301AD Christian Missions History Musings (CMHM). Century that Changed So Much

In 301 AD, Christianity first became a state religion. (I know that legend has it that Osrhoene established Christianity as its state religion in the 2nd century… but even if true, that was only for a short time.) In 301AD, Armenia became a “Christian nation.” Eleven years later, with the Battle of Milvian Bridge, Christianity mainstreamed in the Roman Empire, and gained status as the favored religion, except during the reign of Julian the Philosopher (or Apostate if you prefer), until it became the state religion of the Empire in 381AD.

Being the state religion could be considered the “ideal” for participants in a particular faith. Being part of the state religion means one moves from being persecuted (to perhaps become the persecutor). Being part of the state religion means that the power that was in the hands of other people starts to flow to the leadership of one’s own faith. Being part of the state religion means that one’s religion often starts to become more attractive to outsiders (because of the change regarding persecution and power).

However, while many faiths are pretty comfortable with with this status. Christianity struggles at this because, from its foundation, the Christian faith was a religion of powerlessness. It idealizes servanthood and humility. However, the bishops of churches in the Roman Empire seemed to be quite comfortable embracing the new status. Eusebius of Antioch clearly expressed appreciation for Emperor Constantine and his self-described role of “bishop of bishops.” People can (and do) argue about whether this transition to Imperial Church was a good thing or bad thing. As a Baptist I am pretty firmly on the side of it being a bad thing (even though there are some Baptists today that appear enthralled at the possibility of state power). That being said, I am trying to focus on church history in terms of missions, not denominationalism. So how did this transition affect missions?

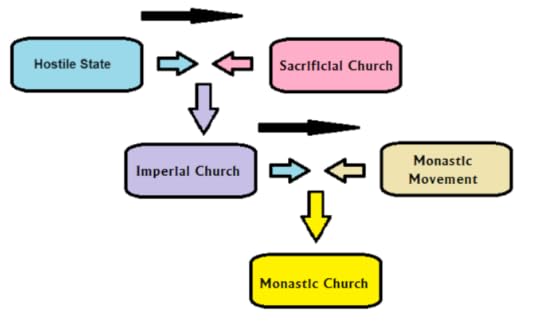

As noted in the figure above, there was a dialectic process going on. A hostile empire helped create a church that was persecuted, sacrificial, and populated by the deeply committed to their faith. The church was generally small but mighty. Overtime, the small and mighty church clashed with the hostile empire leading to an empire that was pro-Christian— leading to an Imperial church. This led to a popularization of Christianity that ended up “watering it down.” Living in the United States and in the Philippines, I still see a lot of social Christians— joining the church because of social connections rather than a faith that endures persecution. This has led in the United States, Philippines, and the 4th century Roman Empire, churches whose make-up (in terms of virtues and morality) is little discernible from the broader society.

In the Roman Empire, this “corruption” of the now popular church led to people being dissatisfied. Many of these separated themselves away, living a monastic life. Over time this style of living became corporate as these people joined together in faithful living and common purpose. This monastic movement was, in essence, a sodality structure, separate from the modality structure of the church. Later on, the monastic movement became less an exodus from the church, and more like a tool to revitalize the church and carry out specific works of the church (becoming in some sense, a monastic church).

From a missional standpoint, this century had mixed effects:

Positively, the transition to state church helped the church grow in size— rapidly.Negatively, the transition led to a church that had much less of a moral witness to the community… undermining its missional impact.Negatively, being a the religion of a state means that for surrounding nations and territories, Christianity becomes the “faith of the enemy.” This, potentially, undermines its international or cross-cultural impact. Positively, the monastic movement that developed in response to the changes going on in the church, eventually led to structures that were focused on missions. Missionary monastic orders became one of the greatest structures for mission work in church history.One final thing— the transition of a religion to a state religion leads to some greater level of identification between the religion and the people. From 301AD until now, Armenia identifies with Christianity even when ruled by Muslims and by Atheists. Much of the lands of the former Roman Empire identify deeply with their Christian heritage. Is this a good thing? Perhaps… or perhaps not. Is cultural Christianity a good thing? I truly don’t know. It feels like a good thing in comparison to when living under a hostile regime or faith. The church, however, has often been at its best in such hostile conditions.

So was the fourth century good for the missional church? Probably overall the answer is “Yes.” The growth of the monastic orders in the Eastern and Western churches have positively impacted missions even down to the present. But an argument could easily be made that the worst thing to happen to the church. Popularity, is not always a good thing.