William J. Duley: Executioner, Survivor, and Controversial Legacy

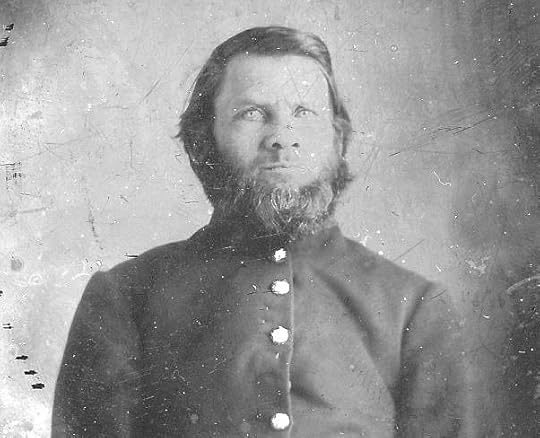

A formal glass-plate portrait of William Duley in his military jacket, probably taken between September 1862 and February 1865.

A formal glass-plate portrait of William Duley in his military jacket, probably taken between September 1862 and February 1865.

On December 26, 1862, Captain William J. Duley swung the ax that cut the rope of the gallows, simultaneously ending the lives of 38 Dakota men for their roles in the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. Duley, who at the time believed his entire family had been killed by the Dakota, joined the team of men who erected those gallows and was assigned as the executioner. In a letter to a newspaper editor written July 27, 1885, Duley stated that he supervised the gallows and that he was “known to be the person who cut the rope and launched the 38 demons into eternity.”

William J. Duley was born in Ripley County, Indiana, on March 30, 1819. He married his wife, Laura Terry, in 1848, and the two of them moved to Winona County, Minnesota, in 1856 shortly after their two children drowned in the Mississippi River. Duley had a farm and sawmill and in 1857 became a Republican delegate at the State Constitutional Convention in 1857. Four years later, he and his family moved to Lake Shetek, a remote settlement in far southwest Minnesota.

On August 20, 1862, two days after a faction of the Dakota people launched a violent attack on the settlers and agents living at the Lower Sioux Agency, the residents of the Lake Shetek settlement were violently attacked by 25-30 Sisseton warriors and women led by Chief Lean Bear of the Sleepy-Eye band set out on killing and capturing as many whites as possible. During the attack, which lasted several hours, the settlers took cover in a slough, where many of them were either killed or captured. As a result of the attack, 15 settlers were killed, while 3 women and 8 children were taken captive. Twenty-one settlers escaped to safety in the prairie. William J. Duley was among them.

Although Duley escaped with his life, he was shot twice in the left arm, an injury he said had at times left his arm paralyzed and useless. Additionally, three of Duley’s children—Willie (10), Belle (4), and Franklin (6 months)—were killed, and his wife Laura was taken captive along with his son Jefferson and his daughter Emma.

It has been reported that Duley acted bravely during the attack, defending himself and his neighbors, killing the chief, Lean Bear, in the combat. However, according to historian Harper M. Workman, “Everett, Hatch, and Mrs. Cook say Duley was a coward, that he was running when they entered the slough, and never stopped.” On the other hand, Duley’s son, Jefferson, later defended his father, saying “he fought until there was no use in continuing.”

In either case, Duley volunteered to join the army shortly after escaping the attack with his life. After the hanging, Duley joined to punitive expedition led by General Henry H. Sibley against the Dakota in 1863 and 1864. Duley learned that his wife and two of his children survived the attack on December 30, 1862, when he received a letter from Laura. The Lake Shetek captives had been freed the previous month by the Dakota Fools Soldiers, but not before many of them endured deplorable conditions, including rape. In the 1870s, Duley, Laura, and his two remaining children moved to Alabama where William worked as a millwright. According to reports, Laura was quite unwell in the aftermath of her captivity and was said to have never smiled again.

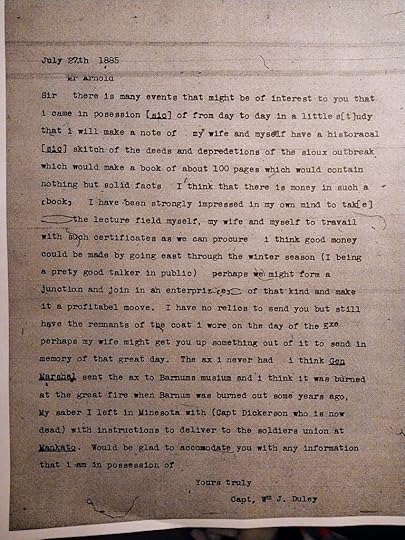

A letter written by William J. Duley to a Mr. Arnold on July 27, 1885.

A letter written by William J. Duley to a Mr. Arnold on July 27, 1885.

William J. Duley and his family suffered greatly at the hands of the Dakota during the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. He did not seem to have any regrets for his role in the largest mass execution in United States history. Toward the end of his life he pleaded for and received a pension for his volunteer service during and after the war. The ax he swung that heinous day was sent to the Barnum’s American Museum in New York where it was lost to a fire in 1865. In 1885, Duley sought to cement his legacy with a book, telling a newspaper editor “my wife and myself have a historical skitch of the deeds and depredations of the sioux outbreak which would make a book of about 100 pages which would contain nothing but solid facts.” Duley died at age 79 on March 5, 1898, and is buried at Artondale Cemetery, in Gig Harbor, Pierce County, Washington, USA. What, if anything, is William J. Duley’s legacy?

Sources:

House documents. “Report by The Committee on Invalid Pensions – July 30, 1888,” N.p.: n.p., 1888. – https://www.google.com/books/edition/House_documents/Bjcya_-fWpAC?hl=en&gbpv=0

Minneapolis Star Tribune, “Image Surfaces from a Grim Chapter,” by Curt Brown, November 1, 2015, https://www.lrl.mn.gov/LegDB/articles/12622StarTribunearticle.pdf

Duley, William J. Notes on Sioux Massacre of 1862, 1885. N.p., 1885. Print.

Colin Mustful is a celebrated author and historian whose novel “Reclaiming Mni Sota” recently won the Midwest Book Award for Literary/Contemporary/Historical Fiction. With a Master of Arts in history and a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing, Mustful has penned five historical novels that delve into the complex eras of settler-colonialism and Native American displacement. He is also the founder and editor of History Through Fiction, an independent press dedicated to publishing historical narratives rooted in factual events and characters. Committed to bringing significant historical tales to light, Mustful collaborates with authors as a traditional and hybrid publisher. Residing in Minneapolis, Minnesota, he enjoys running, playing soccer, and believes deeply in the power of understanding history to shape a just and sustainable future.