The Articles of Dragon: "The Chivalrous Cavalier"

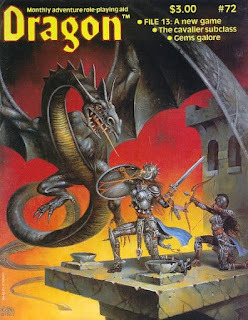

From the moment Gary Gygax first announced that his upcoming revision to Advanced Dungeons & Dragons would include, among other additions, a collection of new character classes, my younger self was waiting with eager anticipation for any news about what these classes might be or what abilities they might possess. By the time issue #72 of Dragon (April 1983) had come out, Gygax had already presented previews of two of these new classes, the barbarian and the thief-acrobat, neither of which thrilled me. I didn't hate either of them, but I didn't see much scope for their use in my ongoing AD&D campaign at the time – and neither did my players, who largely ignored them a brief flurry of interest.

From the moment Gary Gygax first announced that his upcoming revision to Advanced Dungeons & Dragons would include, among other additions, a collection of new character classes, my younger self was waiting with eager anticipation for any news about what these classes might be or what abilities they might possess. By the time issue #72 of Dragon (April 1983) had come out, Gygax had already presented previews of two of these new classes, the barbarian and the thief-acrobat, neither of which thrilled me. I didn't hate either of them, but I didn't see much scope for their use in my ongoing AD&D campaign at the time – and neither did my players, who largely ignored them a brief flurry of interest.This issue offered readers a third proposed class: the cavalier. Described as a "sub-class of fighter ... in service to some deity, noble, order, or special cause," the cavalier was basically a knight, drawing on both historical orders of knighthood and those from legend and literature. Much like the paladin, with whom it shares many similarities (more on that soon), the cavalier has hefty ability score requirements for entrance (STR, DEX, and CON 15+, INT and WIS 10+), as well as belonging to the right social class. A cavalier must initially be good in alignment, whether lawful, chaotic, or neutral, though he may shift away from goodness before 4th level without penalty, which I always thought was an odd detail.

Unlike the paladin, which is a human-only class, the cavalier admits humans, elves, and half-elves, all of whom have the potential for unlimited advancement. The class is focused on mounted combat, which, while appropriate based on its inspirations, would seem to limit its utility in dungeon-focused adventures. No matter: cavalier get numerous other useful abilities, such as combat parries, improved saves against fear, impressive starting equipment (a consequence of their high station), weapon specialization, and, perhaps most remarkable of all, ability improvement. Every time a cavalier gains a level, he rolls 2d10 and adds the result as a note after his Strength, Dexterity, and Constitution scores. When the total from these rolls reaches 100 for any ability, it increases by 1 point.

Needless to say, the cavalier was quite a popular class among my friends and I at the time issue #72 appeared. I'd long been seeking an "official" AD&D knight class, so the cavalier scratched a longstanding itch of mine. That the class Gygax presented was also incredibly potent, possessing multiple powerful abilities, was just icing on the cake. Compared to the fighter, of which it was a sub-class, the cavalier was just better in almost every way, especially, if as was usually the case, one were not too strict about the rolling of ability scores for new characters. Consequently, I saw a lot of cavalier characters for a while, both in my own games and in those of friends. I can't say I really blamed anyone for this, in light of the class's power. Plus, it had the imprimatur of Gary Gygax, so who could argue against its inclusion?

Over time, quite a lot of us fell out of love with the cavalier. The truth was that, as presented here – and, later, in Unearthed Arcana – the class was simply out of whack with those in the Players Handbook. Perhaps, I thought, once Gygax completed his full revision of AD&D, it might be more in line with the overall power level of the game, but, until then, it was simply too much. This was doubly true of cavalier-paladins, which combined the abilities of both classes – what was Gygax thinking? Yes, it's true that there were various social restrictions placed on cavaliers through their code of honor that might, in principle, keep them in line, but, as kids, that was rarely sufficient to rein them in. I soon forbade cavaliers from my games and hardly anyone complained about it.

Looking back on this article now, it's pretty clear that, by 1983, Gygax's conception of AD&D was in the process of shifting considerably from his original vision. On some level, I can't really blame him. By this time, he'd been playing some version of D&D for over a decade, so it was probably inevitable that he'd want to do something different than he'd done before. Everything he was writing around this time suggests that he was becoming increasingly interested in a more high-powered kind of fantasy, one whose characters were personally powerful and whose adventures involved high stakes and equally powerful foes. Again, I cannot blame him for this. Having refereed my House of Worms campaign for a similar length of time, I know only too well the temptations of going Big, sometimes to the detriment of the game itself.

That's more or less how I look at the cavalier and most of the Gygax-penned material that first appeared in Dragon and later in Unearthed Arcana: experiments gone wrong. Many of them seemed like better ideas than they turned out to be. "Even Homer nods," as the saying goes, and so it was with Gygax and the cavalier.

James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers