December 13, 1942 – World War II: Second day of Operation Winter Storm, the German attempt to relieve the trapped forces at Stalingrad

In early December 1942, General Erich von Manstein,commander of the newly formed German Army Group Don, which was tasked withsecuring the gap between German Army Groups A and B, was ready to launch arelief operation to Stalingrad. Began on December 12 under Operation WinterStorm, German Army Group Don succeeded in punching a hold in the Soviet ringand advanced rapidly, pushing aside surprised Red Army units, and came towithin 30 miles of Stalingrad on December 19. Through an officer that was sent to Stalingrad,General Manstein asked General Paulus to make a break out towards Army GroupDon; he also sent communication to Hitler to allow the trapped forces to breakout. Hitler and General Paulus bothrefused. General Paulus cited the lackof trucks and fuel and the poor state of his troops to attempt a break out, andthat his continued hold on Stalingrad would tie down large numbers of Sovietforces which would allow German Army Group A to retreat from the Caucasus.

On December 23, 1942, Manstein canceled the relief operationand withdrew his forces behind German lines, forced to do so by the threat ofbeing encircled by Soviet forces that meanwhile had launched Operation LittleSaturn. Operation Little Saturn was amodification of the more ambitious Operation Saturn, which aimed to trap GermanArmy Group A in the Caucasus, but was rapidly readjusted to counter GeneralManstein’s surprise offensive to Stalingrad. But Operation Little Saturn, the Sovietencirclement of Stalingrad, and the trapped Axis forces so unnerved Hitler thaton his orders, German Army Group A hastily withdrew from the Caucasusin late December 1942. German 17th Armywould continue to hold onto the Taman Peninsula in the Black Sea coast, and planned to usethis as a jump-off point for a possible future second attempt to invade the Caucasus.

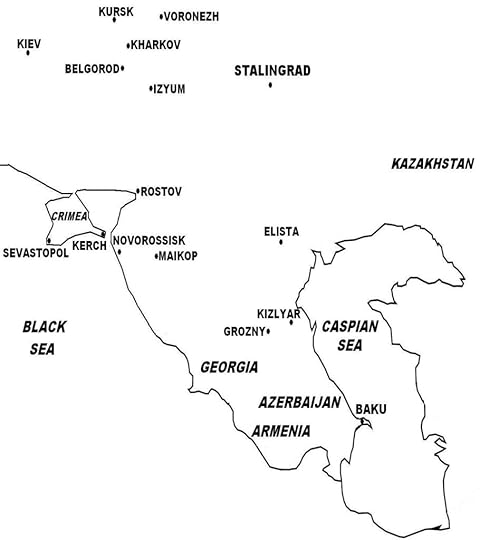

Case Blue.

Case Blue.(Taken from Battle of Stalingrad – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Meanwhile to the north, German Army Group B, tasked withcapturing Stalingrad and securing the Volga, began its advance to the Don River on July 23, 1942. The German advance was stalled by fierceresistance, as the delays of the previous weeks had allowed the Soviets tofortify their defenses. By then, theGerman intent was clear to Stalin and the Soviet High Command, which thenreorganized Red Army forces in the Stalingradsector and rushed reinforcements to the defense of the Don. Not only was German Army Group B delayed bythe Soviets that had began to launch counter-attacks in the Axis’ northernflank (which were held by Italian and Hungarian armies), but also byover-extended supply lines and poor road conditions.

On August 10, 1942, German 6th Army had moved to the westbank of the Don, although strong Soviet resistance persisted in the north. On August 22, German forces establishedbridgeheads across the Don, which was crossed the next day, with panzers andmobile spearheads advancing across the remaining 36 miles of flat plains to Stalingrad. OnAugust 23, German 14th Panzer Division reached the VolgaRiver north of Stalingradand fought off Soviet counter-attacks, while the Luftwaffe began a bombingblitz of the city that would continue through to the height of the battle, whenmost of the buildings would be destroyed and the city turned to rubble.

On August 29, 1942, two Soviet armies (the 62nd and 64th)barely escaped being encircled by the German 4th Panzer Army and armored unitsof German 6th Army, both escaping to Stalingrad and ensuring that the battlefor the city would be long, bloody, and difficult.

On September 12, 1942, German forces entered Stalingrad, starting what would be a four-month longbattle. From mid-September to earlyNovember, the Germans, confident of victory, launched three major attacks tooverwhelm all resistance, which gradually pushed back the Soviets east towardthe banks of the Volga.

By contrast, the Soviets suffered from low morale, but werecompelled to fight, since they had no option to retreat beyond the Volga because of Stalin’s “Not one step back!”order. Stalin also (initially) refusedto allow civilians to be evacuated, stating that “soldiers fight better for analive city than for a dead one”. Hewould later allow civilian evacuation after being advised by his top generals.

Soviet artillery from across the Volgaand cross-river attempts to bring in Red Army reinforcements were suppressed bythe Luftwaffe, which controlled the sky over the battlefield. Even then, Soviet troops and suppliescontinued to reach Stalingrad, enough to keepup resistance. The ruins of the cityturned into a great defensive asset, as Soviet troops cleverly used the rubbleand battered buildings as concealed strong points, traps, and killingzones. To negate the Germans’ airsuperiority, Red Army units were ordered to keep the fighting lines close tothe Germans, to deter the Luftwaffe from attacking and inadvertently causingfriendly fire casualties to its own forces.

The battle for Stalingradturned into one of history’s fiercest, harshest, and bloodiest struggles forsurvival, the intense close-quarter combat being fought building-to-buildingand floor-to-floor, and in cellars and basements, and even in the sewers. Surprise encounters in such close distancessometimes turned into hand-to-hand combat using knives and bayonets.

By mid-November 1942, the Germans controlled 90% of thecity, and had pushed back the Soviets to a small pocket with four shallowbridgeheads some 200 yards from the Volga. By then, most of German 6th Army was lockedin combat in the city, while its outer flanks had become dangerouslyvulnerable, as they were protected only by the weak armies of its Axispartners, the Romanians, Italians, and Hungarians. Two weeks earlier, Hitler, believingStalingrad’s capture was assured, redeployed a large part of the Luftwaffe tothe fighting in North Africa.

Unbeknown to the Germans, in the previous months, the SovietHigh Command had been sending large numbers of Red Army formations to the northand southeast of Stalingrad. While only intending to use these units insporadic counter-attacks in support of Stalingrad, by November 1942, Stalin andhis top generals had reorganized these forces for a major counter-offensivecodenamed Operation Uranus involving an enormous force of 1.1 million troops,1,000 tanks, 14,000 artillery pieces, and 1,300 planes, aimed at cutting offand encircling German 6th Army and units of 7th Panzer Army in Stalingrad. German intelligence had detected the Sovietbuildup, but Hitler ignored the warning of his general staff, as by now he wasfirmly set on taking Stalingrad at all costs.

On November 19, 1942, the Soviet High Command launchedOperation Uranus, a double envelopment maneuver, with the Soviet SouthwesternFront attacking the Axis northern flank held by the Romanian 3rd Army. The next day, the Soviet Stalingrad Frontthrust from the south of the Axis flank, with the brunt of the attack fallingon Romanian 4th Army. The two Romanian Armies, lacking sufficient anti-tankweapons and supported only with 100 obsolete tanks, were overwhelmed by sheernumbers, and on November 22, the two arms of the Soviet pincers linked up atKalach. German 6th Army, elements of 4thPanzer Army, and remnants of the Romanian armies, comprising some250,000-300,000 troops, were trapped in a giant pocket in Stalingrad.

The German High Command asked Hitler to allow the trappedforces to make a break out, which was refused. Also on many occasions, General Friedrich Paulus, commander of German6th Army, made similar appeals to Hitler, but was turned down. Instead, on November 24, 1942, Hitler advisedGeneral Paulus to hold his position at Stalingraduntil reinforcements could be sent or a new German offensive could break theencirclement. In the meantime, thetrapped forces would be supplied from the air. Hitler had been assured by Luftwaffe chief Hermann Goering that the 700tons/day required at Stalingrad could bedelivered with German transport planes. However, the Luftwaffe was unable to deliver the needed amount, despitethe addition of more transports for the operation, and the trapped forces in Stalingrad soon experienced dwindling supplies of food,medical supplies, and ammunition. Withthe onset of winter and the temperature dropping to –30°C (–22°F), anincreasing number of Axis troops, yet without adequate winter clothing,suffered from frostbite. At this timealso, the Soviet air force had began to achieve technological and combat paritywith the Luftwaffe, challenging it for control of the skies and shooting downincreasing numbers of German planes.

Meanwhile, the Red Army strengthened the cordon aroundStalingrad, and launched a series of attacks that slowly pushed the trappedforces to an ever-shrinking perimeter in an area just west of Stalingrad.

In early December 1942, General Erich von Manstein,commander of the newly formed German Army Group Don, which was tasked withsecuring the gap between German Army Groups A and B, was ready to launch arelief operation to Stalingrad. Began on December 12 under Operation WinterStorm, German Army Group Don succeeded in punching a hold in the Soviet ringand advanced rapidly, pushing aside surprised Red Army units, and came towithin 30 miles of Stalingrad on December 19. Through an officer that was sent to Stalingrad,General Manstein asked General Paulus to make a break out towards Army GroupDon; he also sent communication to Hitler to allow the trapped forces to break out. Hitler and General Paulus both refused. General Paulus cited the lack of trucks andfuel and the poor state of his troops to attempt a break out, and that hiscontinued hold on Stalingrad would tie down large numbers of Soviet forceswhich would allow German Army Group A to retreat from the Caucasus.

On December 23, 1942, Manstein canceled the relief operationand withdrew his forces behind German lines, forced to do so by the threat ofbeing encircled by Soviet forces that meanwhile had launched Operation LittleSaturn. Operation Little Saturn was amodification of the more ambitious Operation Saturn, which aimed to trap GermanArmy Group A in the Caucasus, but was rapidly readjusted to counter GeneralManstein’s surprise offensive to Stalingrad. But Operation Little Saturn, the Sovietencirclement of Stalingrad, and the trapped Axis forces so unnerved Hitler thaton his orders, German Army Group A hastily withdrew from the Caucasusin late December 1942. German 17th Armywould continue to hold onto the Taman Peninsula in the Black Sea coast, and planned to usethis as a jump-off point for a possible future second attempt to invade the Caucasus.

Meanwhile in Stalingrad, byearly January 1943, the situation for the trapped German forces grew desperate. On January 10, the Red Army launched a majorattack to finally eliminate the Stalingradpocket after its demand to surrender was rejected by General Paulus. On January 25, the Soviets captured the lastGerman airfield at Stalingrad, and despite theLuftwaffe now resorting to air-dropping supplies, the trapped forces ran low onfood and ammunition.

With the battle for Stalingradlost, on January 31, 1943, Hitler promoted General Paulus to the rank of FieldMarshal, hinting that the latter should take his own life rather than becaptured. Instead, on February 2,General Paulus surrendered to the Red Army, along with his trapped forces,which by now numbered only 110,000 troops. Casualties on both sides in the battle of Stalingrad, one of thebloodiest in history, are staggering, with the Axis losing 850,000 troops, 500tanks, 6,000 artillery pieces, and 900 planes; and the Soviets losing 1.1million troops, 4,300 tanks, 15,000 artillery pieces, and 2,800 planes. The German debacle at Stalingrad and withdrawalfrom the Caucasus effectively ended Case Blue,and like Operation Barbarossa in the previous year, resulted in another Germanfailure.