My Personal Archive System

Photo by Element5 Digital on Pexels.com

" data-medium-file="https://i0.wp.com/jamierubin.net/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://i0.wp.com/jamierubin.net/wp-c..." src="https://i0.wp.com/jamierubin.net/wp-c..." alt="gray steel file cabinet" class="wp-image-25694" srcset="https://i0.wp.com/jamierubin.net/wp-c... 1880w, https://i0.wp.com/jamierubin.net/wp-c... 400w, https://i0.wp.com/jamierubin.net/wp-c... 550w, https://i0.wp.com/jamierubin.net/wp-c... 768w, https://i0.wp.com/jamierubin.net/wp-c... 1536w, https://i0.wp.com/jamierubin.net/wp-c... 1200w, https://i0.wp.com/jamierubin.net/wp-c... 1800w" sizes="(max-width: 900px) 100vw, 900px" />Photo by Element5 Digital on Pexels.comFor years, I’ve wanted a personal archive system that allows me to easily search all of my documents, email, and other information in a useful way. Over the last few months, I’ve finally built the first iteration of what I am calling my Personal Archive System, or PAS for short.

Back in September, I wrote about how I archived all of my blog posts in Obsidian. That was an experiment to test the viability of such an archive. It provided me with plenty of files (more than 7,000) to test out different search engines. The files are all text files, which makes things like full-text search much easier. Being text files was important because, around that time, I began doing all of my work in plain text (not even Markdown) with few exceptions. Working in plain text makes the archiving process that much easier.

Why a Personal Archive?I began using a computer when I was around 11 years old, and I’ve been using them for practical things like writing papers and sending email since 1990. The vast majority of my output and my communications are in digital format. It would be wonderful to access all of that from a simple interface. Moreover, I had some other important requirements:

I wanted a one-stop shop to search everything.I wanted the system to be entirely offline. I didn’t want to have to rely on the Internet to search my archive. I wanted it all local.I wanted it to be easy for my family to use.I didn’t want to depend on commercial or other tools that seems to come and go with increasing frequency these days.While there are tool and systems and combinations thereof that might be able to do this, none of them do it the way I want it done. I want a clean simple interface that makes everything easy. So with these requirements in hand I set out writing the system, mostly in Python, using Flask as my front end framework and Whoosh as my search engine on the back end. I use SQLite databases for important indexes and other data storage. I finished the initial functionality a few weeks ago and have been using my system daily to ensure it works well for me. So far, so good.

Core Features of the SystemCurrently, there are four core features of the system:

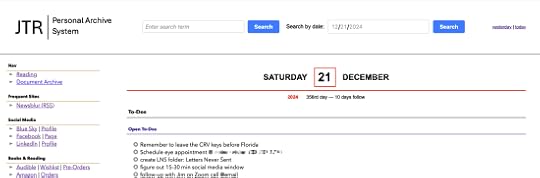

Searching the archive. This includes searching everything in the archive, whether it is blog posts, notes, email, or information about books and reading in my book database.Viewing almanac data for any given date. In the initial release, almanac data includes:Agenda (calendar items) for the dayWhat I was reading (or started or finished reading) on a given dayWork products I created or worked on during the dayEmail I sent or received on that dayBrowser history of all of the sites I visited on the dayCommand line history for any command I issued during the dayTo-dos. The system manages my to-dos based on a simple text file I track them in.Managing my books and reading. This in itself is an entire subsystem that tracks the books in my collection as well as my reading of those books, articles, stories, and notes related to them.Here, for instance, is the home page of my personal archive system:

Personal Archive System home page

The home page simply lists the agenda for the day as well as open to-dos. But I can use the PAS to see an “almanac” for any day. For instance, here is the almanac for yesterday::

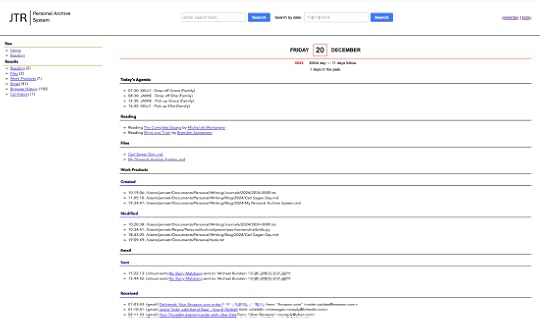

Almanac page from PAS

The left nav summarizes the almanac: I was reading two books (same ones as today). Two files were added to the archive. I worked on seven files throughout the day, creating three and modifying four. I sent two emails and received 41 emails, and I browsed 182 sites and ran one command at the command line. If I scroll through the list I can see the times at which I did these things, or drill into the details of any one of them without ever having to be online.

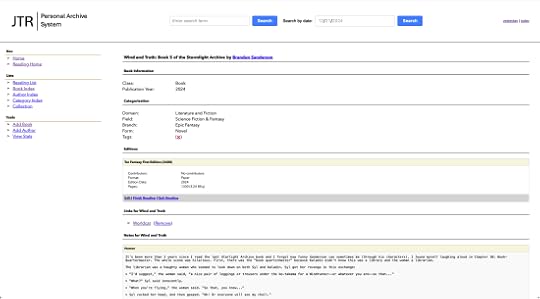

Here is a snippet further down the almanac for yesterday that shows some of the sites I visited and commands (or in this case, command) I issued.

Some of the browser history and command line history.

Since the site runs on my home network, it is accessible to the family as well, and they can use this for searching or to find out when something happened. It might seem silly to have so much detail, but I can’t tell you how many times I have visited a site and then forgotten what the site was and spent a long time trying to figure it out. Or, run a series of commands to install some software and then needed to recreate that again on another system.

The Reading SubsystemHere is the homepage to the book/reading subsystem:

PAS Reading Home

My reading list knows my reading goals for the year and shows me my progress toward the goal. With just 10 days left in the year, I’m not going to make my goal, alas. The reading home page lists the books that I am currently reading and provides one-click actions to “finish” or “quit” the book. Note that it also provides an estimated completion date for each book. These estimates are based on nearly 30 years of reading list data and reading behavior and it turns out these estimates are is pretty accurate in the field.

Note that the dates in the list are hyperlinked? Clicking on a date takes me to the almanac entry for that date. Convenient!

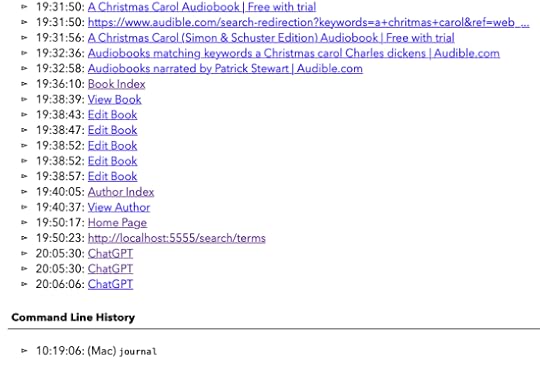

There is a lot that I can do with this. For instance, I can click on a book to see its details. Here are the details for Wind and Truth by Brandon Sanderson:

PAS Record for a Book

It has basic information about the book and then lists editions of the book that I have. When I read a book, the edition that I am reading gets added to the reading list, and that is why the edition here shows a “Finished Reading” and “Quit Reading” link — it knows I am currently reading this edition.

Below, you can see part of a note I’ve added for the book. I can add any number of notes. And the nice thing is that all of this is searchable as part of a global search of my archive.

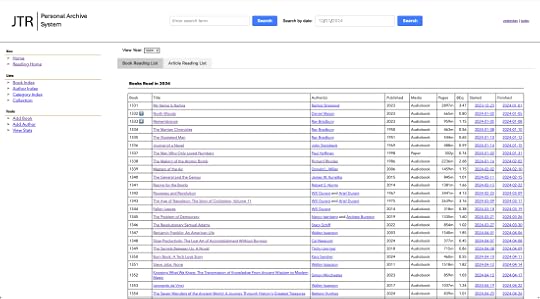

I can also look at my complete reading list. By default, I see the current year:

Reading list for 2024

On some of the books in the list, you’ll see a blue number like the “7” for North Woods or the “4” for Remembrance. These books are ones that I have ranked as part of my best reads of the year (the rankings may change before the end of the year).

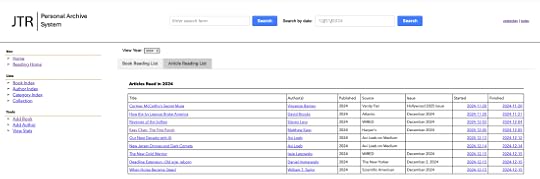

In addition, as part of this system, I’ve started tracking the articles and other short works that I read. There is a separate tab for those. Clicking on that tab, I see:

Articles I’ve read

Just like with books, I can add notes and links to the articles, too. I can easily search through all of my books to find something specific, like this:

Searching titles

And I can do the same for authors. And I can add new books or articles, edit existing books, etc. There’s more that my book system can do, but you get the idea.

How the PAS System WorksFor those curious about how the system works, there are four key components:

Archivers. These are scripts that archive a particular type of information. Currently, I have two archivers: one for text files and one for email. The text file archiver searches a set of folders on my file system for different types of text files (.txt, .md, etc.) and copies them into an archive folder. It registers the file in a SQLite database. I use a hash of the file to see if the file has changed or the path has changed. When a file changes, the archiver updates the archive with the latest version of the file. The email archiver works by logging into my email accounts and checking for any new mail that it doesn’t already know about. It downloads the message, stores the message as a text file in the archive, registers the message in a SQLite database, and also stores any attachments associated with the message.Indexers. There is one indexer for each type of data. The indexers go through the data in the archive and index it using Whoosh so that it is full-text searchable.Almanac Agents. There is an agent for each kind of data I collect in the almanac. So there is an agent for pulling calendar information, gathering information about work products, pulling browser and command line histories, etc. Data from these agents is stored in SQLite databases.API. There is an underlying API (via Flask) that allows me to access the data through the front end.Each morning at about 4 a.m., the archivers run, gathering any new files or email. Once the archivers have completed their task, the indexers run to add the new data to the search indexes. Almanac agents typically run hourly, although the work product agent runs every 15 minutes.

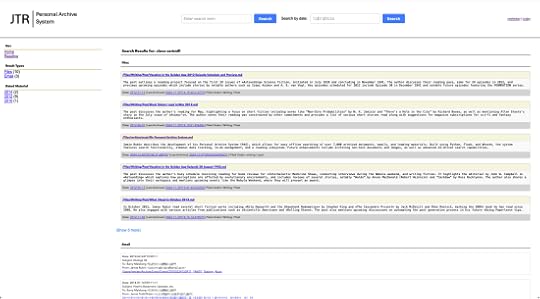

Together, these allow me to search everything in my archive. In one of my first really helpful tests, I wanted to know if I’d ever written anything about Cleve Cartmill. So, I went to my archive and searched for “Cleve Cartmill.” The result quickly came back with nine files and three email messages. The results are returned as follows, and the sidebar lets me filter by date:

Search results

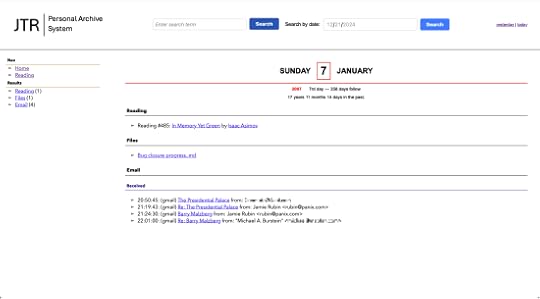

Since then, I’ve used the system for all kinds of searches. Indeed, according to the data the system collects, I’ve run 685 searches (some of them, of course, were tests). In addition, the almanac lets me go back in time. For instance, here is the almanac for January 7, 2007:

The almanac shows me how long ago the entry was–in this case 17 years, 11 months, and 14 days in the past. On that day, I was reading Isaac Asimov’s In Memory Yet Green. I published a blog post called “Bug Closure Progress” and I received 4 pieces of email.

Currently, my PAS contains:

99,836 email messages going back to 2004 (that’s 20 years worth of email)6,676 attachments associated with the email7,027 text and markdown files46,674 browser history events4,766 calendar events6,338 command line events11,209 work product events (for 10,323 work products)1,219 books and articles574 authorsCurrent DevelopmentWith an initial version working well, I’ve started on three new features: archiving “documents” and archiving curated images. Documents are things that aren’t text files, like Word or Excel files. There is a more involved process for archiving these, but it allows me to set up what I call “contexts,” which makes searching for things much easier.

I’m also working on archiving curated images. For these, I’ve experimented by sending the image to an LLM and asking for a description of everything it sees in the image, along with some search terms that someone might use to locate the image. I store this text in a SQLite database and relate it to the image in question so that when I run a search of the archive, that text is searchable and the image is returned in the search results.

But the thing I have been focusing most on is my journals. A few months ago, I ran an experiment that demonstrated that an LLM could read and transcribe both my print and cursive handwriting with a very high degree of accuracy. I’ve got a sample of 160 pages of journal entries that are now searchable as part of the archive. Moreover, they don’t just return the text but also the image of the page the text appears on.

Future DevelopmentThere are three big features I’m looking at adding in the future, once I have accumulated enough data in the archive. The first is to create embeddings for all of the files and emails using AI and storing the embeddings in a vector database to allow me to run cosine distance searches against the data. That should greatly improve the search results and take a step toward more natural language searches.

The second is to make use of semantic searches to allow for more natural language searching while returning relevant results.

Both of these are months in the future at this point. For now, I’m just happy to have a working system that I use more and more each day.

Finally, I am working on a way to associate artifacts (files, documents, email, photos) with people so that I can, for instance, select my older daughter’s name from a list and see everything I have in my archive related to her, and then filter down from there.

This is what has been keeping me so busy, but now that the core components are up and running, I am once again free to do a little more writing here on the blog. I thought you might want to know what I’ve been doing in the meantime.

Questions?I suspect this post might generate a number of questions. I’ve tried to anticipate some of them here, but if you have others, feel free to drop them in the comments and I’ll do my best to answer them:

Are you still using Obsidian?Not really. As I mentioned, I’ve switched mostly to plain text files. I used Sublime Text as my main editor for these, but the nice thing about plain text is that I can use almost any editor to edit the files. The archive itself has take the place of Obsidian. I think Obsidian is a fantastic tool, but to keep things simple, I use plain text and the archive system to manage all of my data. I do still use Obsidian as a public repository of my reading list.

Will you open source the code?I’ve made of lot of my code available in the past. While the code is in GitHub, it is currently housed in a set of private repos. While to system works well, the code behind the scenes is pretty messy. It also highly tailored to my needs. My experience with a big system like this is that if I made the code publicly available, even with the caveat that there is absolutely no support whatsoever, I’d still get a lot of email asking for help, especially getting it up and running the first time. I just don’t have the time to commit to that right now. Maybe in a later iteration, but not now. Sorry!

What about security?This runs entirely locally on my home network, which is encrypted. The archive is stored locally, backed up locally, and also backed up as encrypted backup to my cloud backup service. I feel pretty good about the level of security and don’t lose any sleep over it.

How scalable is the system?Good question. That remains to be seen. Whoosh is an older search technology, but far simpler to use than something like Lucene. I went down the Lucene path for a while and while it is more powerful and scalable than Whoosh, it didn’t seem worth the effort for a hobby project like this. So far, the searches run quickly for the most part. I don’t anticipate a huge growth on this, maybe one order of magnitude and I can revisit performance then if it warrants it.

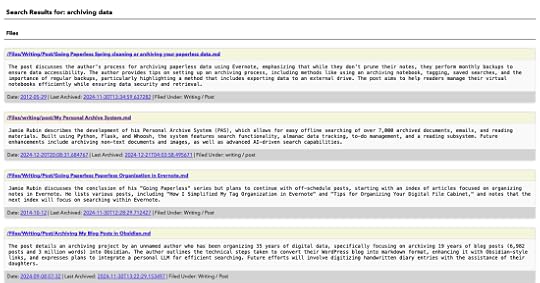

You mentioned using AI in future features. Is the system using any AI now?There is one place where the system uses AI today. When I pull in a new text file, I use an LLM to summarize the text and the summarized text is what is presented in the search results, as opposed to the first n characters of the file. I find this to be more useful than the first few lines of a file. I use a local model via LM Studio and Llama 3.2 3B Instruct to generate the summaries, with an option to use Open AI. You can see these summaries in search results like this for the search “archiving data”:

The summaries you see in the search results are generated by an LLM.

If you have other questions, drop them in the comments.

Did you enjoy this post?

If so, consider subscribing to the blog using the form below or clicking on the button below to follow the blog. And consider telling a friend about it. Already a reader or subscriber to the blog? Thanks for reading!