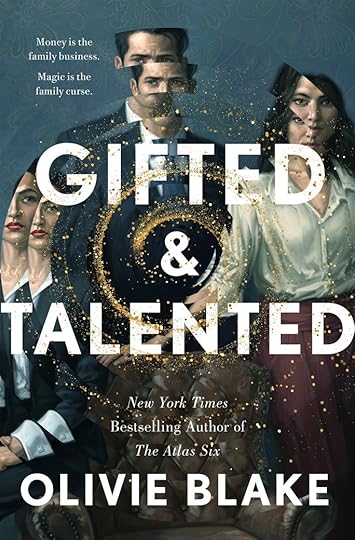

You Love to Hate Them: An Interview with Olivie Blake

In Gifted & Talented, Olivie Blake showcases her ability to make you love a character you would hate in real life. The Wren siblings are an obnoxious trio of trust-fund billionaires with a multitude of daddy issues & gifted child burnout syndrome, and yet by the end of the book you can’t help but cry for their failures as if they are your own. I was so excited for the opportunity to dive in and ask Olivie all my burning questions!

—Rachel Randolph, Parnassus bookseller

Rachel Randolph: Gifted & Talented focuses on a large cast of characters, all wrestling with love and ambition in their own distinct ways. When drafting, how do you get to know these characters and their voices? Do they ever do things you wish they wouldn’t or you did not plan for?

Olivie Blake: Oh, I never know what these silly little guys are going to get up to and wouldn’t begin to know how to tell them what to do. G&T was an especially lawless process because it was the first manuscript I worked on after concluding the Atlas series. While I was working on Atlas, I was pretty effectively using a “living outline” for each book where I’d skeletally divide the story into 8 or so parts and then flesh out each section as I arrived there, with four POVs for each part balanced between the six characters. But each time I tried to follow the Atlas process for G&T—i.e., stopping myself every 20k or so to be like “hey Olivie, where is this going?”—I’d just shrug and keep writing because I didn’t yet know the answer. Which is my long-winded way of saying I’m a pantser at heart, and this book was proof that I don’t actually know how to write a book; one magically manifests by sheer force of will, and that’s the artistic process, baby. One thing that’s always true, though, is that I don’t start writing until I understand 1) the form the novel will take (what the structure will be, which perspectives will be included, who is narrating and how) and 2) what the narration sounds like. Even more so than my other books, this story is really not driven by plot—what’s important are the emotional stakes and voice, and those things usually take shape naturally as I explore the character dynamics.

RR: The narrative voice is a distinct character all of their own. Without getting into spoiler territory, did you always know this voice was the way the story needed to be told?

OB: Yes! This is what I mean by choosing the form in advance. 99% of the time I will choose a particular mechanism for no other reason than because it amuses me. In this case, I thought it would be funny to use a supposedly objective narration style only for the narrator to gradually reveal themselves to be not only not an objective lens on the story, but also wildly biased against the story’s main characters. As an author, I think about the reader a lot—not so much what the reader wants or expects, but what emotions I want them to be experiencing as they read. So I thought about the reader experiencing the story like “hey wait, I think this voice of God narrator is expressing opinions, what gives?” and went from there. Sometimes this narrator is even making things up for their own amusement. It all just seemed like a fun, interesting way to tell what is otherwise a straightforward story we’ve all heard versions of before.

RR: I must confess, there were a few times I nearly threw the book out of pure surprise. The dramatic timing is spot on in each of the many plot lines of Gifted & Talented. Is that timing intuitive or is it trial and error? How do you decide when to hold your cards close and when to reveal?

OB: Ha, so, as I was writing, I did ask myself: does it matter if someone sees this twist coming? And because each time I was like no, it’s fine, how we arrive there is much more important than the existence of the twist, I kind of forgot that some people wouldn’t predict those moments—until my husband literally gasped aloud while reading (which has never happened before). I promise that with some books I’m more methodical than others, but this one was very much an intuitive process. I was treating it a lot like a soap opera—my grandma loved American soaps, my mom loved this one Filipino show, Maalaala Mo Kaya, which I occasionally watched parts of without understanding the language—and there were always moments like, this is so unserious. I’m gonna do it. There’s nothing more absurd than family dynamics, so it felt like the right context to explore the secrets people keep.

RR: Similar to the rest of your body of work, the novel plays with time and chronology, jumping back and forth and looping all around, yet as a reader I always felt in the right place at the right time. How do you balance the past and present narratives?

OB: There are quite a few jumps you could be referring to, but what leaps to mind for me to mention is that Meredith and Jamie’s storyline was originally a concept I’d been exploring for a contemporary Persuasion adaptation set in the tech world. One thing I’ve always said about Persuasion is that it’s super juicy (the YEARNING) but could also be astronomically juicier, for those of us who love mess, if we could see glimpses of both perspectives throughout. In terms of navigating chronology more generally, I’m a curious person and I write accordingly—I always want to know how things got here, and I want to see it for myself, voyeuristically. I’m the author who’s always going to reward your impulse to look in people’s windows. At the same time, I’m an easily bored craftsman, so I prefer to jump around and show you what I think is relevant to the present moment rather than progress through time linearly. For me, the balance is giving just enough of the past to justify the emotional stakes in the present, because the present (and more specifically, forward motion) is ultimately how the story takes shape. The story isn’t what happened then—it’s what created the circumstances for what’s happening now.

RR: Can you talk about genre and genre breaking? Gifted & Talented is categorized as fantasy, and yet it is also a family drama, corporate thriller, and grief narrative. With your self-published history and now trad-pub success, how is genre different in those two spaces?

OB: People often comment that my books break genre constraints in various ways, but I think I’m just kind of a magpie. I take the shiny stuff from all the books I love as a reader, which often happen to be genre hallmarks from thriller, fantasy, sci-fi, romance, and then applying certain literary sensibilities (mainly in my disregard for form conventions). In this case I was definitely going for family dramedy—to me, this book is heavily inspired by The Royal Tenenbaums, which I consider a film with profound emotional stakes despite its absurdist tone. The Wes Anderson aesthetic is exaggerated, distinctive, a little storybook—all things I was consciously doing with Gifted & Talented as well, because it struck me as a playful way to tell a story about what it means to be lonely, disillusioned, and, frankly, incompetent at love. I do think genre matters more to the audience than it does to the artist, which you’re right to observe is a consequence of my entering traditional publishing through my self-published backlist. Genre matters because it informs reader expectations, but it’s not that helpful for the writer, in my personal opinion. Of course, I’m functionally crowdsourced as a result of my self-published books going viral, so I’ve never really had to follow industry rules, and I’ve just… kept doing what I was doing. I think if anything I’m proving retroactively that there has always been an appetite for works that cross genre, it’s just harder for publishing to sell something there isn’t data for. But since I entered the market, I’m seeing a lot more freedom in terms of how a book can make use of “mismatched” settings, tropes, and archetypes.

RR: How long have you been working on Gifted & Talented? Does it have a different subtext than you expected coming out in 2025? How is the novel in conversation with the current state of capitalism?

OB: I actually wrote this book from June-August 2023, so before the election and before we were exposed to the extent of technofascism as we’re witnessing it now. I don’t think I really understood how angry I was about the lack of innovation in tech, or the impact that existing in a minimally effective, profit-driven, unregulated virtual landscape has had on our lives, until I’d finished writing this book. I didn’t really see it as an incisive take on the tech industry while I was writing, but everything I wrote about fraud is not about how it’s incidental to one character, but how it’s systemically enabled, because the current climate of the tech industry has pushed the fluidity and scale of capital without any meaningful contributions to match. Startup culture under capitalism, enshittification, the fact that a bunch of tech billionaires betrayed everyone politically just to hoard their personal wealth—these things are all related. And there is also a relationship to the girlboss, win-at-all costs mindset that underwrites the attitude for which the book is named. This book asks about happiness, and what happiness is or what it means or how much is possible to achieve, as something that is impossible within the sociopolitical constraints of our current system. The only true freedom of choice we currently have amounts to personal ethics, which has massively limited efficacy considering the way whole industries evade accountability. This was true when I was writing, obviously, but the transparency of corruption is currently so blatant I almost worry I’m preaching to the choir.

RR: As a chronic overachiever myself, the Wren family’s individual hungers for success felt eerily familiar to me. Why do you think so many people relate to these ideas? What do you hope they take away from Gifted & Talented?

OB: It took me a long time to stop seeing life as a series of accolades to check off. I think it’s that “gifted kid” mindset, the feeling that you have to stay ahead or you’re failing. If you’re not overachieving then you’re not achieving at all, and if you’re not achieving, you’re not deserving. It’s a particularly Millennial attitude, but probably registers beyond, where we were told we would have good lives if we just performed the dance correctly: get good grades, go to a good college, get a good job, do good work. But the reality is that completing the circuit still guarantees nothing; not to linger too long on this note, but the social safety nets aren’t there and our system is working as intended—which is to say, a few people have most of the wealth. The GATE program itself is built on system inequalities that are reinforced at every level. So what do you do, then, if you’re forced to play an unwinnable game? Structural policy changes aside, you make the best choice you can. You reframe what it means to live well. Everyone loves an ingenue, it’s customary to laud the empty space of potential, but the reality of being an adult means recognizing that your gifts and talents are immeasurable and intrinsic, and maybe there are no gold stars for making the ethical choice. But there’s no glory in compromise, and happiness doesn’t come from profitability. So maybe the success we were promised was always

an exploitative lie.

RR: And finally some bookish questions to finish us off! What novels would you consider part of the fabric of who you are as a writer?

OB: I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith, The Song of the Lioness quartet by Tamora Pierce, everything by Liane Moriarty, Vicious and the Shades of Magic trilogy by V.E. Schwab, the Neapolitan Novels by Elena Ferrante, White Teeth by Zadie Smith. This particular book was also influenced by the structure of Fleishman Is in Trouble by Taffy Brodesser-Akner, and tonally by The Idiot by Elif Batuman.

RR: What is your favorite memory inside of an indie bookstore?

OB: I didn’t marry a reader—he became one over the course of our relationship. One time he set me free at our local indie and gave me a limit of—get this!—five books. I was the kid whose parents complained about reading; I had a flashlight I used to read at night and always got in trouble. Plus we couldn’t afford more than one new book in a blue moon. So a limit of FIVE BOOKS felt tantamount to getting away with murder. And I always love an indie because it feels more like a treasure hunt, even though there are sages in the form of booksellers to help you cheat.

Gifted & Talented is on our shelves now!Ann Patchett's Blog

- Ann Patchett's profile

- 27406 followers