More than Half of the Curated Crime Collection Is Now Available

The fifth volume in the Curated Crime Collection is available for sale. Titled The Rise of Ruderick Clowd & In the Bishop’s Carriage, it combines two distinctive crime novels, the first by Josiah Flynt (1869–1907) and the second by Miriam Michelson (1870-1942).

These two works fit nicely together because of their parallels. Both were written by American authors and debuted in 1903. Both lead characters, whose crimes lean toward picking pockets and burglary, are products of poverty and “the streets.” Both characters grapple with a crisis of conscience when their criminal activity forces them to, at least, consider committing homicide.

However, the two works are also very different, especially in tone. Ruderick Clowd is a work of stark realism, a piece in the tradition of Stephen Crane’s 1893 novella Maggie: A Girl of the Streets and Frank Norris’s 1899 novel McTeague. Flynt’s title also calls to mind other realist novels dealing with complex characters struggling with complicated moral choices: William Dean Howells’ 1885 The Rise of Silas Lapham and Abraham Cahan’s 1917 The Rise of David Levinsky.

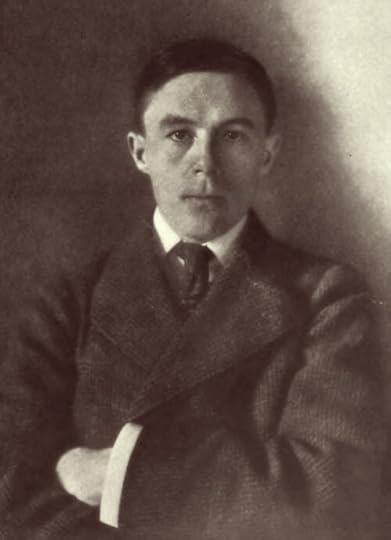

Josiah Flynt

Josiah FlyntAn example of Flynt’s gritty realism — and his critique of the prison system — appears when a prison chaplain urges the incarcerated Clowd to do better. The hardened inmate replies:

This ain't the place for anybody's conscience to get in its work. . . . You send a fellow here for ten years, shut him up in a cell, put a crowd o' fellows around him him just like him, and then tell him to be good. You might as well tell him to go and catch fish out in the courtyard. I know where I stand, and I know why I stand there, too. I'm a crook, and you know it and the whole prison knows it. I was sent here for doin' crooked work. I admit all that, and I ain't kicked at what I've had to go through. But don't you get it into your head for a moment that I'm thinking o' losin' the good times that are comin' to me when I'm turned loose.Despite Clowd’s apparent lack of conscience here, some chapters later, readers come to learn he has one:

It all might have been very different; everything had been carefully planned that it should be very different; but -- Ruderick Clowd's conscience had interfered.Indeed, a reader might have wondered if Flynt’s title should’ve been The Fall of Ruderick Clowd, given the character’s descent into street crime, mob heists, prison life, and failed love relationships. But the author provides an ending that is both believable and — maybe not happy exactly — but happy enough. One shouldn’t ask too much for someone who’s experienced all that Ruderick Clowd has.

Miriam Michelson’s Nance Olden, on the other hand, is something very different. Michelson worked as a drama critic, and her knowledge of backstage life and onstage theatrical flair come into play. In fact, In the Bishop’s Carriage has enough narrow escapes and coincidental meetings that Michelson transports the feel of farce from the stage to the page.

Miriam Michelson

Miriam MichelsonAs a result, Nance Olden becomes an entertaining and capable female — role model isn’t the right word, so let’s settle for protagonist — in an era when women’s roles were changing rapidly. Remember, this is the generation that won the vote for women.

Still, the evolution from street criminal to stage performer is not an easy one. Dazzled by a diamond worn by someone who shares the stage with her, Olden finds herself easily tempted to fall back into her illicit ways:

I shut the door.But not behind me. I shut it on the street and -- Mag, I shut forever another door, too; the old door that opens out on Crooked Street. With my hand on my heart, that was beating as through it would burst, I flew back again through the black corridor, through the wings and out to Obermuller's office. With both my hands I ripped open the neck of my dress, and, pulling the chain with that great diamond hanging to it, I broke it with a tug, and threw the whole thing down on the desk in front of him.

"For God's sake!" I yelled. "Don't make it so easy for me to steal!"

Like Ruderick Clowd — and despite the very different tones of the two novels — Nance Olden has to struggle to establish a new life for herself.

I’m proud and pleased to have reissued these two novels. I think both are important contributions to American literature of the early 1900s, and — as partners in crime — Flynt’s Clowd and Michelson’s Olden illustrate the breadth found in crime fiction of that era.

— Tim