the foot of the spider appears to be particularly sensitive to sound.

All of this is very cool but the thing that really impressed me about net-casting spiders is the incredible effort that females put into building the most beautiful protective shield around their eggs. Last year I was standing in front of my house in Costa Rica, listening to the night chorus of insects and frogs when I noticed a female building an egg sac. It was a perfect orb, suspended on a single strand of silk, and the female seemed to be continuously measuring its smoothness and size with her pedipalps, every few seconds applying a few microscopically thin strands of silk to make it even more perfect. I watched her for a while and took a few pictures, hoping to see over the next few days how she would combine her maternal duties with her hunting activity. Alas, the next morning both the spider and her beautiful maternal work of art were gone, and I will never know if she carried it to a safer location or if a bird swallowed both miracles of evolution. ✦

P. S. If you would like to read more about these spiders and see some really excellent photos and videos, visit Gil Wizen’s blog.

Piotr Naskrecki's Blog

- Piotr Naskrecki's profile

- 9 followers