The India of Today and Yesterday

AuthorPradeep Damodaran travelled to many cities and towns associated with thefreedom movement. He wanted to get a feel of whether the history stillresonates. He also focused on the daily life of the people.

ByShevlin Sebastian

InFebruary 2022, author Pradeep Damodaran visited the Sabarmati Ashram inAhmedabad. Expectedly, there were plenty of visitors, ranging from the young tothe old. Pradeep checked out Hriday Kunj, the home of Mahatma Gandhi andKasturba, between 1918 and 1930. He also walked through the museums and photogalleries.

WhenPradeep perused the visitor’s book, he got a surprise.

Onevisitor wrote that Gandhi would rot in hell for what he did to all Indians.‘Even after 75 years of Independence, still we are crying, dying because ofyou, Mr. Gandhi. I realised why BABASAHEB B.R. AMBEDKAR did not call youMahatma. Because of you, more than one crore people died during partition. Onlysoldiers dead in Kashmir as of today’s count is 90,000!’ Pradeep added inbrackets: ‘No idea how he arrived at this figure.’

Whenhe pointed this out to Atul Pandya, director of the Sabarmati AshramPreservation and Memorial Trust, he said that this freedom to criticise Gandhiwas exactly what the man had fought for. ‘Let them try to openly criticisetoday’s leaders and see if they can get away with that,’ said Atul

Pradeepwent to Juhapura, the Muslim ghetto in Ahmedabad and the Gulbarg Society inChamanpura.

Thisis how he described what he saw at the Gulbarg Society where 69 people,including women and children, were hacked to death by rioters in 2002: ‘Aneerie silence engulfed us. The entire gated community was desolate andlifeless… At the entrance, to my right, were sprawling two-storey homes withspacious balconies, porticos with round pillars and tiled flooring completelyblanketed by dust, soot and scars of burnt human flesh and blood. Doors andwindows had been ripped off, probably stolen by anti-socials. Fans andfurniture in areas not destroyed by the fire were also missing. Spacious livingrooms and bedrooms were bereft of furniture; burnt clothes and glass pieces layscattered upon piles of other debris, mostly burntwood.’

Hemet Rafiq Qasim Mansoori, who was wearing sunglasses. Asked whether he had beenpresent during the massacre, Rafiq took off his sunglasses. His right eyelooked completely smashed. ‘A stone hit me in the eye,’ he said, by way ofexplanation about what happened to him during the attack. ‘I lost nineteenfamily members that day and that included my wife and infant son.’

InGodhra, Pradeep dwells on the long history of communalism in the town, whichwas a revelation. Muslims in Godhra belonged to the Ghanchis branch. They weremostly poor and uneducated.

DuringPartition, many Sindhis, belonging to the Bhaiband sect, migrated from Karachiand settled near Godhra. They had experienced horrendous suffering at the handsof the Muslims in 1947. That memory remained strong. The Hindu communaliststook advantage of this resentment.

Thefirst large-scale communal riot took place in 1948 between the Sindhis and theGhanchis. The Sindhis burned down over 3500 properties belonging to theGhanchis. They had to flee. The Sindhis took over the lands. ‘Even at thattime, arson was the top choice for rioters in this region,’ wrote Pradeep. Theriots between the two communities have continued intermittently over thedecades.

Atone time, Pradeep went to interview Maulana Iqbal Hussain Bokda, the principalof the Polan Bazar Urdu School. When the Maulana spoke about the socialisolation and economic backwardness of Muslims, Pradeep asked whether theMaulana had regretted not emigrating to Pakistan.

Adisturbed Bokda led Pradeep down a corridor and pointed, through a window, atthe tricolour flying high outside. ‘You see that tiranga? Since 2005, the flaghas been hoisted every day at 7 a.m. and is brought down at 5 p.m.,’ saidBokda. ‘You tell me if you can find this anywhere in India. The tiranga ishoisted every single day! If one person cannot do it, someone else does. Youknow why? It is because we are Indians and we believe in this country.’

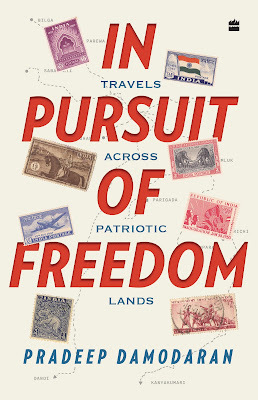

Allthese stories are recounted in the book, ‘In Pursuit of Freedom — TravelsAcross Patriotic Lands’. Pradeep would go to a particular place, which had somelink with the freedom movement. There, he would describe his encounters withthe local people. Then he would delve into the history of the place, asconnected to the freedom movement.

So,in Bardoli, he talked about the Bardoli Satyagraha against the British byfarmers against high land taxes in 1928. Its success resonated across India.The concept of nonviolent resistance became an idea that nobody could resist.And it led to the independence of India, although it took another twodecades.

Inthe first section, Pradeep goes to different places in Gujarat. In Part 2, hegoes to Uttar Pradesh. His first stop is Jhansi. Pradeep wanted to find outwhether the residents still remembered Rani Lakshmibhai.

Andyes, she is very much alive through hoardings, government flex boards and namesof colleges and other institutions. He visited the Jhansi Fort and marvelled atits construction.

Whilein Jhansi, Pradeep had an unusual experience. People would often ask him whichreligion he belonged to. They would feel unnerved when Pradeep said he was anatheist.

Henoted that those who asked this question had ‘never moved out of their nativetowns and villages for generations. They had been fed stories about thegrandeur and courage associated with their religion. Merely seventy-five yearsof imposed secularism are, perhaps, hardly sufficient to erase over 1000 yearsof religious devotion, as I could see first-hand,’ writesPradeep.

InPala Pahadi village, Pradeep heard a familiar nationwide lament echoed by a villager:‘What is there to say? Can’t you see for yourself? Everything is rotting here;nothing has changed in the past seventy-five years. We have no roads, nodrinking water, nor any form of sanitation. Where are the free toilets? Whereare the schemes the government has announced? We have got nothing.’

InNandulan Khera, the people had converted over 90 percent of the Swachh Bharattoilets into storerooms for storing hay and other non-essential stuff. Theproblem with the toilets was that the government had not installed a septictank. And for the few who built septic tanks, once it got full, no lorriescould come to their village to get it emptied because of a lack of properroads. So the people stopped using the toilets and went back to the fields for theirablutions.

InUnnao, Pradeep went to the village of Mankhi, 17 kms away. He wanted to meetthe girl, whom ex-BJP MLA Kuldeep Singh Sengar raped on June 4, 2017, tonational outrage. Later, her father died in police custody. Pradeep discoveredthat because of the danger to their lives, the family no longer lived in thevillage. They had moved to Unnao.

Backin Unnao, Pradeep met the girl’s mother, Asha Singh, a Congress candidate forthe UP Assembly elections. She detailed the sequence of events that took place.Asha bemoaned the fact that men continued to rape women, especially of thelower castes, with impunity. All the publicity associated with her daughter’scase had changed nothing. The caste system remained powerfully rooted inpeople’s minds.

Standingnext to Asha was a young woman who looked confident and sophisticated. It wasmuch later that Pradeep came to know she was the victim. ‘She was definitelysmart; perhaps in a decade or so, she would be ready for the polls and Unnaomight then have a serious contender from the fairer sex,’ saidPradeep.

Someof the other places Pradeep visited included Chauri Chaura, Champaran, andMotihari.

Inthe third section, Pradeep goes to Punjab, where he focuses on the Ghadarmovement. These were expatriate Indians, mostly Punjabis, who fought tooverturn British rule in India. He also visited Don Parewa (Nainital), Tamluk(Bengal), Tentuligumma (Odisha), Panchalankurichi and Idinthakarai (Tamil Nadu)

Thisis an eye-opening book. It is a history lesson and a picture of modern-dayIndia. This history, told as truthfully as possible, is important especiallywhen there is a lot of rewriting and erasure taking place these days. Forexample, the National Council of Educational Research and Training has removedall chapters on the history of the Mughals and of Gandhi’s opposition to Hindunationalism.

Thebook shows that while progress has been made, in many areas, things have stayedthe same just as they were one hundred years ago. But the people fight on. Thereis a deep sense of frustration and anger at the government because of the lackof jobs for the young and for its failure to provide basic services. In theend, this book is an insightful addition to help us better understand the Indiaof today and yesterday.

(Ashorter version was published in the Sunday Magazine, The Hindustan Times)