Rewilding Comsumption

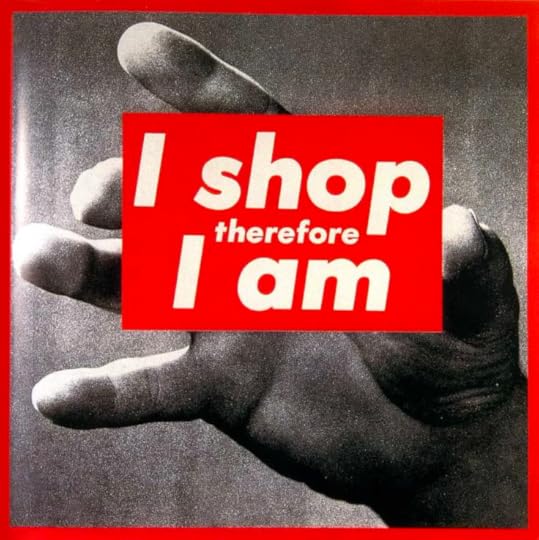

I clearly remember the first time I saw Barbara Kruger’s iconic photolithograph, I shop therefore I am (1990). As a rewriting of French philosopher René Descartes’ (1596-1650) seminal statement, I think therefore I am (Cogito ergo sum), it is a powerful and symptomatic reflection of modern consumerism.

We are first and foremost consumers. Consumption has become our primary mode of engagement, our expression of identity, our means of belonging. We hoard glittering things like magpies, collecting and displaying them as proof of status, taste, or trend awareness. Consumption has long since outgrown its roots in necessity; it has become our source of entertainment, self-expression, and even our primary form of interaction with the world. Even the most basic acts of survival—eating, drinking, sleeping—have been reshaped into lifestyle choices, marketed as extensions of personal identity. What we consume, when we consume, and even the decision to abstain from consuming something have become statements, signaling status, identity, or awareness. Even rest is now a commodity, with sleep trackers and silent retreats turning fundamental human needs into aspirational goals.

This all raises an unsettling question: if modern identity is built around consumption, who are we without it?

Refraining from purchasing fast fashion has itself over the past years become a cultivated choice—one that assumes the privilege of already having enough. It’s a quiet luxury, out of reach for those who buy clothes simply because they have to cover their bodies, not because they’re making a statement. And that’s the problem. Sustainability has become an exclusive club, reserved for the privileged few, who can afford to step away from overconsumption. But if sustainable living isn’t realistic for the majority, then what’s the point? If it’s not for the many, does it even make a difference? For a lot of us, shopping isn’t just about getting what we need—it’s a way to feel included and to have a sense of power and relevance. If we ignore that, we’re missing the bigger picture of why overconsumption happens in the first place, making it even harder to address.

Shopping sure is a potent drug. It promises hope, a feeling of abundance, novelty, and often provides a boost of confidence; and not only because of the approving gazes that might follow new belongings. The pandemic made that painfully clear. Even when our world shrank to four walls, online shopping soared—not for books, mind you; no, for fast fashion and tech gadgets, even though there was no one to show these things to! The act of acquiring became a form of interaction, a way to affirm our existence. What does this reveal about our consumption patterns? If we’re not consuming to be well-dressed for work or to impress our peers, then the acquisition of new, fashionable, tech-trendy, glittery things has become essential to our personal well-being. This reminds me of a sign I often see in a shop in Ubud that reads: “Shopping is cheaper than therapy.” I find that sign so depressing.

We need an alternative to consumerism—an anti-consumerist manifesto that can attract a following and infuse our late-modern lives with meaning and direction. And we need it urgently.

Why?

Well, because overconsumption is a ticking time bomb, an ecological disaster in motion. I’m not one for doomsday scenarios, but the overconsumption of insignificant, unsustainable, short-lived items wrapped in cheap plastic—meant to be discarded after use but never really disappearing—is one of the primary culprits of pollution. I witness this daily here in Bali. There is trash everywhere! Piles of plastic waste line the ditches, dirty brown rivers choked with plastic flow down the mountains during the rainy season, and heaps of flip-flops, toothbrushes, ice cream wrappers, shampoo bottles, and polyester shirts wash ashore, transforming the beaches into colorful patches of disaster. Discarded clothing from around the world accumulates in landfills, slowly releasing clouds of methane into the environment, and the same applies to hard plastic waste from computers, washing machines, and televisions.

Digging into the soil recently on my own little piece of land here (with the intention of making a vegetable garden), I discovered generations of plastic, preserved in layers like the remnants of a lost civilization. With virtually no waste management infrastructure in Bali, most people simply discard their trash in nature or burn it in sticky bonfires along the roads. And when a piece of land, like ours did before we leased it, sits uninhabited for a time—often occurring next to a village—it tends to become the local dump.

One might argue that this is only true in developing countries like Indonesia, and that in wealthier countries the situation is different: that waste is primarily recycled, repurposed as fuel, or transformed into a resource. But while this may hold some truth, I would like to emphasize two key points: 1. A significant portion of the waste that ends up in large landfills here in Indonesia is shipped from Europe, America, or Australia—this, as a subtle side note, represents a modern form of colonialism. While exporting waste may alleviate the consumption problem in developed countries, it exacerbates global inequality. Moreover, just because waste is out of sight doesn’t mean it’s gone. We inhabit a globe with interconnected continents and oceans, making the pollution generated by these landfills a concern for everyone! This leads to my second point: 2. Even though the worldwide waste problem may not be immediately visible in developed countries—and one may not experience the discovery of decades of plastic waste layered in the soil as I did here—there is no recycling system or process for turning waste into a resource that can keep pace with the staggering amounts of waste produced each year. Last time I checked, the figure was an astounding 2.12 billion tons of waste annually! If all that waste were loaded onto trucks, they would circle the globe 24 times.

So, while the mental image of my plastic-polluted backyard might be appalling, the layers of pollution I encounter in our garden and in our small village—plastic bottles littering the roadside, sweet wrappers scattered in the fields, diapers floating down the river—pale in comparison to the mountains of waste generated by a similarly sized European village. The primary difference lies in visibility (and, trust me, it isn’t pretty).

This is not just an environmental crisis; it is a crisis of being. To overconsume is to deplete and erode. It stands in direct opposition to sustainability, which requires slowness, repair, longevity. The churn of endless production and disposal is not just exhausting our ecosystems—it is reshaping our very understanding of value, turning disposability into a default mode of existence. If consumption defines our rhythm of life, what happens when we stop?

Upcycled kimono from Southeast Saga

Upcycled kimono from Southeast SagaRewilding might offer a (positive) answer to this question. To rewild consumption is to break free from the cultivated, modern insatiable need for more. It is to reject the idea that our worth is measured by what we acquire and instead embrace a different kind of abundance—one rooted in resilience, self-sufficiency, and deep connection. It means choosing quality over quantity, mending instead of discarding, seeking nourishment rather than novelty. It is a shift from a mindset of extraction to one of reciprocity, where what we take, we give back, and where value is measured not by accumulation but by the richness of our relationships with the world around us.

I view shopping addiction as a symptom of aesthetic starvation. When our senses are dulled by smooth and monotonous surroundings and things, we tend to overindulge in new, shiny, glittery knickknacks to fill an aesthetic void we may not even recognize. We become aesthetically malnourished, seeking empty calories to satisfy us.

As cultural anthropologist Grant McCracken observes in his recent, very recommendable book The Rise of the Artisan, a shift away from empty overconsumption is already underway—driven, in part, by an aesthetic malnutrition caused by an excess of smooth, mass-produced sameness. For decades, globalization and industrialization have pushed the world toward homogeneity, erasing cultural distinctions in favor of efficiency and standardization. Cities now look alike, their restaurants serving near-identical menus. Crafts traditions have been undermined by the flood of cheap, machine-made products.

But the hangover from this relentless uniformity is beginning to show.

As with all cultural tendencies, an excess of one thing tends to spark a longing for its opposite. The more convenience, sameness, and artificial smoothness we consume, the more we crave tactility, slowness, and variation. Increasingly, status is no longer signaled by accumulation or excess but by engagement with the handmade, the seasonal, the imperfect. The rise of the artisan reflects a deeper yearning—not for more, but for meaning.

The key to breaking the addictive cycle of overconsumption lies in changing our status symbols (easier said than done, of course, but definitely not impossible). If engaging in sourdough bread-making, growing tomatoes, reading novels, cherishing handmade products, or listening to lengthy podcasts is suddenly viewed as more status-enhancing than purchasing smartphones, scrolling on TikTok, or flaunting expensive designer clothing, the necessary radical reduction in product consumption will naturally follow.

But for this transition to take hold, it must extend beyond aesthetics into a fundamental rethinking of value. If we rewild our desires—redirecting them from passive consumption toward active creation, from disposability toward longevity—the need for endless production will naturally diminish.

A rewilded relationship with material things does not have to mean deprivation; it can actually be rather liberating! When we cease to chase the latest trends, we free ourselves from always having to keep track (yes there is a deliberating degree of JOMO, the joy of missing out, to trace here). When we let wear and tear tell a story of use rather than obsolescence, we redefine beauty. When we resist the pressure to accumulate, we make space for presence, almost quite physically actually.

Surround yourself with tactilely stimulating, visually exhilarating objects. Fill your home with (few but good, well-made) things you want to engage with repeatedly—objects to touch, wear, observe, sit on, drink from, and “share time” with. Feed your senses! Keep them alive and alert. In doing so, your need to purchase insignificant knickknacks will vanish. It’s a promise.

Perhaps this kind of shift in our view on value and abundance is the true marker of late-modern rebellion—not consuming less as a curated lifestyle choice, but stepping entirely outside the paradigm of consumer-driven identity. To rewild consumption is to reclaim our agency. And in doing so, we may rediscover a life enriched by depth, durability, and aesthetic nourishment.