Shelf-Life #3: John Adams

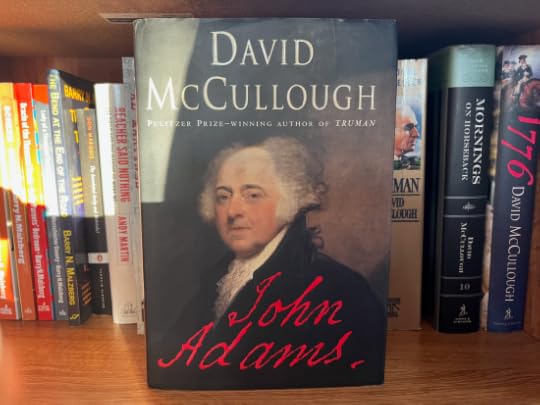

Some books are like the pebbles that start an avalanche. John Adams by David McCullough was one such pebble for me. In the late spring of 2001, one could not walk into the Book Star near the corner of Laurel Canyon and Ventura Boulevards without seeing row after row of hardcover editions of John Adams arrayed at the front of the store. I don’t know exactly what it was that attracted me to the book. I wasn’t a biography reader. But at some point, probably on June 2 or 3, I finally forked out the money for a copy. The first mention of the book in my diary was on June 5, 2001: “I am absolutely loving John Adam—possibly the best book I’ve read this year so far.”

This was a book I savored. By the next day, I wrote that I was nearly 190 pages through the book and “eating it up!” On the 13th I was through 450 pages. Back then, I didn’t read as much as I do today; I could linger over a book for a month or more. I finally finished the book on July 2, 2001, while in Castine, Maine. On that day I wrote, “Spent most of the afternoon on the deck under beautiful, partly cloudy skies and warm sun, reading and nearly finishing John Adams. It was the ultimate relaxation, and I tried to relish every minute of it.” Later that day, I finished the book “and it was definitely the best book I’ve read this year so far.” It turned out to be one of the best books I’ve ever read, period.

John Adams caused an avalanche in me. At least three things changed after I read that book, slowly, like the pebbles gathering speeds through the force of gravity. It made me love biographies. It created in me a fascination with U.S. Presidents. And it reminded me of my youthful interest in Colonial American history.

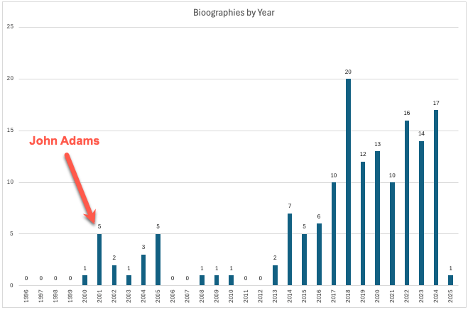

Prior to John Adams, I’d never really been interested in biographies, mainly due to lack of exposure. I went through the list of books I remember reading before I started keeping a list in 1996, and I couldn’t find any biographies on the list. That changed after reading John Adams. In 2000, I read Carl Sagan: A Life in the Cosmos by William Poundstone. This is the first biography (excluding memoirs and autobiographies) that appears on my reading list, and it took me over four years before I finally decided to read a biography. A year later, I read John Adams, and the avalanche began to build. Over the next quarter century, I read more than 150 biographies alone. The graph below illustrates the progression of this avalanche.

On the drive back to New York from Maine, I couldn’t stop thinking about the book. I was frantic to read another biography, one that was just as good. As I neared my destination, I passed by a mall where I saw a Barnes & Noble. I pulled off, went in and bought a copy of Truman by David McCullough. I figured I’d stick with McCullough for now since I enjoyed John Adams so much. Less than two weeks after I finished John Adams, I’d also zipped through Truman. I was hooked!

For a long time after reading John Adams, when someone asked me who my favorite president was, I’d answer without hesitation, John Adams. I clarify almost at once that I didn’t think he was the best president, just my favorite. There was a something about his character, his intelligence, and his integrity that impressed me. In recent years, John Adams has been dethroned as my favorite by his son, John Quincy Adams. I’ve now read more biographies of JQA than John Adams. For decades now, I’ve thought that the presidency was a role that was virtually impossible to prepare for. That said, if there was any one person who was “prepared” to be president, it was John Quincy Adams. By the time JQA was my age, he had served in the Massachusetts Senate, as a U.S. Senator for the state of Massachusetts, as Minister to the Netherlands, Minister to Prussia, Minister to Russia, Minister to the United Kingdom, and while at about my age was halfway through his term as Secretary of State. All of this before he became President. Then, after he served a term as President, he spent the next seventeen years in the House of Representatives.

John Adams also got me interested in the role of the President. Having devoured biographies of two presidents, back-to-back, I decided I should read at least one biography of every president. Like many of my reading adventures, I didn’t put a timeline on this, or even a plan. It would happen organically, but at some point I’d get there. I did impose a couple of rules: (1) the book had to be a presidential biography, not a memoir or autobiography; (2) I would shy away from those presidents who are still alive today. In the years since first reading John Adams, I’ve managed to read 51 biographies of 16 U.S. presidents, or about 35% of the total, ranging from George Washington to George W. Bush (the one exception to my rule #2):

#PresidentBooks1George Washington22John Adams53Thomas Jefferson84James Madison16John Quincy Adams316Abraham Lincoln318Ulysses S. Grant120James A. Garfield226Theodore Roosevelt632Franklin D. Roosevelt533Harry S. Truman234Dwight D. Eisenhower336Lyndon B. Johnson437Richard Nixon140Ronald Reagan243George W. Bush2John Adams also rekindled my interest in Colonial American history. From second to fifth grades, I lived in Warwick, Rhode Island and became engrossed in colonial history. Across the street from our house, and up a small hill was a graveyard surrounded by a stone wall that dated back to before the Revolution. Some of the graves had rusted markers that indicated military service in the Revolutionary War. We went on field trips to Boston, and Sturbridge Village, an old colonial town in Massachusetts. From the age of 7-1/2 to the age of 11-1/2 I was immersed in colonial history. John Adams reminded me of that history and I began to read more broadly about colonial history.

I’ve read McCullough’s John Adams three times, and I enjoy it more with each subsequent reading. There is a humble passage that has stuck with me ever since my first reading. It concerns Adams when he was still a young lawyer in Boston:

Long before, on his rounds of Boston as a young lawyer, Adams had often heard a man with a fine voice singing behind the door of an obscure house. One day, curious to know who “this cheerful mortal” might be, he had knocked at the door, to find a poor shoemaker with a large family living in a single room. Did he find it hard getting by, Adams had asked. “Sometimes,” the man said. Adams ordered a pair of shoes. “I had scarcely got out the door before he began to sing like a nightingale,” Adams remembered. “Which was the greatest philosopher? Epictetus or this shoemaker?” he would ask when telling the story.

I’ve thought about this passage every time I find myself wishing for better circumstance, seeing the grass greener over there. It has reminded me for decades to be happy with what I have, to enjoy it, to be moderate and abstemious.

Adams took the small things to heart and tried to appreciate them for what they were. After a winter storm damaged his trees, he wrote about the beauty of the scene, concluding with:

I have seen a Queen of France with eighteen millions of livres of diamonds upon her person and I declare that all the charms of her face and figure added to all the glitter of her jewels did not make an impression on me equal to that presented by every shrub. The whole world was glittering with precious stones.

McCullough shows that Adams was a complicated, but principled character. This book made such an impression on me when I first read it, that I feel an almost proprietary concern for the Adames. When I read in other histories and biographies, of contemporaries of Adams disparaging him, I am offended on his behalf, even though I recognize the flaws they point out. Adams made plenty of mistakes and took measures that I disagree with from my safe modern perch. But his character, intelligence, and integrity are what most impress about him. He served one term as president, but his legacy led to John Quincy Adams, another U.S. president, diplomat, and congressman; Charles Francis Adams, who was U.S. envoy to the United Kingdom for Abraham Lincoln; and Henry Adams, whose The Education of Henry Adams is the #1 book on Modern Library’s Top 100 Nonfiction Books of the Twentieth Century.

There are a handful of writers, now gone, that I wish would have written more. David McCullough was one of those writers. John Adams was my first exposure to his writing, but over the years, I managed to read every book he published, and all of them without exception were excellent. In an interview with McCullough late in his life, he said that he has a list of 20 or more projects that he wanted to work on. Since his death, I’ve often wondered if he had made enough progress on any of them to bring them close to completion. Would I see a posthumous McCullough book sometime in the future? It turns out the answer to this question is yes, I will. While performing a periodic search of forthcoming books, I discovered History Matters by David McCullough and edited by his daughter, Dorie McCullough Lawson. The book is described as a “posthumous collections of thought-provoking essays—many never published before… McCullough affirms the value of history, how we can be guided by its lessons, and the enduring legacy of American ideals.” The book is due out September 16, 2025. I’ve already pre-ordered it.

Did you enjoy this post?

If so, consider subscribing to the blog using the form below or clicking on the button below to follow the blog. And consider telling a friend about it. Already a reader or subscriber to the blog? Thanks for reading!