Between Paris and Williamsburg: I Am Forbidden, by Anouk Markovits

Originally posted on Unpious.net.

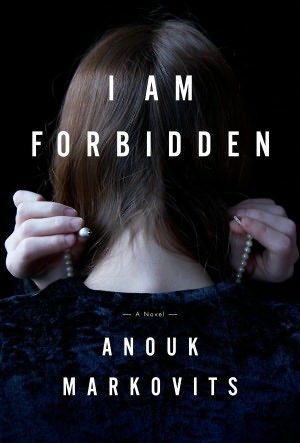

I Am Forbidden

By: Anouk Markovits

Hogarth, 320 pages

A man runs naked to the Aron Kodesh. A boy, after witnessing the slaughter of his family by the Romanian Iron Guard, is saved, to be raised as a Christian. In parallel: The Satmar Rebbe, in an open car, is within shouting distance of his Hasidim whom he does not or cannot save from extermination. This is national tragedy, theological failure.

It is the year 1939, in Maramures, Transylvania. 5-year-old Josef, his skullcap gone, his golden sidecurls shorn, is being raised by Fiorina, his family’s Christian maid. He has almost forgotten his Jewish origins when, several years later, he rescues a girl, Mila, whose parents are killed as they run to the Satmar Rebbe, whom they glimpse in an open train car. The rebbe will save them, they think, but instead the woman is shot; the man, still wearing his tefillin, is beaten to death in the town square. The Satmar rebbe, meanwhile, with aid from the Zionists, is on his way to safety in Switzerland.

Josef directs Mila to the home of a Satmar scholar, Zalman Stern, who later comes to retrieve Josef from his adoptive Christian mother and sends him on to yeshiva in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. The Sterns settle in Paris, and Mila remains with them, raised as a daughter — and as a sister to another girl, Atara. The two girls share everything at first but follow very different paths, both eventually intertwined with Josef’s: Mila is drawn to religious fervor, messianic redemption, and Bible study, while Atara asks herself, at first tentatively, if it is selfish to live and think as she wishes.

Despite the story’s foundation in tragedy and religion, this is not a Chaim Potok book full of disputation. We are face-to-face with people and the structures they create to deny death, bring the Messiah, or understand loss. When Josef is retrieved by Stern back to the Jewish world from Fiorina’s protection, we are given to understand the small tragedy they both live through in the shadow of a larger one, sharing a moment of “losing all, of having already lost”–a moment a lesser writer would have overlooked.

The inner lives of the punctiliously Orthodox, with their suppressed desire, menstrual obsession, and fear of death, coexist in the same book (and sometimes on the same page) as the deep joy and brilliant light of communal celebrations and Torah study. We feel the desire for Messiah in Mila, as we are moved by Atara’s yearning “to think gratuitous human constructs.” We teeter back and forth, not between Jerusalem and Athens, but between Paris and Williamsburg. Markovits brings off this balancing act with skill and daring. Everyone is given their due. Instead of disrespect or easy judgment, there is generosity of spirit and delicacy of the pen.

Chasidim make their way through these pages from Transylvania, to Paris, to Williamsburg. They are matched, marry, bear children. Some leave the fold. Stereotypes are avoided: There are Simchas Torah dances, but there is also the enchantment of a Paris library, Atara’s illicit haunt, where “lamps of milk glass inside green shells cast bright ellipses of light on rustling pages.” There is joy abounding with great-grandchildren aplenty, but there is also the pain of Mila who cannot conceive. At the center of the tale is her momentous decision that upends generations. Here, it should be said, the plot takes a baroque turn. Disbelief must be actively suspended — but this is not a misstep so much as an instance of ecstatic overreaching.

This is a different set of walls and courtyards than the familiar Brooklyn-Manhattan axis. The concreteness comes from the Maramureş wood nettle, the glowering statuary and blossoming gardens of Paris, the nighttime voyages by rail. Because Markovits is French born — having published one novel in that language already — we get the Chasidic world of the United States viewed from across the Atlantic. In Paris, the Stern children are called sale juif, dirty Jew. In Brooklyn there is “kosherness splashed all over…Jews not afraid to advertise they [are] Jews, Jews reconstructing a world that never was before.”

As creator of this microcosm, Markovits’ most impressive feat of compression is to present two great moral questions in concrete Jewish terms that can resonate with any intelligent reader. The more familiar of these is the Holocaust. “Does the Lord stay to watch,” asks Atara, a skeptic even in seminary, “when children are burning?” It is a credit to the novel and its characters that even the director of the girls’ seminary of whom this question is asked does not have the chutzpah to answer it immediately.

The more difficult question involves repercussions of individual decisions, whether a community can judge violators by its own lights. In the Jewish terms of Markovits’ plot: how do you solve the problem of the mamzeres and her descendants? How can deceit be assimilated into the stories a family tells about itself? Are there boundaries that can be crossed, and then crossed back again in the other direction — keeping what was learned on the outside while finding a place at the Shabbos table? There are answers here, but the story, its characters, and the created world are primary.

This is a book absorbing as any midrash and as enlightening as a library. I feel its contribution immediately and powerfully, and am happy to have given my time to it. I recommend you do the same.