Heart, Mind, and Spock

I have a poster that reads, “Everything I need to know I learned from Star Trek.” I am basically in sympathy with that, though I would cast my canon wider. Fantasy, horror fiction, science fiction, and superhero comics are certainly my religion. Nothing strikes deeper in me. Nothing so fires my imagination. And if that were all it did, it would be more than enough. But there is also the great amount of wisdom I have found there. Carol and I were just the other evening discussing Mr. Spock as he appears in Star Trek: The Motion Picture, you know, the first of the movies, and the one in which earth is in danger from the interloping space entity “V—ger.”

The plot combines two venerable TV episodes, the one where Kirk and Spock defeat the huge doomsday weapon called the Planet Killer and the one in which they bring aboard Nomad, a robot operating under instructions to sterilize organic life wherever it is found. V—ger turns out to be one of the old Voyager probes launched by NASA. As its spent hulk drifted through the galaxy the probe was snatched by the inhabitants of a world of living machines who recognized it as a kindred “life”-form and repaired it, greatly enhancing its powers and imparting artificial intelligence to it. Then they sent it on its way to find and unite with “the Creator.” It knows it is missing something, and it believes that when it locates its Creator, it will find fulfillment. At length the Enterprise crew realize they, humanity, constitute the Creator V—ger seeks. V—ger has already killed a crew member and reconstituted her as an android with her personal memories buried deeply in her programming. Her one-time lover is young Commander Decker (son the Commodore Decker, a tip of the hat to the Planet Killer episode, where Commodore Decker died in an attempt to destroy the Planet Killer, V—ger’s prototype). He and she join in some kind of cosmic embrace on the surface of V—ger and are absorbed into the entity, presumably living happily ever after.

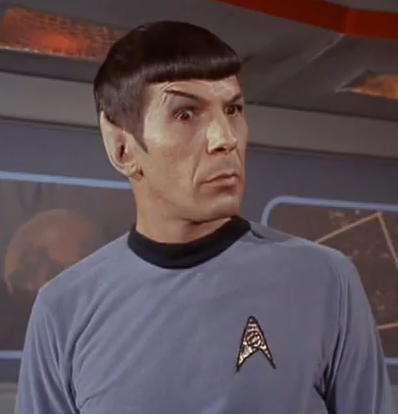

But the real star of the trek is Spock. He had not rejoined the rest of the Enterprise crew at the start of their adventure because he was away on Vulcan, undergoing the ancient ritual whereby one exorcised all emotion and embraced pure and total logic. It had been the means whereby the ancient Vulcans had saved their civilization from self-destructive barbarism, repressing all emotion. Spock, as you know, is an Earth-Vulcan hybrid and had always struggled with the emotional nature inherited from his human mother. But here, on the very verge of attaining his apotheosis into complete cerebral perfection, he stops short and quits the process. He hears the call of V—ger from across the leagues of space and boards a Federation shuttlecraft to catch up with the Enterprise, headed for an encounter with V—ger.

We see how close he came to logical Stoicism when he is welcomed aboard with great affection by all the bridge crew. But to their tearful, joyous greetings he turns a deaf pointed ear. Never on the original series was he shown quite so dispassionate, so unmoved. Everyone is puzzled. Eventually he makes an unauthorized trip outside the ship in a one-man craft, into the very depths of the huge mecha-mind of V—ger. It seems he had shared V—ger’s quest. Both had discovered, upon attaining total logic, that logic was not enough. Upon Spock’s return, Kirk asks him what was this missing piece, for which V—ger searches, and which Spock now appears to have found. Spock clasps his old friend’s hand and says, “This! Simple feeling!” And, as I anticipated, V—ger finds it, too, by the end of the film. Spock and V—ger reflect one another. Spock is never again, in any of the movies to follow, bereft of emotion or pretending to be. He exudes compassion and wisdom, though he thinks no less logically than before.

Obviously, Spock is also a depiction of every human being. For we are all possessed of both reason and feeling, heart and mind. In Spock this is symbolized by his mixed parentage, but it is an allegory for all of us. Plato told how we require balance among the elements of human existence, just as society as a whole requires justice between the classes within it. Reason must rule, while not suppressing, the courage/spirit/will and the appetites. It is not that all our aspects or instincts deserve an equal voice. Reason must be in charge ultimately, but that means only that our other traits and tendencies must be exercised in a rational manner.

The same challenge (or a very similar one?) is described when we distinguish the role and function of the left brain hemisphere (rational, analytical, scientific, mathmatical) and the right one (affective, emotional, creative, artistic). In mad scientists and nerds there appears to be an imbalance between the hemispheres, so that someone especially well-endowed with regard to the left brain gets short-changed in the right. Dr. Frankenstein (at least in the Hammer Films) is all scientific curiosity with an inadequate moral sense. He cannot empathize with his (usually unwitting) experimental subjects as fellow humans. For him, morality is one more abstraction, but one he cannot seem to take much interest in. He has a deficit when it comes to the right brain, and to the heart.

The opposite danger might be the “bleeding heart liberal” who is proverbially willing to sacrifice the rights and safety of innocent victims (and potential victims) because of misplaced empathy for the murderer. More compassion for the criminal than for his prey. His is the hyper-conscience that jumps out of the lifeboat to give place to the ruffian who is glad enough to take his place and will never consider making such a sacrifice for anyone else. The result of the bleeding-heart sacrifice is to remove the last ounce of compassion from the boat, and this in the very name of compassion. Parents have too much mind, not enough heart, when they raise their kids as if they were soldiers in boot camp. They have too little mind, too much heart, when they decide to treat their children as their friends, eschewing any attempt to govern or discipline them out of a misplaced sense of “children’s rights.” Of course, as human beings, they have rights, but not yet equal. Parents perforce possess superior rights till their kids are adults (even young adults), and these are exactly commensurate with the added responsibility they bear during the same period. “Ya gotta have heart,” but ya also gotta have mind.

Star Trek depicted this, too, in the episode where Kirk was split into his Jeckyll and Hyde halves through a transporter accident. His “good” side was rational but impotent, hag-ridden by doubts, and indecisive. No one was safe with him as leader. (Or with Jimmy Carter.) But his opposite number was a malevolent savage, too stupid and mercurial to provide peace and security for those he led. How strange that there should thus be moral-intellectual syndromes, surprising alliances of psychological elements as well as oppositions between those alliances! Spock learned that the integrated person must govern the mind with the heart and the heart with the mind. We need to learn that, too. Kirk learned that he had to supplement appetite with temperance, strength with wisdom, confidence with empathy, compassion with backbone. Who doesn’t need to learn that? Granted, you don’t have to learn it from Star Trek in particular, but I can think of much less desirable classrooms. Ultimately the optimum classroom for this education is the long-term school of your own life.

Robert M. Price's Blog

- Robert M. Price's profile

- 237 followers