Is UK on Brink of Economic Collapse?

Alex Krainer

The sequence of events that took place during the last few months of this year, including the presidential elections in the United States and the war in Syria overshadowed important developments in the news cycle, especially on the economic front. One of them is the approaching collapse of Great Britain.

I believe that we are close to the precipice of events that will remain recorded in history, perhaps like the 1921 Weimar republic hyperinflation, 1929 stock market crash, or the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. The events will cause a lot of pain for great many people, but if we correctly anticipate them and prepare for the coming changes, at the very least we should be able to weather the storm intact.

[…]

Catastrophic fiscal conditions[…]

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) recently downgraded Britain’s economic prospects. They predicted that in 2024, the UK will have the worst performing economy among all the G7 nations with an expected growth of only 0.4%, not 1.1%; and 1% in 2025, not 2%.

But as it now turns out, even the OECD was much too optimistic. Namely, the official figures show that the British economy actually shrank 0.1% month-on-month for two months in a row, in September and October 2024

[…]

The most important indication that something was very wrong was the fact that the Bank of England (BOE) felt obliged to open the monetary spigots wide. Recall, on 22 July they hastily introduced a repo program, announced as a bold “transition towards a new system for supplying reserves” to financial institutions. This move was clear evidence that one or more of British financial institutions were about to collapse.

By September 5, the program already ballooned to over £40 billion. We’ll take a small detour to talk about repos here because it’s important to explain what repos are and why BOE’s launching a repo program is significant. If you feel you know enough about repos, feel free to skip to the next heading.

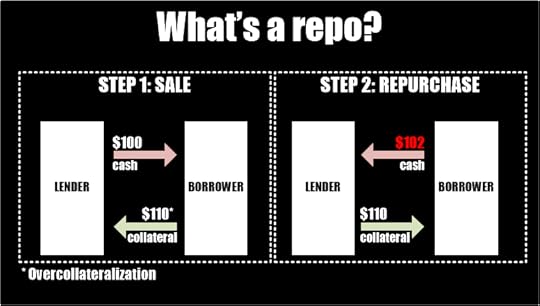

The repo red flagRepos or repurchase agreements are an important source of funding for large financial institutions. A repo is a form of borrowing where the borrower sells securities to the lender with an agreement to repurchase them at a slightly higher price. Simply, it’s a form of secured loan. In the first step of the transaction, the lender buys some financial assets from the borrower.

The assets also represent the collateral which secures the loan. Normally, the collateral in question would be highly liquid, low-risk securities like government bonds, but they could also be mortgage-backed securities. In the second step, the borrower repurchases the securities at a higher price. The difference between the sale and the repurchase price reflects the interest on the loan that’s due to the lender. The lender might also demand that the loan be overcollateralized: that the value of the collateral exceeds the purchase amount by some percentage.

Repos are usually very short-term transactions, most often overnight, but they can also be arranged for longer time intervals spanning several days or several weeks. They can also be open ended, with no term specified. As a rule, in repo transactions the lenders are private, non-depositary financial institutions or money market funds. For them, repo transactions are a lucrative source of investment returns as they earn reliable interest income in transactions that are almost risk-free. The borrowers are usually investment banks for whom the repo market is a critically important source of liquidity.

In the U.S. over a $1 trillion in repo transactions are conducted each day. During financial crises, however, the repo market is one of the first to seize up. If a borrower is unable to repurchase the securities they sold, the lender might remain stuck with the collateral. In a crisis, the value of that collateral could collapse. In such conditions, the lenders might demand higher interest rates and higher rates of recollateralization. They might even be unwilling to engage in repo transactions at all.

In 2007, the Global Financial Crisis was catalyzed by a run on the repo market: the funding for investment banks became either prohibitively expensive or entirely unavailable. At that time the Fed did not enter the repo markets, but Ben Bernanke injected at least $1.5 trillion of liquidity by purchasing financial assets through other, longer-term facilities.

In 2019, yet another financial crisis was about to hit the proverbial fan. In August 2019, the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, James Bullard said that, “Something is going on, and that’s causing, I think, a total rethink of central banking and all our cherished notions about what we think we’re doing… We just have to stop thinking that next year things are going to be normal.” Well, as we now know, within a few months we got the New Normal!

The repo rates in the U.S. have been rising steadily since 2015, but by 2019 that trend began to accelerate quite sharply. On 16 September, repo rates exploded to 8%, fully 6% above the Fed Funds rate.

To avert another, much bigger Lehman Brothers moment, the Fed hastily intervened as the lender of last resort, providing tens of billions of dollars in liquidity to the repo markets. The intervention was supposed to be only temporary. The Fed’s repo facility was meant to be shut down by 10 October 2019. Except it wasn’t: instead, it continued to expand from the initial $53 billion to surpass $200 billion by the end of October.

We don’t know the full story however, because like the British authorities today, the Fed kept things very obscure. Writing about the episode in January 2022, Fed Watchers Pam and Russ Martens wrote that, “We’ve never before seen a total news blackout of a financial news story of this magnitude in our 35 years of monitoring Wall Street and the Fed.” The Fed never had disclosed which banks got how much repo cash[1]. The reason for all the secrecy was that the problem was much bigger than we were told and it wasn’t limited to the United States.

On Saturday, 19 October 2019 the World Bank Group and the International Monetary Fund held a meeting in New York. On the occasion, UN Secretary-General António Guterres spoke and underscored that the world economy was in “tense and testing times,” and facing severe headwinds. He pleaded with the overlords of global finance to “do everything possible” to avert the “the possibility of a Great Fracture” in the world. By January 2020, we had numerous reports about interbank lending and commercial credit drying up in Europe, with banks issuing margin calls and cutting credit lines. It appeared that a massive financial crisis was imminent.

But just then, a miracle happened!But just then a fortuitous event almost miraculously rescued the banking system. The World Health Organization declared the Covid 19 pandemic, creating the perfect smokescreen for the bankers to stage a veritable global banking coup followed by the largest ever bailout of the entire Western financial system.

In the U.S. the CARES Act was passed, providing a $6.2 trillion ‘stimulus’ package for the economy. How much is $6.2 trillion? It is nearly $20,000 per man, woman and child living in the United States. Not only that, US lawmakers somehow had the foresight to introduce this Act into the Congressional procedure already in January 2019, more than a year before the pandemic was declared.

Ultimately, the total bailout gifted to the bankers exceeded 10 trillion dollars – well more than $30,000 per man, woman and child living in the United States.

That sum clearly dwarfed the Fed’s repo facility, but the repos were essential in averting the collapse in September 2019. Thanks to their opacity and complexity, repos saved the day as a sort of a Swiss Army knife in the bankers’ survival toolkit. For example, they can serve as a means of perpetual bailout: among others, Lehman Brothers systematically used repo transactions to conceal their investment losses and create for a time a false impression of liquidity. For central banks, repos can be a covert mechanism of monetary policy. The Reserve Bank of India routinely uses repos and reverse repos to increase or decrease money supply in the economy.

Today, it seems that we are at the precipice once more. Keir Starmer’s budget represents the largest fiscal loosening since the 2020 lockdowns and the Bank of England is flooding the financial system with liquidity. It is fair to ask then, how bad could things be in the UK?

The black hole: £71 or £22 billion?I don’t really know the answer to that question. As a market analyst and a former hedge fund manager, I regularly read the financial press, and I’ve done so for over 25 years. But over that time, I couldn’t help noticing that UK’s public finances aren’t subject to the same level of scrutiny as those of other nations. We hear a lot about the US, Japan, Germany, France, or China. About Britain, not so much.

What we can find from public sources isn’t exactly sensational. We already know that UK’s government debt is high and rising; in 2023 it was nearly £116 billion, 27% more than the year before. UK’s Office of National Statistics says that the government added £64.1 billion in deficit spending through August this year and that debt-to-GDP ratio reached 100%.

The figures are bad, but they’re hardly panic-inducing stuff. I suspect that the real state of things is much worse and that it is being deliberately concealed.

There are times however, when some truth breaks into the public view through political squabbles. For example, on May 1 this year, Kier Starmer confronted then Prime Minister Rishi Sunak about the £46 billion black hole before correcting himself, first to £64 billion and then to staggering £71 billion! Whatever the case, the “black hole” is there and it is probably much bigger than we know. Of course, by the time Starmer became Prime Minister, the hole had magically shrunk to ‘only’ £22 billion – the sum that’s perhaps small enough that it can be fixed in part by freezing a few thousand pensioners this winter.

The system that demands human sacrificeIncidentally: what is this financial system that requires a limitless flow of free money to gorge the gods of finance while at the same time it inflicts savage austerity on the poorest and most vulnerable members of society, condemning many of them literally to death. Whatever the Gods of finance are, they clearly demand human sacrifice. Our liberal democracies fear these gods enough that they are prepared to appease them at an industrial scale.

To save about £1.4 billion, Sir Keir Starmer has decided to cut winter fuel subsidies to 10 million pensioners in Britain. Back in 2017 Tory Prime Minister Theresa May floated a similar proposal. At the time, Labour was in opposition and their own research concluded that cutting winter fuel allowances would kill an estimated 3,850 pensioners that winter. That was five years before “typical household energy bills increased by 54% in April 2022 and 27% in October that year.

Britain now has the highest cost of energy in the world and the required human sacrifice could turn out considerably higher than 3,850 pensioners, all to save a relatively insignificant sum of money: a mere £1.4 billion of the supposed £22 billion fiscal black hole.

[…]

Then there’s the all-consuming Project Ukraine. From February 2022 until now, Britain allegedly spent more than £13 billion in aid to Ukraine. But the real damage from this misadventure cost many times more. Sanctions against Russia have caused extensive damage to Britain’s economy, starting with a sharp increase in prices of energy and other inputs. Farmers reported that the cost of fertilizer has quadrupled, from £250/ton before the sanctions to £1,000/ton today. Many British companies lost business on account of sanctions.

[…]

Via https://alexkrainer.substack.com/p/the-fall-of-britain-part-2

The Most Revolutionary Act

- Stuart Jeanne Bramhall's profile

- 11 followers