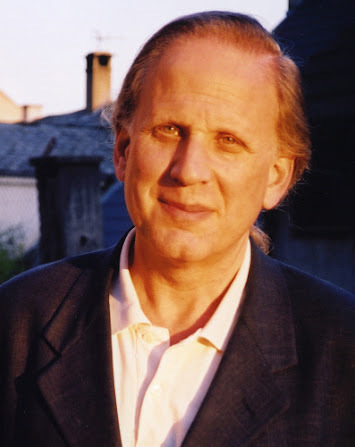

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Roger Greenwald

Roger Greenwald grew up in New York City. He attendedThe City College and the Poetry Project workshop at St. Mark’s ChurchIn-the-Bowery, then completed graduate degrees at the University of Toronto,where he founded and edited the international literary annual WRIT Magazine.He has published four books of poems: Connecting Flight(Williams-Wallace), Slow Mountain Train (Tiger Bark), The Half-Life(Tiger Bark), and in October 2024, An Opening in the Vertical World(Black Widow). He has won two CBC Literary Awards (for poetry and travelliterature), the 2018 Gwendolyn MacEwen Poetry Prize from Exile Magazine,and the 2024 Littoral Press Poetry Prize, as well as many awards for histranslations from Scandinavian languages. More, including videos from booklaunches, at www.rogergreenwald.org .

Q: How did your first book change yourlife? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent?

A: My first book didn’t change my lifeat all. It bestowed on me the label “published poet,” a phrase that peopleoutside the literary world imagine is a compliment. I think that formally myfirst book was my wildest, its music the jazziest. To whatever extent mysubsequent books are edgy, their venturesome explorations are more about statesof mind or states of being than about form. But in my most recent work(published only in journals so far) I have sometimes tried to stretch formagain, though in different ways from those in my first book.

Q: How did you come to poetry first,as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

A: As a reader I first came to poetryas a kid: Dr. Seuss and then Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous anthology, A Child’sGarden of Verses. I wrote my first two “serious” poems around age eight. Mymother’s father, who was a Linotype operator, set them and printed them ongalley sheets. Wish I could find those!

Q: How long does it take to start anyparticular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is ita slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, ordoes your work come out of copious notes?

A: In poetry I don’t have writingprojects (aside from translations). In prose fiction or memoir, sometimes. At aconference once, a Norwegian poet, adopting a false-naive tone, said to me, “What’sa ‘literary project’? I thought writerswrote books.” I replied, “A literary project is something that can bedescribed on a grant application.” But hats off to poets who conceive of andwrite through-composed books of high quality, crowns of sonnets, long poeticsequences, etc. The time that poems take to germinate varies, but once I’mready to write a poem, that usually goes fast. Sometimes my first draft isclose to the final version; at other times, especially with longer poems, Irevise quite a bit, in stages, and in response to feedback.

Q: Where does a poem usually begin foryou? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a largerproject, or are you working on a “book” from the very beginning?

A: A poem usually begins with a linethat I know is a good line of verse. Often it’s the first line of a potentialpoem, but sometimes it’s the last line. I make book mss from pieces I havewritten. They may be short or long, and there may be a sequence of severalpoems. But I don’t start out working on a book.

Q: Are public readings part of orcounter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doingreadings?

A: I love reading to an audience andam never nervous. I like seeing how different poems go over and hearing anycomments that people may offer. Although my readings aren’t part of my writingprocess, they do involve creative work, because I usually work with a musician,and that collaboration affects my choice of poems and increases attention totone, mood, and pacing.

Q: Do you have any theoreticalconcerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answerwith your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

A: I have a few principles (whichtheorists may choose to regard as theoretical, but which I regard aspractical). One is that in verse, every line should work as a line. That isdifferent from saying that line breaks should do something. The craft ofthe break is easier to master than the art of the line, which is a rhythmicunit held at least somewhat taut by a certain tension, and at the same time asemantic and syntactical unit that strives to offer some interest by virtue ofhow it begins and ends and what relations its words have to one another. Thoserelations may depend on logical meaning, image, and sound.

I am not trying to answer-pre-existing questions. Each poem may grow outof its own question and may then raise other questions. There are always thequestions of how to make the poem speak to others and how to shape it so itoffers aesthetic rewards, but these are not questions that can be described assubject matter.

The current questions are “What day is it?”; “Who will publish my nextbook?”; and “How can it get a competent review?”

Q: What do you see the current role ofthe writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you thinkthe role of the writer should be?

A: The writer’s role qua writeris to write well. The writer’s role as “author” is to try to give the gift ofhis/her work to readers. Writers who choose to be active in the larger cultureor polity do so as citizens and as humans.

Q: Do you find the process of workingwith an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

A: “Everyone needs an editor.” But by “editor”I mean any perceptive reader who can offer constructive criticism. For poetsthat is most often a poet colleague. But if someone at a publishing house hasqueries and suggestions to offer, that is all to the good, because all feedbackis potentially helpful. If I reject 90% of a colleague’s suggestions, I saythanks for the 10% that yielded improvements.

Q: What is the best piece of adviceyou’ve heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

A: The best advice about poetry that Iever got came from the American poet Francine Sterle: Keep assembling yourpoems into book manuscripts. Don’t wait for one book to be published or evenaccepted to start making the next one.

Q: How easy has it been for you tomove between genres (poetry to translation to critical prose)? What do you seeas the appeal?

A: It has been relatively easy for meto move between poetry and prose (whether prose poetry or fiction), and fromwriting to translating and back. But I found that writing a lot ofdiscursive prose (e.g. a dissertation) put my language-generating brain in agroove that felt more like a rut when I tried to climb out of it. As for theappeal, translation kept my hand in when for one reason or another I wasn’twriting. And the contact with another language, as well as the deep immersionin another writer’s worldview and voice that translation requires, canstimulate and broaden one’s own work.

Q: What kind of writing routine do youtend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

A: I don’t have a writing routine. Atypical day begins with reading and answering e-mail.

Q: When your writing gets stalled,where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

A: I don’t consider not-writing to bea stall. A poet can’t be writing poetry all the time. (Pity the poor novelist,Who wishes she could’ve left home, Who uses all her hours to write pages, Butstill feels like she’s pushing a stone.) At one point in my life when I simplycould not write, I did a lot of translating. But since 2016 or so I have moreor less withdrawn from translation to focus on my own work and on getting itpublished.

Q: What fragrance reminds you of home?

A: Or “Which home reminds me of afragrance?” The Bronx: furniture polish and perfume. Bergen: juniper and oldleather. Toronto: the absence of salt in the air, the smell of what’s missing.

Q: David W. McFadden once said thatbooks come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work,whether nature, music, science or visual art?

A: Music is perhaps the largestinfluence on my poetry: on the shape and movement and sound of the poems, thefeeling carried by the voice. Music is also part of the subject matter of agood many of my poems. But I have also written poems inspired by and/or aboutfilm, dance, nature, and visual art. My scientific background supplies some ofmy imagery and vocabulary, but science is not a dominant element.

Q: What other writers or writings areimportant for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

A: This could be a long list!Catullus, Whitman, Shakespeare, Donne, Hopkins, Yeats, Wallace Stevens, Dylan Thomas, Stanley Kunitz, Muriel Rukeyser, Joel Oppenheimer, John Ashbery, Joel Sloman, Robert David Cohen, Gunnar Harding, Henrik Nordbrandt, Gjertrud Schnackenberg, James Salter, Susanne Langer.

Q: What would you like to do that youhaven’t yet done?

A: Travel back in time and make betterdecisions. But “yet” implies possibilities and the future. Organize myarchives. Get my manuscripts published. Get sensitive reviews in print andreach a wider audience. Ah, the impossible creeps back into the list.

Q: If you could pick any otheroccupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think youwould have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

A: If I had had musical training froman early age I probably would have become a composer. If my early life had beenso different that I had not become writer, I might have become a medicalresearcher or, more likely, a lawyer.

Q: What made you write, as opposed todoing something else?

A: Magical thinking. The need toimagine that I could communicate with the dead and that the right incantationcould have an effect on others.

Q: What was the last great book youread? What was the last great film?

A: Poetry: Heavenly Questions, byGjertrud Schnackenberg. Novel: The Werewolf (a purely metaphoricaltitle), by Aksel Sandemose, which I was re-reading. Film: La Grande bellezza (The Great Beauty).

Q: What are you currently working on?

A: Putting together the manuscript ofanother book of poems. Submitting to journals and festivals. Trying to get myjust-published book reviewed.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;