Shelf-Life #8: I. Asimov

This post is part of my weekly series, Shelf-Life. Each episode is about a particular book on my bookshelves. For more information see my introductory post. To read other episodes in this series, see the Shelf-Life Index page.

April 6 marks a special anniversary for me. On April 6, 1996, I began to keep the diary which I still maintain today. Four years earlier, on April 6, 1992, Isaac Asimov died. The two events are most definitely related, as we shall see.

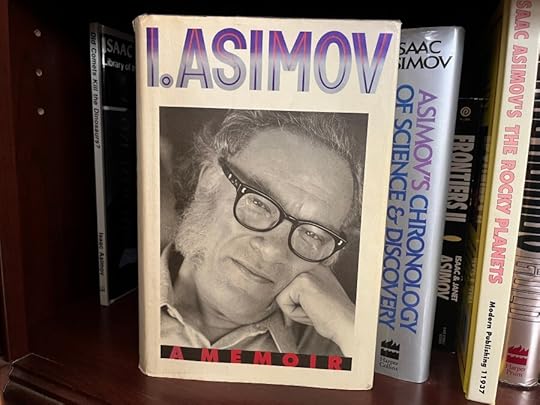

Sometime in the early spring of 1994, while wandering through a bookstore in Moreno Valley, California, I saw prominently displayed a book with a white cover and Isaac Asimov’s face on it. The title read: I. Asimov: A Memoir. Something about the book attracted my attention. Up to that point, I’d heard of Isaac Asimov, and when I was around ten or eleven years old, I’d attempted to read his novel, The Caves of Steel. I knew vaguely that he was a scientist as well as a science fiction writer. That was the extent of my knowledge. And yet, despite the $25 cover price, I bought the book. I took it back to my apartment at the campus of the University of California, Riverside, and I began to read it. In the 31 years since that day, no other book, not one, has had as much of an impact on my life as that one.

It turned out that Isaac Asimov had already published a massive autobiography, a two-volume, 600,000-word work published in 1979 and 1980 called In Memory Yet Green and In Joy Still Felt. This new volume was different. As Asimov wrote in the introduction:

What I intend to do is describe my whole life as a way of presenting my thoughts and make it an independent autobiography standing on its own feet. I won’t go into the kind of detail I went into in the first two volumes. What I intend to do is break the book into numerous sections, each dealing with some different phase of my life , or some different person who affected me, and follow it as far as necessary—to the very present, if need be.

I trust and hope that, in this way, you will get to know me really well, and who knows, you may even get to like me. I would like that.

Thanks to this memoir, that is exactly what happened to me. I got to know Isaac Asimov really well. Better, perhaps, than any other writer I have read. What’s more is how much I learned from him. Yesterday, I scribbled a list of what I’d learned from Asimov and it is easy for me to see, at least, that I would be a completely different person without those lessons. And all of this from someone who had, alas, been dead for nearly two years when I first sat down to read the book.

What exactly did I learn?

The most obvious outward example is my own writing style. Asimov’s style was unadorned and colloquial, and that was a huge influence on my own writing. Most writers I know are influenced, in some way or other, by the writers they read, but over time, they develop their own voice. Mine traces directly back to Asimov’s. Like a good impressionist, I can impersonate other styles. I did this most publicly in my story, “Hindsight in Neon” which appeared in an early issue of Apex Magazine. There, I was deliberately imitating Barry N. Malzberg’s style. But the style I tend to write in, my default mode, what you are reading now, is adapted from Asimov’s style.

I think it has served me well. I’ve sold stories, to say nothing of two lead editorial articles in Analog using my natural style. I’ve written over 7,000 blog posts in this style. If you’ve ever received an email from me, you’ll no doubt note that it is written in this style. It has become the way I naturally communicate.

It was from I. Asimov, and its two predecessor volumes, that I learned how to be a professional writer. I’m not talking about how to write professionally. I’m talking about to conduct oneself as a professional writer, how to work with an editor, what galleys were, what the unwritten rules of professional writing were. I would have known none of this. Indeed, until reading this book, my ideas of an editor came from Piers Anthony’s “Author’s Notes” where he considered editors idiots if they changed a word. Fortunately, I had Asimov to teach me better, and all of my interactions with editors have been great experiences, ones where I try to learn as much from each as I possibly can.

I read I. Asimov for the first time as the final quarter of my senior year in college was starting. I was taking an extra heavy load (24 credits—this required special approval from the Dean), and continued to work in the dorm cafeteria. One of those courses was a “healthful living” class required by my major. During that class, we had to get up in front of the entire class and give talk on a particular health-related subject. I never liked getting up in front of people and speaking. Isaac Asimov turned me around on that.

If I allow my original copy of I. Asimov to fall open at random, chances are good that it will fall open to a section titled “Off the Cuff” where Asimov details how he became a public speaker and how he tends to deliver his talks. He talks about discovering this latent talent. He had no idea he could speak in front of audiences (and off the cuff, at that) until he tried it. What, he wondered, would have happened had he never discovered this talent? I read this section over and over again, and when it came time for me to give my talk to the health class, I did it off the cuff.

I’d like to say that it went smoothly. Mostly, it did, but I had a punchline I’d intended to deliver, and when it came time to deliver it, my mind went blank. I had nervous few moments, but I got through it. And afterward—I never worried about addressing an audience again. Early in my career, I had to give a talk on a new browser called Netscape Navigator to a roomful of researchers. I prepared well, but I still delivered the talk off the cuff. Afterward, I received an email from one of the attendees, none other than the computer pioneer Willis Ware, who complimented me on my talk with a ”GOOD SHOW!” Much later, I was even paid for a couple of talks I gave to some business leaders. Without reading I. Asimov, I’m not sure I would have ever tried something like that.

There are other things I learned from Asimov that stemmed from this book. I’ve written in the past how nearly everything I learned about science I learned from Isaac Asimov. His memoir led me to his science essays which he published monthly in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction for over 30 years. These essays were collected into nearly two dozen volumes, and I read through them voraciously. There are fascinating facts and figures and speculations in essays, but much of what I learned was how to explain things in a way other people can understand them.

I admired Asimov’s generalist approach to learning and his humanist approach to thinking, both of which set me on similar courses.’

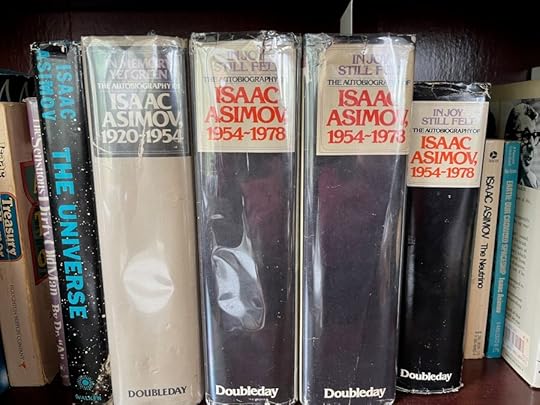

Isaac Asimov died on April 6, 1992. His wife, Janet, describes the end in the memoir. Reading it today, I still feel a pang. How I wish I could have known him in person! As I’ve said, I first read I. Asimov in the spring of 1994. I think I read it again in 1995 but I’m not certain because that was before I started keeping my list. In the meantime, I managed to obtain used copies of his previous autobiographies, and I made my way through those. In some ways, they were better because they were even more detailed.

In 1996, I had a plan. I’d start to read I. Asimov around my birthday in late March, with a goal of finishing the book on April 6, the fourth anniversary of Asimov’s passing. By the end of the book his wife, Janet, is describing his last days, which makes for a sad way to end. I didn’t want to end that way. Instead, I decided that after I read I. Asimov, I’d re-read In Memory Yet Green and In Joy Still Felt so that when I finished those books, it would only be 1980 in Asimov’s life and would be like he’s still living.

My copies of Asimov’s earlier autobiographies. One of the copies of In Joy Still Felt is a first edition. The other is signed by Asimov.

My copies of Asimov’s earlier autobiographies. One of the copies of In Joy Still Felt is a first edition. The other is signed by Asimov.That year, I did finish reading I. Asimov on April 6. I didn’t start the other books until May. In subsequent years, however, I would re-read all three books, finishing I. Asimov on or close to April 6 and then spending the rest of April reading the two earlier volumes. It was heaven and I looked forward to this “renewal” in spring each year.

Two of my fondest reading memoirs involve these books. In one, I’m sitting on the porch of my Studio City apartment, chair propped back, with I. Asimov in my lap and the warm Southern California sun on my face. In the other, I’m seated at a booth in Swenson’s on Laurel Canyon and Ventura Boulevards, sipping at a chocolate shake, and reading about Asimov’s early days in his parents’ candy store in Brooklyn in the first volume of his autobiography.

From 1996 to 2008, I never missed a year when I read all three books. If we include my 1994 and 1995 reading of I. Asimov, I’ve read that book 17 times. The last time I read it was in April 2010—except that I am finally reading it again now, and I expect to finish it today or tomorrow. What a pleasure it has been to come back to it.

The book has influenced me in two other significant ways. When I decided to re-read it in 1996, I told myself that when I finished it, I’d start a diary of my own. Asimov started a diary when he was 18 and continued the practice through his life. For him, the diary was just another reference book. That made sense to me. The opening sentence of my very first diary entry, written on Saturday, April 6, 1996 was:

I finished I. Asimov this afternoon at about 4pm, precisely as I had hoped to do.

Twenty-nine years later, and that practice continues.

Reading Asimov also saw me branch out to other writers that I might not otherwise have read, or perhaps, would have read much later than I did. Carl Sagan was one. Asimov and Sagan were friends (indeed, Sagan was one of two people that Asimov would freely admit was smarter than he was. The other: Marvin Minsky.) I started scrambling my way through Sagan’s books beginning in December 1996, and like Asimov, much to my dismay, I’d learned Sagan had died shortly before I started reading The Demon-Haunted World.

Asimov described style as mosaic or plate glass. A dense writer is like a mosaic window in a church, while plate glass is clear, and you don’t even notice it is there. Asimov introduced me to Stephen Jay Gould, whose essays I adore, but are mosaic when compared to Asimov’s plate glass style.

He introduced me to Agatha Christie and P.G. Wodehouse and Martin Gardner and Will Durant and his Story of Civilization. In countless ways he has influenced me, first and foremost through his memoir, I. Asimov. Though I never met him in person1, when I read his memoir, or his autobiography, or his science essays, or his guide to the Bible, or his Annotated Gilbert & Sullivan, he is alive for me. His voice speaks to me alone. I think I am a better person because of him.

Did you enjoy this post?

If so, consider subscribing to the blog using the form below or clicking on the button below to follow the blog. And consider telling a friend about it. Already a reader or subscriber to the blog? Thanks for reading!

︎

︎