The December 6 Proclamation: A Call for Order Amidst Chaos

My research into the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862 began when I discovered that the Ho-Chunk, who lived on a reservation south of Mankato in 1862, were exiled from the state along with the Dakota in the spring of 1863. I wanted to understand why the Ho-Chunk, also known as the Winnebago, were banished despite not participating in the war. This led to my essay titled Unwarranted Expulsion: The Removal of the Winnebago Indians.

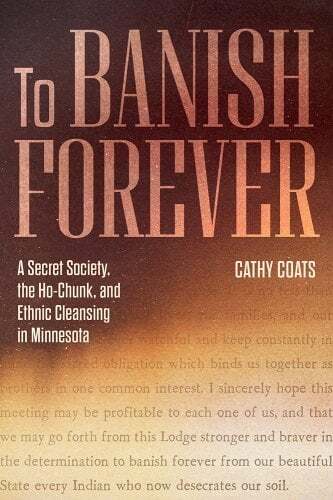

Recently, I was reminded of my research while reading To Banish Forever: A Secret Society, the Ho-Chunk, and Ethnic Cleansing in Minnesota by Cathy Coats. Coats provides excellent context for the Ho-Chunk removal and evidence explaining why it happened. I plan to explore Coats’ book further in a future post. For now, I want to share a startling piece of primary source evidence I was unaware of until reading her book.

After the U.S. – Dakota War, there was a strong call for harsh retribution against all Dakota people by the white settler-colonists in Minnesota. Henry Sibley and a military tribunal quickly charged and convicted 303 Dakotas of crimes they deemed worthy of execution. These sentences were sent to Major General John Pope in St. Paul, who forwarded them to President Lincoln in Washington, D.C., expecting swift approval. However, Lincoln did not act as quickly as the white citizens of Minnesota desired. Instead, he assigned two lawyers to review the cases before making a decision. Meanwhile, in Mankato, where the Dakota prisoners were held, threats of violence against them were rampant.

On December 4, 1862, the tension peaked when an angry mob marched to Camp Lincoln, the temporary Dakota prison. Reports indicate about 150 people, mostly unarmed, marched from New Ulm to Camp Lincoln but were stopped by the army. The crowd was loud but disorganized. All were taken prisoner and questioned by Stephen Miller, the Colonel overseeing the Dakota prisoners. They were released without incident, but the mere formation of the mob prompted a swift response from Governor Alexander Ramsey.

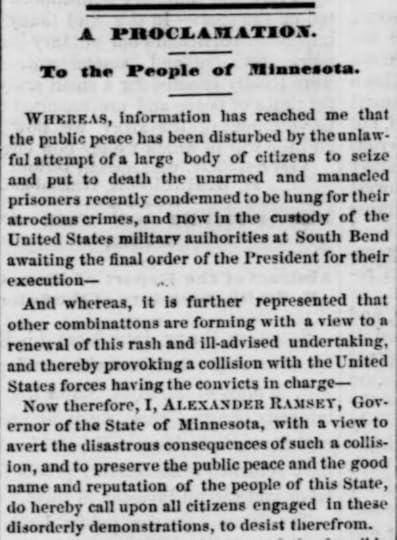

The response, dated December 6, 1862, and published in the St. Paul Daily Press on December 10, 1862, clearly reveals the fear, panic, and animosity in the community during that time. It is startling to read. I share it today to acknowledge and examine the reality of that era. It shows that while law and order were expected, retribution was foremost in the minds of Minnesota’s white citizens. This is evident in the line, “But whatever may be the decision of the President, it cannot deprive the people of Minnesota of their right to justice or exempt the guilty Indians from the doom they have incurred under our local laws.” Justice, as defined by the white settler-colonial population, would be served. I share the complete text with you now.

A Proclamation to the People of Minnesota

Whereas, information has reached me that the public peace has been disturbed by the unlawful attempt of a large body of citizens to seize and put to death the unarmed and manacled prisoners recently condemned to be hung for their atrocious crimes, and now in the custody of the United States military authorities at South Bend awaiting the final order of the President for their execution—

And whereas, it is further represented that other combinations are forming with a view to a renewal of this rush and ill-advised undertaking, and thereby provoking a collision with the United States forces having the convicts in charge—

Now therefore, I, Alexander Ramsey, Governor of the State of Minnesota, with a view to avert the disastrous consequences of such a collision, and to preserve the public peace and the good name and reputation of the people of this State, do hereby call upon all citizens engaged in these disorderly demonstrations, to desist therefrom.

The victims and the witnesses of the horrible outrages perpetrated by the savages may consider their sufferings and wrongs, a justification of this summary and high-handed method of retaliation. But the civilized world will not so regard it. Enlightened public opinion will everywhere condemn the vindictive slaughter of these guilty but helpless prisoners. The sober second thought of our own people will recoil from it with horror. The infatuated perpetrators of t will bitterly regret their ignominious share in the outrage which, if consummate, would inflict lasting disgrace upon themselves and the State.

Death, indeed, is the least atonement which these savage miscreants can make for their dreadful crimes. But the greater the crime the greater the need that its punishment should carry with it the weight and sanction of public authority.

It is not the blind fury of a mob to which Providence has entrusted the sword of public justice. The lawless violence which would anticipate the course of legal procedure by the massacre of these helpless prisoners in defiance of the authorities would deprive their punishment of all its legitimate effect.

Would it teach these savage men hereafter to respect the authority of a government thus openly condemned and degraded by an act of bold defiance on the part of its citizens.

Or, will it add to the sense of security of life on our frontier, to show that life is dependent on the will of an irresponsible mob?

Hitherto the conduct of our citizens in the midst of the extreme provocations which they have endured has been honorable to themselves and to the State.

The captured Sioux, instead of being indiscriminately slaughtered in the heat of passion as might have been expected, were conceded an impartial trial by a military tribunal. Those found guilty of capital crimes were condemned to death and now lay in durance awaiting the order of the President for their execution.

Our people indeed have had just reason to complain, of the tardiness of executive action in the premises, but they ought not to find some reason for forbearance in the absorbing cares which weigh upon the President.

The pressing and earnest representations repeatedly made of him from this Department of the necessity of proceeding promptly with the execution of the condemned Indians have been zealously sustained by the military and other authorities.

The Agent sent out by the Government gave the assurance upon his departure that he would spare no effort to procure an order to that effect. No official intimation has been received that the President contemplates any other course; and his final determination of the matter therefore soon be expected.

But whatever may be the decision of the President, it cannot deprive the people of Minnesota of their right to justice or exempt the guilty Indians from the doom they have incurred under our local laws. If he should decline to punish them the case will then clearly come within the jurisdiction of our civil courts. In a month the State Legislature will assemble and to them it may be safely left to provide for the emergency.

I appeal then to the good sense of the people to await patiently and peacefully the due course of law. I entreat them not to throw away the good name which Minnesota has hitherto sustained by a rash act of lawlessness which is neither necessary to the ends of justice, of personal security or even of private vengeance; but which would be subversive of public order and a perpetual stigma upon the community.

I entreat them as good citizens having at heart the public welfare not to add the injury which our young State has already sustained at home and abroad from its exposure to savage violence the worse and more permanent injury which it would suffer in the estimation of the world from the spectacle of barbarous violence among our own citizens.

Given under my hand and the Grand Seal of the State, at the city of St. Paul, this sixth day of December, A.D. 1862

Alexander Ramsey

Sources:

The Dakota Conflict Trials: An Account, UMKC School of Law, https://famous-trials.com/dakotaconflict/1525-dak-account

St. Paul Daily Press, December 10, 1862, https://archive.org/details/sep2186215thes/page/n3/mode/2up

A History of the Great Massacre by the Sioux Indians, in Minnesota Including the Personal Narratives of Many who Escaped by Charles S. Bryant and Abel B. Murch, https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_History_of_the_Great_Massacre_by_the_S/zwCyX5zkHeoC?hl=en&gbpv=0

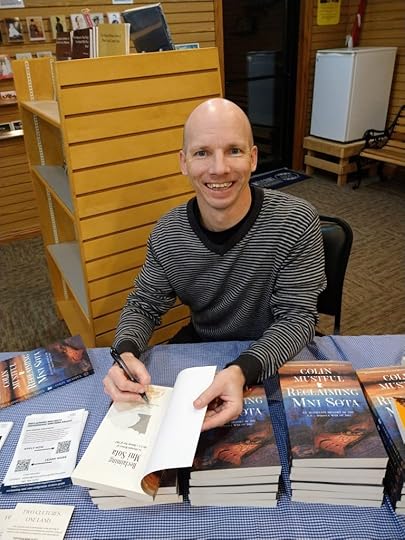

Colin Mustful is a celebrated author and historian whose novel Reclaiming Mni Sota won the Midwest Book Award for Literary/Contemporary/Historical Fiction. With a Master of Arts in history and a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing, Mustful has penned five historical novels that delve into the complex eras of settler-colonialism and Native American displacement. He is also the founder and editor of History Through Fiction, an independent press dedicated to publishing historical narratives rooted in factual events and characters. Committed to bringing significant historical tales to light, Mustful collaborates with authors as a traditional and hybrid publisher. Residing in Minneapolis, Minnesota, he enjoys running, playing soccer, and believes deeply in the power of understanding history to shape a just and sustainable future.