Defending and Defining Words of Wisdom

Defending and Defining Words of Wisdom | Carl E. Olson | Catholic World Report

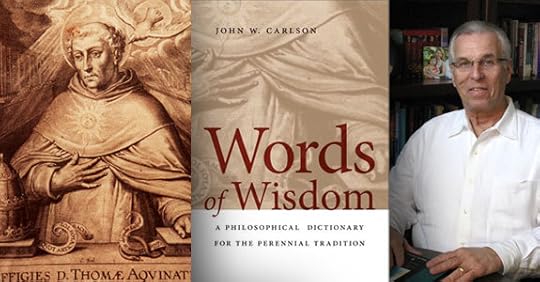

John W. Carlson’s new philosophical dictionary is an impressive and valuable work of scholarship inspired by love of wisdom, St. Thomas, and Bl. John Paul II.

Dr. John W. Carlson is a professor of philosophy at Creighton University. He is the author of Understanding Our Being: Introduction to Speculative Philosophy in the Perennial Tradition and the recently published Words of Wisdom: A Philosophical Dictionary for the Perennial Tradition (Notre Dame, 2012). He was recently interviewed by Carl E. Olson, editor of Catholic World Report, about the importance of philosophy, Blessed John Paul II’s encyclical Fides et Ratio (1998), and the reason he penned a dictionary with 1,173 entries.

CWR: Let’s begin with a Big Picture question: what is the state of philosophy today? I ask because philosophy today seems to be dismissed often by certain self-appointed critics. For example, the physicist (and atheist) Lawrence Krauss, author of A Universe from Nothing, said in an interview with The Atlantic that philosophy no longer has “content,” indeed, that “philosophy is a field that, unfortunately, reminds me of that old Woody Allen joke, ‘Those that can’t do, teach, and those that can’t teach, teach gym.’” Why this sort of antagonism toward philosophy?

Dr. Carlson: So Krauss in a single sentence denigrates both philosophy and gymnasium. May we begin by remarking that Plato—who thought highly of both—would not be impressed?

Your question, of course, is a good one. A response to it requires noting salient features of Western intellectual culture, as well as key concerns of philosophers in the recent past. Over the last century and a half, our culture has come to be dominated by the natural or empirical sciences and technological advances made possible by their means. It thus is not surprising that there has arisen in various quarters a view that can be characterized as “scientism”—i.e., one according to which all legitimate cognitive pursuits should follow the methods of the modern sciences. Now, somewhat ironically, this view is not itself a scientific one. Rather, it can be recognized as essentially philosophical; that is, it expresses a general account of the nature and limits of human knowledge. But if it indeed is philosophical, we might well ask on what basis scientism is to be recommended. Does this view adequately reflect the variety of ways in which reality can be known? To say the least, it is not obvious that the answer to this question is “Yes.”

A second factor contributing to the idea that philosophy has no specific content is the following: throughout much of the 20th century, a principal focus for many thinkers—whether pragmatists, process philosophers, linguistic analysts, phenomenologists, or, for that matter, followers of St. Thomas Aquinas—was the question of philosophical method. Today, however, philosophers of virtually every school once again are taking up substantive issues. (Professor Krauss apparently did not get the memo.) It may be added that, throughout the century, Thomist thinkers continued to treat, in addition to methodological issues, questions of philosophical substance—e.g., questions about the nature and “principles” of being, about the defining characteristics of the human good, etc. Needless to say, their approach to these topics was not, in the strict sense, empirical. But as a leading 20th century Thomist, Yves R. Simon, once remarked: “Let genuine scientists read our [philosophical] works; they will see we are kindred spirits.”

I would hope that this statement applies as well to the accounts in Words of Wisdom.

CWR: Turning to the realm of Catholic philosophy and belief: Blessed John Paul II’s encyclical Fides et Ratio (1998) met with criticism and even derision from certain Catholic intellectuals. Why was this? And how is it that the encyclical had such an important impact on you and other philosophers?

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers