Turning words into art

“I would go from one city to the next, inspired by the monks in the Middle Ages, who would carry knowledge from one monastery to the next monastery.” Hans-Ulrich Obrist, Swiss art curator, critic, and art historian; artistic director at the Serpentine Galleries, London.

What to do when your mother-in-law states that she has one more trip she’d like to go on: to England with her son and you?

It was a request that came out of the blue, while we were being transported from the airport in Los Angeles to the house of friends in Santa Monica. We’d actually asked her to come to England with us years before, but she’d always found an excuse not to go.

But she’d made this statement in front of several people, so when we took her up on it, she had no excuse to fall back on. I began planning out a trip I thought she’d enjoy, and then she said, “You know, I’ve heard that it’s really easy to go from London to Paris. Could we go to Paris for a day?”

Well, we decided to make the trip ‘a tale of two cities’: four days in London, then the Chunnel Train to Paris for another four days.

We had a blast. She was in her early 70s at that time, but we’d already travelled with my mother, so we knew how to pace things. I planned a mix of sights and activities, and one of them was just walking around each city to get to know it intimately.

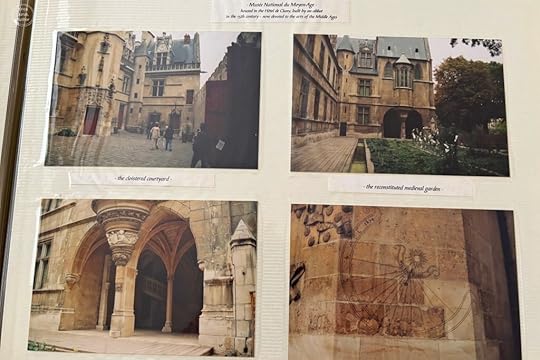

We stayed in the Latin Quarter in Paris, at a very atmospheric boutique hotel situated beautifully amidst all kinds of sights, and just down the street we came across the Cluny Museum of the Middle Ages. It’s a wonderful place, filled with treasures, including illuminated manuscripts, and that’s where my fascination with them took hold. I even bought a quite large book about them in the gift shop and lugged it all the way home.

Photos of the exterior of the Cluny Museum from our trip, by E. Jurus, Author, all rights reserved

Photos of the exterior of the Cluny Museum from our trip, by E. Jurus, Author, all rights reservedWhen I was fleshing out the heroine of my Chaos Roads trilogy, Romy Ussher, I knew that she had to be an archivist, with the same intense interest in preserving knowledge as her patron, the Egyptian god Thoth. And it was a natural fit that she’d specialize in illuminated manuscripts.

Illuminated manuscripts are gorgeous works of art, which monks began toiling over as early as the 6th century. The monks lit up the ‘Dark Ages’ with the beauty of their work, turning simple pages of text into rich collections of imagery at a time when books were scarce and incredibly valuable, taking hours and hours of hand-writing and painting by candle light.

Manuscripts are so named from two words from Latin: manus, or hand, and scriptus, or writing. Centuries before the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg, making copies of books like the Bible for churches and monasteries to use required laborious copying, letter by letter, with ink and a quill pen, in the elaborate scripts of the time period. It was painstaking work – no ‘back’ button or ‘undo’ to fix errors.

Then, designated artists would paint in small, intricate decorations, adding ornate capital letters, elaborate borders, and painted scenes called miniatures. The illustrations were meant to guide readers through the text, which was critical during medieval times when many people didn’t know how to read.

The word “illuminated” was also taken from Latin: illuminare, meaning ‘lighted up’. And it actually referred to being decorated with gold, applied in the form of gold leaf.

Section of an illuminated ms showing the gold leaf – Source: Byzantium Constantinople 11th century – Gospel Book with Commentaries – 1942.152 – Cleveland Museum of Art, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=77629894

Section of an illuminated ms showing the gold leaf – Source: Byzantium Constantinople 11th century – Gospel Book with Commentaries – 1942.152 – Cleveland Museum of Art, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=77629894 Churches used these beautiful manuscripts for delivering the liturgy, as well as for the daily devotions of their community, from the monks to nuns and laypeople. Special forms of manuscripts, like Psalters and Books of Hours, were meant to inspire devotion to God. Monasteries and churches would have a collection manuscripts to share among parishioners for their daily prayers.

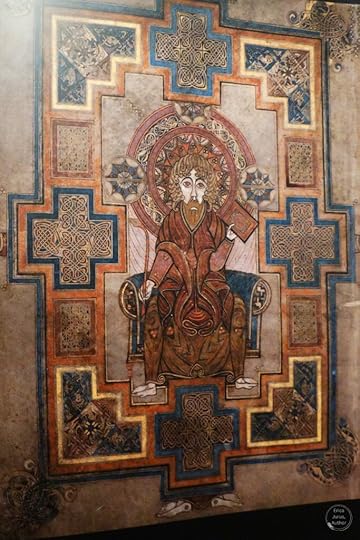

Perhaps the most famous illuminated manuscript is the magnificent Book of Kells, one of Ireland’s national treasures. Its actual origin is unknown, but it was held in the Abbey of Kells for centuries. There were likely several contributors from various monasteries in or around 800 AD, and contains the four Gospels of the New Testament. What’s left of it today, after some mistreatment over the course of its life, comprises 340 leaves of text written in ‘iron gall’ ink, extracted from the galls of oak and other trees, and incredible decorations with paints sourced from distant lands. It was clearly a valuable item, to have so much thought and effort put into its making. You can see it in the Library at Trinity College in Dublin, Ireland, and although photos of it aren’t allowed, there’s also a large gallery display explaining what the illustrations mean.

Section of the Book of Kells, from the gallery display at Trinity College, Dublin Ireland – by E. Jurus, Author, all rights reserved

Section of the Book of Kells, from the gallery display at Trinity College, Dublin Ireland – by E. Jurus, Author, all rights reservedIn my novels, Brother Domitian, who entered Penmon Priory in Wales at a young age, displayed a gift for illustration and became the main illustrator there before the Dissolution of the Monasteries in England by Henry VIII in 1536.

By the 14th century, a growing, educated middle class in Europe began requesting illuminated manuscripts for their private collections, particularly among the aristocracy. These books were often displayed in private libraries and then passed on as heirlooms.

Ironically, Henry VIII himself commissioned an illuminated Psalter, which contained Psalms and other devotional texts to be recited during the week for morning and evening prayers. He obtained it from a French illustrator, to show Henry performing in various capacities, from slaying Goliath to posing as a penitent (which was doubtful in real life). It can be seen in the British Library, including on their Digitised Manuscripts and Virtual Books websites.

One of the folios (leaves) from Henry VIII’s Psalter, showing him reading – Source: British Library, By Medieval scribe and illuminator – British Library [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17319921

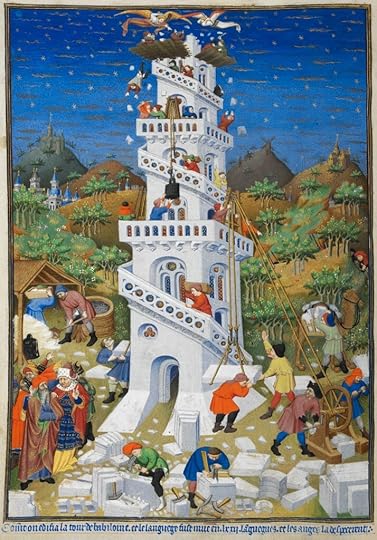

One of the folios (leaves) from Henry VIII’s Psalter, showing him reading – Source: British Library, By Medieval scribe and illuminator – British Library [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17319921Other types of illuminated manuscripts included the Antiphoner, a volume of music (hymns, prayers, etc.) used by all churches and monasteries for daily religious services; the Missal, used by a priest to conduce Mass and still in use to this day; the Breviary, containing hymns and readings for morning and evening prayer outside of Mass; and the Book of Hours, for personal use, so called because the cycle of prayer handed down from monastic life divided the day into eight segments or “hours” to conduct daily devotions in. The Book of Hours also included a calendar, listing major feast days of the church year.

Bedford Hours; building the Tower of Babel, By Bedford Master – This file has been provided by the British Library from its digital collections. It is also made available on a British Library website. Catalogue entry: Add MS 18850, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23030937

Bedford Hours; building the Tower of Babel, By Bedford Master – This file has been provided by the British Library from its digital collections. It is also made available on a British Library website. Catalogue entry: Add MS 18850, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23030937Books of Hours were meant for anyone who could read, and became immensely popular because of their wonderful illuminations. They became status symbols, and families who’d never owned a book would pool their resources and by one. Books of Hours were the early best-sellers of the book world.

The field of Illuminated Manuscripts is too large for one blog post. Perhaps I’ll put together an entire document about it for special access one day. In the meantime, if you’re heading for a museum soon, do check out any mss (short-form plural for ‘manuscript’ for those ‘in the know’  ) they may have and enjoy their artistry in person.

) they may have and enjoy their artistry in person.

Mom-in-law Jenny and me (L,R in this pic) in Montmartre, overlooking the city of Paris; some damage (blurring) in the lower part of the photo – by Erica Jurus, Author, all rights reserved.

Mom-in-law Jenny and me (L,R in this pic) in Montmartre, overlooking the city of Paris; some damage (blurring) in the lower part of the photo – by Erica Jurus, Author, all rights reserved.