Week 3, Day 1: Self as Body

“I wouldn’t be caught dead without a body.” – W.H. Auden

“I praise you because I am fearfully and wonderfully made…” – Psalm 139:14

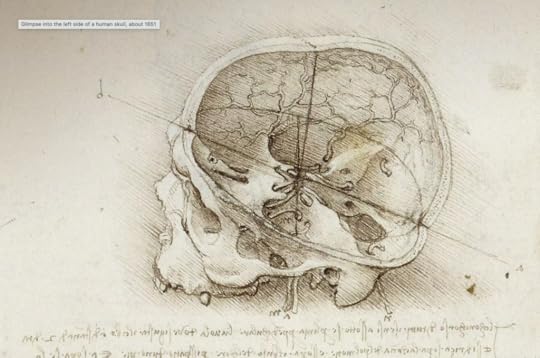

Leonardo DaVinci’s anatomical drawing of a skull, from the Max Planck Institute

Leonardo DaVinci’s anatomical drawing of a skull, from the Max Planck InstituteIn week one I talked about perceptions and how they impact our consciousness. In week two I talked about our automatic responses. This week I’m going to address another aspect of consciousness: our self-awareness.

In our earliest experience of consciousness, there is hardly any “self” to speak of. Freud called it the “oceanic feeling,” the sense that you are connected to everything, like an unborn baby in the womb. Even after birth an infant, he said, has little sense that she is distinct from her mother. There’s simply a need, like hunger; a cry for attention; and a response, like a breast. Freud theorized that this “oceanic feeling” of connectedness, this inability to distinguish self and other, is at the heart of religious mystical experience, and reflected a desire to return to this naïve, connected state. (Freud was not a fan of religion).

I’m not sure Freud was correct about all that. Research on the neural development of infants shows us that their mirror neurons start working only a few days after birth. Mirror neurons allow them to imitate facial expressions and respond to the emotions of people around them. They begin developing self-other maps with a week or two. While they may have a sense of connectedness, they start to form impressions about the character of other actors in their environment before they even have words.

Researcher Paul Bloom theorizes that babies have a sense of fairness and morality even before they’ve been taught about these things. When babies watched a cartoon of abstract shapes helping or hindering each other, they showed a preference for the helpful shapes over the unhelpful ones. Fairly early in our lives we develop a theory of mind and the foundation for what will become our ethics.

I appreciate David Benner’s understanding of our developing identity in his book Spirituality and the Awakening Self. He suggests that as infant humans gain control of their bodies, they come to understand the self as a body. “I’m in here,” inside my skin, and “the universe is out there.” We develop the idea that this self is perceiving the world from behind our eyes.

As we go through life, Benner continues, our sense of self enlarges: I am a body, but not just a body; I’m also part of a group. But I’m not just a member of a group; I am also my memories and emotions; I am my role (a parent, a sibling); I am my beliefs (a Christian, a Jew, an atheist); I am my job. A healthy sense of self incorporates these things, but also realizes that I am more than all of them, and I’m more than the story I tell myself about myself.

A sense of self, a location for our consciousness, forms the foundation for everything else. We are each incarnated or enfleshed in such a way that it is difficult to imagine having a consciousness without a body. Our most primal senses of bodily touch and smell communicate to the infant brain, “you are safe.” This closeness is so important for human thriving that babies who do not get cuddled may simply die.

In the Christmas story, God enters human life as an infant—disoriented, bewildered, and with little sense of self. As the infant Jesus grows, he changes. In the incarnation, God demonstrates to humanity that the spiritual is also physical, and that love is meaningless without touch and care for physical pain and pleasure. God, the Great “I AM,” has a body.

Prayer: Divine Mother and Father, we give you thanks for these fragile, incredible, glorious, malfunctioning bodies. May we take the care of all of them, ours and others’, seriously. Amen.