The mysterious hole in the wall inside a beautiful 19th century Stuyvesant Square church

Since the 1850s, St. George’s Episcopal Church has stood majestically over Stuyvesant Square, a welcoming Romanesque castle in a pretty enclave defined by its namesake park—which was developed only a decade before the church arrived.

Now part of the Parish of Calvary-St. George, the church has a storied history going back to the 1750s. It got its start as a chapel on Beekman and Cliff Streets serving East Side residents who couldn’t make the trip to Broadway to Trinity Church, the city’s main Episcopalian church, per a 1975 report from the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

After separating from Trinity Church, the congregation grew, and in 1856 the current church was completed. Old-money New Yorkers made up the congregation in its early decades. But after the interior and roof were rebuilt following a devastating 1865 fire, an increasing number of German immigrants made it their parish into the 20th century.

The stained-glass windows, wooden pews, cavernous nave, and elegant carved wood pulpit make the interior feel commanding and sacred. But there’s something else inside the church worth calling out, and it can be found on a wall toward the back.

It’s a tiny hole—a bullet hole. But why would a bullet hole be inside St. George’s?

The answer has to do with one of the church’s most prominent parishioners, J. P. Morgan. The financier worshipped at St. George’s for decades; he served as a wardsman of the church and was instrumental in supporting social programs for the local immigrant community.

When Morgan died in 1913, his funeral, held at St. George’s, packed the church pews and attracted a huge crowd of onlookers outside Stuyvesant Square, according to the New York Times.

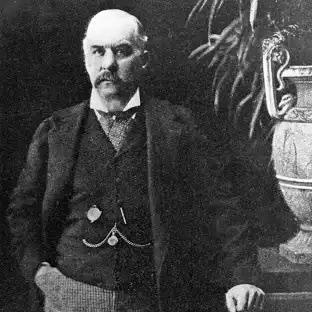

Though Morgan (at right, in 1890) gave generously to St. George’s and his philanthropy benefited many other organizations and causes, he had many detractors. One was a man named Thomas W. Simpkin.

There’s no evidence that Simpkin, a London-born printer described in another New York Times article as “a lunatic, recently escaped from an asylum,” had ever met Morgan. But that didn’t stop him from showing up at St. George’s on April 18, 1920 with a gun and plans to shoot Morgan—even though Morgan had been dead for seven years.

During services that morning, Simpkin “fired several shots,” according to Susie J. Pak, author of Gentlemen Bankers: The World of J.P. Morgan, killing “Dr. James Markoe, a close friend of the Morgan family.” Markoe had been passing a collection basket just before he was hit.

Markoe was brought to the Lying-In Hospital on Rutherford Place (which Morgan had funded two decades earlier), where he died. Simpkin, quickly apprehended, admitted that he “came to get Morgan,” per the New York Tribune on May 4, and that he did not know Morgan was already dead.

The New York Times article from April 19 states that Simpkin “drew a revolver and shot Dr. Markoe in the eye. He then fired another shot which lodged somewhere in the walls of the church.”

Accounts of the bullet still lodged in the wall have circulated online for some time. I wanted to see if it existed, and a friendly person affiliated with the church pointed the hole out to me. No bullet, just a bullet hole.

There’s a lot more to St. George’s besides a tragic murder in the middle of a Sunday service a century ago. And there’s a lot more to J.P. Morgan besides his detractors.

On Thursday, January 23, American Ancestors fine art curator Curt DiCamillo will be giving an afternoon talk at the Colony Club on Park Avenue titled “J.P. Morgan: Banker, Collector, Renaissance Prince” with a focus on Morgan as a collector of exquisite art and artifacts. Visit this link for more information and registration info to attend.

[Third image: Wikipedia; fourth image: NYPL Digital Collections]