Beyond Storytelling

To speak of “reading” a picture is appropriate but dangerous at the same time because it suggests a comparison with verbal language, and linguistic analogies, although fashionable, have greatly complicated our understanding of perceptual experiences everywhere.

—Rudolf Arnheim

Generalizations are dangerous things. Sweeping statements, even if true in some cases (or even if true in a majority of cases), may belie important nuances and exceptions which, if we fail to acknowledge them, may lead us to incorrect conclusions, leaving us with incomplete, flawed, or outright mistaken sense of understanding. What prompted this thought was a recent encounter with such a general statement in an article about photography. The statement was this: “photographers are visual storytellers.” Just that. No nuance, no qualification—no “some” or “most” or “aspire to be.” To my dismay, an internet search for that phrase brought up a disturbingly large number of results. I disagree.

In fact, I disagree vehemently enough that I consider this statement, indeed any generalization, potentially harmful, especially if taken at face value by those who have not yet found the form of photography most suitable and rewarding to them, and who may be discouraged by such statements from even considering forms of photography other than storytelling.

I am a photographer. (A professional one, even.) I am not and have no aspiration to be a visual storyteller. In fact, I believe that photography by itself is a very limited medium for storytelling. Rather than the bombastic and overly generalized statement “photographers are visual storytellers,” I propose that a truer and more accurate statement is this: some photographers, if they are also good wordsmiths, may—if they wish—be visual storytellers.

The purpose of storytelling is communication. Communication, to be effective, relies of parity between the information expressed by the author and the information inferred by the recipient. For such parity to exist, a certain degree of shared knowledge and meaning must exist a-priori between the person who wishes to communicate a story and the person attempting to comprehend the story.

Communication, in turn, is just one of many goals that may be achieved or aided by photographs or other artistic creations. It is, by a long shot, not the only one. In fact, the goal of much art today is in some ways the opposite of communication: it is to present viewers with ambiguous, open-ended impressions from which they may (indeed, are encouraged to) proceed to conjure their own stories, pose and attempt to answer their own questions, experience their own feelings, and make their own meaning without any of these being overtly imposed or even intended by the artist, which is to say: they are intended by design to not tell stories, to not communicate accurate, unambiguous information or precise meaning.

Photographs (or for that matter music or other nonverbal media) are certainly capable of inspiring or prompting viewers to perceive, to seek, or to conjure complex and powerful stories. However, I contend that photographs (or other nonverbal media) are very limited in their capacities for telling such stories.

It is the Achilles heel of general statements that all it takes to disprove them is just one example to the contrary. I will offer a couple, to make my point.

One example, not my own (alas, I don’t know its origin) is this: imagine a picture of a burly man striking a small girl in the street. The girl’s facial expression and tears leave no doubt that she is hurt and terrified. What is the story? A bad man hurts an innocent little girl? Perhaps. But what if you were told (verbally) that the man is a physician and the girl his patient who is deathly allergic to bee stings. Seeing a bee landing on the girl’s shirt, the physician jumped to her rescue and swatted the bee, perhaps saving her life. Certainly, the image told a story, but it could not tell the story. The image alone did not tell the whole story. Words may have but perhaps not as powerfully as the visual rendering of the scared little girl. Insisting on using just one medium or the other would have fallen short of telling the story in all its nuances. The power of the image exceeds that of words in eliciting emotions. The power of the words is in communicating precise, unambiguous details. Visual storytelling does not simply mean telling complete stories in images (which I argue is impossible, at least if a story is complex); it implies that images may be used to enhance and increase the power of a story. The conclusions: being a good storyteller is not about the medium you choose; it’s about knowing which medium is best suited to a desired effect.

Now consider the surreal paintings of Salvador Dali. What is the story told by a melting clock or a deformed face? Before attempting an answer, consider my previous statement that stories are a form of communication relying on shared knowledge and understanding of certain words or symbols. Is Dali attempting to communicate something to his viewers with whom he shares a common understanding? Not according to Dali. In his essay “Conquest of the Irrational,” he wrote: “The fact that I myself, at the moment of painting, do not understand my own pictures, does not mean that these pictures have no meaning; on the contrary, their meaning is so profound, complex, coherent, and involuntary that it escapes the most simple analysis of logical intuition.”

How about Picasso’s cubist works? Would you know that his famous 1937 painting depicting an ox, a horse, and deformed, disembodied body parts was the story of a horrific war scene if he did not title it Guernica, or if you did not know what historic event is referred to by this title? The picture does not tell a story; it prompts and challenges interested viewers to research and to construct the story from information found outside the picture.

Consider the haunting photographs of Gregory Crewdson. Ask yourself “what is the story?” then ask someone else to answer the same question, and another. What are the odds that these stories will be consistent and accurate? Accurate to what? There is no one real story. The pictures suggest stories; they challenge viewers to unleash their imaginations, to come up with their own stories, but they don’t tell stories. This is the power of photography intended as art, rather as a medium for storytelling.

My own goal in photography is not to tell stories. My goal as an artist working using the medium of photography is to create impressions hoping they may inspire stories—perhaps complex, powerful, even ineffable stories. Certainly, viewers may attempt to unravel “the” story—my story—what I felt and wished to express in my photographs. They may even be successful in this to some degree. But no matter how much a viewer may wish to believe otherwise, there is no way that anyone other than me can infer from, say, an arrangement of rocks or qualities of light in my photograph exactly how this photograph may relate to my mindset and emotional state, how these may have been influenced by the preceding hours of solitary hiking in the desert, the music or the silence I’ve been listening to. All are, to me, my story—a story I strove to express not with the hope of communicating it in all its details and nuances, but because it was meaningful to me: because I wished to intensify and to commemorate it, and because my experience was elevated by engaging in creative work—for my own sake. However, I do so also in full knowledge that the photograph will not—cannot—tell my story in all its dimensions—factual or imaginary—to anyone but me. If I felt compelled to share these aspects of my story with others, I would use words.

For nearly two decades I have been studying and teaching the expressive powers of images, investigating and striving to explain to my students the concept of a “visual language.” On my naïve early explorations, I had hoped to discover a means of translating “verbal language” into “visual language” with the goal of relating complex narratives—thoughts, feelings, and yes stories: things I could express in words, but instead using photographs. Inspired by Alfred Stieglitz’s idea of “equivalence,” I had hoped that there was sufficient overlap between verbal and visual language: a sufficiently broad range of visual cues that may be perceived as equivalent to verbal expressions in the same way that two verbal languages may be used to express the same things only using different words and expressions. This, I can say now with confidence after having studied the topic both as an artist and as a lay scientist, is not the case.

When it comes to storytelling, visual language may no doubt enhance and intensify stories, but, beyond a certain degree of complexity and desired precision, is no match for the expressive powers of verbal language. By this I mean to say that the more complex the story you wish to tell and the more precisely you wish to tell it (i.e., to ensure that audiences will infer and relate to your story in “specific and known” ways, to borrow the words of Minor White), the sooner you will exhaust the expressive capacities of visual language. On the other hand, some aspects of a story may be expressed much more effectively in visual language than in verbal language—but only some. Consider for example the difference in emotional response between describing a person being mistreated and showing an image of a person being mistreated.

Photographs may be roughly equivalent with or even superior to words in making such plain statements as, “this is what a White-Crowned Sparrow looks like,” “this person is sad,” “this view is awe inspiring,” or “I saw this happen.” But stories told in words can go considerably beyond such simple statements—to epic novels spanning many characters and prolonged time periods, explanations of complex philosophical ideas, descriptions of elaborate processes, or precise articulation of unobvious scientific theories.

Verbal language has its limitations, too. For example, in some cases where words leave off, the descriptive powers of “mathematical language” may still go further, extending to such concepts as explaining the behavior and properties of quantum particles, and how such particles that defy our intuitive perceptions of “real” may give rise to everything we perceive as real, theorizing spaces having dimensions beyond just height, width, depth, and time, even universes having laws of physics that may be different from those found in the one we inhabit: things that no amount of words can fully relate. “To those who do not know mathematics,” wrote Richard Feynman, “it is difficult to get across a real feeling as to the beauty, the deepest beauty, of nature.”

For photography to tell stories in the sense of communicating information based on a shared understanding, these stories must consist largely of elements having known and predictable connotations arousing predictable perceptions and reactions in a majority of viewers. As such, the best examples of “visual storytelling” I know of generally fall within one type of storytelling: reportage—journalistic accounts testifying to the existence of certain things or the occurrence of certain events the photographer has witnessed. As a creative artist, I find this to be a draconian and unnecessary limitation to impose on my work—draconian because my goal in photography is not to report on the visible world; unnecessary because, when I do wish to tell stories, I have at my disposal not only visual language but also verbal language, which—whether alone or with the aid of photographs—can tell such stories more effectively.

The reason photographs fall so far short of words in telling stories is that visual language is by nature and necessity ambiguous. Beyond very simplistic expression, people’s perception of what a photograph “means” or the story it may tell rely on subjective factors as much as objective, known, universal associations. Simply put, there isn’t—and cannot be—a “dictionary” for visual language. While some visual elements may be perceived without ambiguity, others may assume meanings related to cultural symbols (e.g., the color of one’s flag), one’s experiences, philosophy, or phobias (e.g., the image of a snake may arouse fear or disgust in some, fascination in others). While verbal language is not entirely free of such subjective perceptions, it is far less susceptible to them.

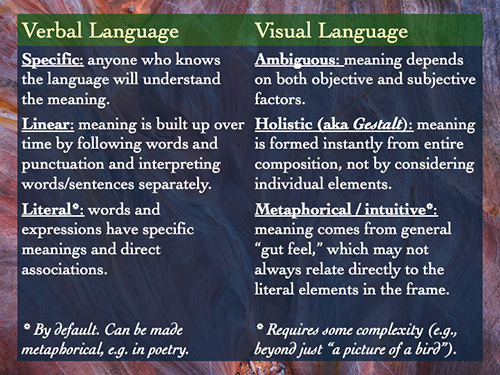

Those who attended my classes may recall this summary slide used in my discussion of visual language, explaining how it differs from verbal language:

Other than the inescapable ambiguity inherent in visual expression (which increases with the complexity of what is being expressed), the second point—regarding how our brains make meaning from visual information vs. verbal expressions—is crucial. Our visual processing depends on momentary impressions—gut reactions—formed by our brains, which take in a large amount of information from our sensory organs and must distill salient information from it as quickly as possible. Most of this information is discarded—filtered out—according to so-called “rules of Gestalt” before it ever reaches our consciousness. This is very different from the way our brains process verbal information (in specialized structures such as Wernicke’s area and related areas), which consider a much larger portion of the information conveyed in words, their order, punctuation, possible meanings in different contexts, etc.

Photographs may certainly enhance stories—make stories more relatable and visceral—but photographs cannot tell stories, at least not ones with any significant degree of depth or complexity, without prompting viewers to go beyond the photographs: to fill in information from other sources and media. Also, photographs may be created without any intent to tell stories, but to create powerful impressions, to arouse emotions, to give rise to aesthetic experiences not intended to communicate any information. To suggest that all photographers are storytellers without further qualification is like saying that all writers are reporters or authors of cookbooks. Photography can tell stories, but it’s not limited to telling stories. It is for each photographer to choose how to employ their medium for their own purposes and according to their own motivations, whatever they may be.