Is There Still a Harvard Effect?

I remember the first and last time I attended a local Harvard Club event when I lived in Seattle. It was the Seattle club’s annual alumni interviewing information session, held on a rainy November evening at a lakeside estate in Yarrow Point (a Lake Washington neighborhood for the ultra-rich).

Let me be clear. I have no issue socializing with wealthy Americans. I’m not a Bolshevik. In fact, as a social scientist, I find their attempts to be “normal” and non-elitist highly amusing to observe. Everywhere else I have lived and studied on planet Earth, the rich are obnoxiously rich, don’t give a sh*t that you’re offended, and want you to never forget their wealth (e.g., India’s Ambani family). I understand the basics of dealing with these folks (i.e., don’t gasp when they cursorily mention some obscene service expenditure you would never pay for - like full-time, on-site housekeeping staff). I went to school with these folks from grade 7 through college. They’re just humans with far too much money. Again, not a Bolshevik.

I first recognized that most club members attending knew each other well. And the host never once greeted me after I signed in. I never even met him. Or I did, and I didn’t realize he was the host (!). It was like his home had been turned into a business convention ballroom where the gatekeeping had been done elsewhere. As I circulated awkwardly, I noticed the attendees were almost all in finance or hi-tech (shocker). They did not know what to talk to me about when I introduced myself as an anthropologist doing market research.

Shouldn’t you be a professor with an ‘important’ book plugged on NPR? They probably wondered to themselves. Have you achieved enough, James?

No one was overtly rude or dismissive that night. It’s the West Coast, so folks don’t slam judgmental statements at you like a snarky New York City party. It was simply an evening of polite non-connection. I was not high-achieving enough for these folks, even with my dusty PhD.

I mean, doesn’t everyone have a PhD, James?

I guess. 2.5 million PhD holders live in the U.S., and I once worked in an office with 12 of them. PSA - Don’t ever work in such a place, trust me. PhDs are anti-social and need lots of territory, like the male Andean Puma (i.e., 100-200 square miles). A Tesla Gigafactory is not large enough to contain 12 PhDs without growling and biting.

After the perfunctory presentation on how to help with alumni interviewing, I wrote down my name and contact info so that I could volunteer my time. I had low expectations. And no one followed up. Um, do I need to sign quicker next time? Is this too a competition?

Indifference was the ‘vibe’ I got that evening. Who are you, again? Oh, the anthropologist without a real job in anthropology. Sad. Should have gone to business school, my man.

WTF? Weren’t we all Harvard College graduates? And why are we all here measuring the length of our career penises in front of each other? Aren’t we supposed to be singing Fair Harvard and telling tall tales of eating 2 AM bowls of Chop Suey while under the influence?

Argh! Ivy League people are infuriatingly competitive sh*theads.

As I left, I congratulated myself for marrying outside the tribe.

I met a few College grads that night, but as I discovered in person, most Harvard Club members are only members because they have Harvard graduate degrees…mostly from Harvard Business School. Sigh.

I had been looking for the wrong club that evening, the one that wants Harvard College grads to interview applicants to Harvard College!! Outrageously elitist, I know! How dare I presume to have superior judgment to a mere HBS grad!

That evening clarified that the local Harvard Club was not really for all Harvard alumni. It was a club for the Seattle 1%, who happened to be Harvard alumni and mostly held MBAs. I'm sure many of these folks were nouveau riche, but the primal tribe was still class - class privilege linked to specific ultra-high-earning professions (or entrepreneurship). This party was chock full of the hard-charging, ultra-meritocratic elite, which David Brooks laments for ruining America in a recent Atlantic piece. (Brooks is the ‘low achieving’ NY Times journalist who graduated from the ‘humble and nonselective ’ University of Chicago)

Please don’t despair at how plebeian the Harvard Club has become; there is still a splash of the multi-generationally wealthy. You’ll always find one (with or without an MBA) nursing a Scotch in a chair, wondering what it’s like to “work” because you’ll lose your house if you don’t. What does that feel like?

That bizarre cocktail party of plate-mail-wearing W-2 Crusaders was not the first time I realized that my Harvard degree would not matter much for networking or that stumbling on a Harvard peer would not lead to anything remotely approaching the fist-bumpish reaction fellow “Badgers” from the University of Wisconsin give to each other.

Years earlier, my dissertation advisor (a Sarah Lawrence grad) could not have cared less about my Ivy League degree, OR she incorrectly assumed I was from the Harvard-educated 1% (a group she openly disdained as a left-wing anthropologist).

The more successful and typically employed you are as a Harvard College grad, the more likely you’re working somewhere where nowhere gives two sh*ts about your elite degree. The last place anyone cares about your Ivy League college degree is in fields like academia, management consulting, federal employment, Congress, philanthropy, or finance. These fields are awash in Ivy League degree holders, especially Congress, finance, and consulting.

As college attendance has exploded in the U.S., educational pedigree has ironically become increasingly meaningless among the very professional elite the Ivy League degree disproportionately sends its graduates to join. The Ivy League tribe itself is simply too vast now to create tight bonds of social trust. 500,000 living people have one of these degrees.

And we stand divided by far more critical identity markers. No, I’m not talking about race or gender. Sorry. I’m talking about the superior cultural power of professional tribes that transect alumni communities into a miniature version of the American caste system (i.e., a system of hierarchically arranged labor groups).

The triumph of professional identities in modern life has made elite alumni networking more or less pointless or simply an initial filtering device. Post-pedigree professional networking is vastly more powerful. This has certainly been true in my career. Again and again.

I suspect this is, in part, a logic of evolutionary human biology, in which humans gravitate to the most tightly aligned tribe they can muster in their social world. We really do prefer parish-sized social groups of 100-150…large enough to prevent incest but small enough so that we can know a ton about everyone.

As the upper-middle class has grown in proportion to the general population in the last fifty years, there are now simply too many ultra-highly educated people in close social proximity. And, if we are one of those professionals, we are more likely than ever to socialize entirely within this bizarre world of un-American Americans, chock full of Ivy League degrees.

So, our primitive human brains seek to find a smaller tribe. And our profession works better in terms of local social networks.

I can not establish it empirically, but the value of “Harvard” or “Yale” when networking within professions that don’t tend to have many of these punks is the most powerful. I’ve often experienced this power because I work in a non-elite industry vertical.

In the consumer packaged goods industry, for example, when asked where I went to school, the reaction, to my surprise, is usually flattering.

I found something eerily similar with regard to the PhD occasionally placed after my name. In my current industry, most non-Ivy grads are impressed and willing to call me “Dr.” until I ‘permit’ them not to do this. In academia or consulting, no one calls anyone else “Dr. Blah Blah.” Ever. Not anymore. In elite professions, harking back to prior educational achievements is gauche.

And here’s why.

Pedigree-based networking can NOT have much value in an urban culture focused on individual achievement in work and love. It really shouldn’t. You are only as powerful a social force as your most recent, significant achievement.

Always. Achieve. More.

Or face certain social death.

My expectation that rainy November evening at Yarrow Point was painfully antiquated because it rested on believing that my past should influence my access to current social resources.

Nope.

Only my most recent massive professional achievement. And I was languishing at the time. It was clear in my narrative and tone.

I have found that an Ivy League degree consistently impresses those in the general college-educated population—even the MAGA voter. It is a rare and well-cultivated national symbol pointing to someone likely to achieve a lot. Even, as in my case, it comes in an awkwardly wrapped package requiring loads of therapy.

The powerof this symbol can only be felt outside of the tribe itself, in the general population. Not as a networking tool but as a personal branding “badge.” You won’t get a phone call because you went to Harvard. You may do better on that call because Harvard and all the elite U.S. colleges tend to filter for a rarified bunch with better language skills than the average bloke. We tend to communicate very well in writing, verbally, or both.

But there’s something else.

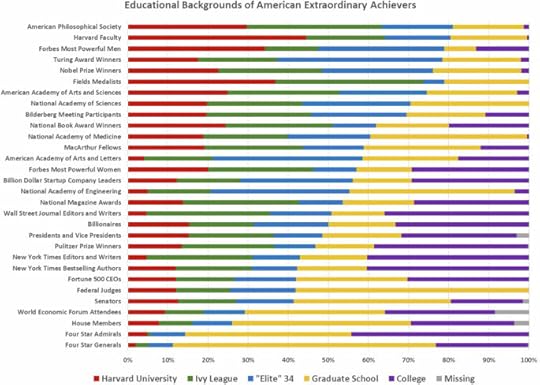

Ivy League, especially Harvard College graduates, are far more likely than the average peer to achieve extraordinary things marked off by most of us as culturally significant. This is the conclusion of a large national study published in Nature.

The extreme liberal arts luminaries of America tend to come from this tiny group of elite schools, not a typical college or university. However, if you’re a four-star general, no one cares that you went to Harvard or Princeton.

But, remember that this study is measuring over-representation in class of achievement.

This study does not prove that going to an Ivy League school guarantees extraordinary success. My network of Harvard friends from the Class of 1994 is a good case in point. I have classmates who have lost their lives to boring corporate careers that are of minimal interest to them. I also have U.S. District attorneys, voter registration activists, and published authors.

Yes, the definition of extraordinary achievement used in the study above is awfully narrow. But extreme behavior tends to reveal hidden dynamics of power and access in complex societies. This is an old social science technique. Measuring the margins.

It’s still debatable how much the Ivy League filters for people more likely to be high achievers or transform young adults into high achievers. I lean toward the filtering hypothesis myself.

Here’s a stray conclusion from the Nature study that I find quite revealing:

…the incredible influence of Harvard University—overrepresented among remarkable achievers by up to 80 times in a pattern one might call the Harvard Effect—is documented quantitatively here for the first time. Perhaps attending Harvard is not only a reflection of inputs, a gateway to critical educational and social experiences, or access to invaluable alumni networks, but also a more subtle treatment effect that increases one’s ambitions or expectations.1

It’s almost impossible to quantitatively analyze the latter hypothesis. Still, I strongly suspect it is at play because I’ve seen it present in the careers of my Harvard roommates and conspicuously absent in the careers of many of my business colleagues.

On more than one occasion, I’ve counseled someone informally, including a few paid clients, that “Your problem, [INSERT NAME], is that you lack Ivy League ego confidence.”

I’m not talking about cockiness, over-confidence, or delusional egoism. That is way too common among all men to be helpful here.

I mean a baseline confidence that makes you emotionally invincible against random idiots who want to challenge your contributions or potential in your chosen field.

Nope. You just remain quiet and smile internally at their folly. You may even decide they are correct, learn something, and improve! This would make them wrong for denying your potential.

Ivy Leaguers tend not to let others deny their potential. Ever.

As I’ve journeyed through the business world for the past 25 years, I’ve worked for both post-grad-educated professionals at huge multinationals and less well-educated business amateurs, acting as startup founders. The farther I get away from the professional classes, the more influential the “Harvard effect.” I’m referring specifically to the “ego confidence” effect.

People respond to unusual social confidence.

I’ve even worked for an owner who routinely mocked the Ivy League yet frequently hired its graduates (!) and promoted me five times in a row due to my “incredible potential.” (I just had to learn to control my mouth in the hair-trigger conversational business world.) Hmmm…

The same ego confidence led me to write on Substack weekly to a tiny audience, confident I would eventually accrue one. This Ivy League ego ties directly to a more general work trait that helps anyone stand out - persistence. It’s not a modern work trait at all. But, persistence is getting rarer, it seems.

The enemy of persistence is insecurity and self-doubt. Sadly, attacks on your credibility and career potential are also more frequent due to the horrendous spread of annual performance reviews (full of murky HR politics), internet-enabled screens, and the shameless trolls who troll those screens.

The Harvard effect is more internal, leading to an above-average rate of high cultural achievement wherever the odds are incredibly low of achieving anything…because people give up on themselves.

On a related note, I came across an excellent essay this week by who dives into his research on why the professional elite from which I hail tend to be the most dogmatic, tribalistic, and just plain weird folks out there.

Again, the link to extreme “ego confidence” is eerily present when you examine highly political behaviors like “dogma.” Read and support his new book, We Were Never Woke.

Symbolic Capital(ism)Smart People Are Especially Prone to Tribalism, Dogmatism and Virtue SignalingSymbolic capitalists – people who work in fields like education, consulting, finance, science and technology, arts and entertainment, media, law, human resources and so on – tend to have unusual political preferences and dispositions compared to most other Americans…Read more4 days ago · 178 likes · 23 comments · Musa al-Gharbi

Symbolic Capital(ism)Smart People Are Especially Prone to Tribalism, Dogmatism and Virtue SignalingSymbolic capitalists – people who work in fields like education, consulting, finance, science and technology, arts and entertainment, media, law, human resources and so on – tend to have unusual political preferences and dispositions compared to most other Americans…Read more4 days ago · 178 likes · 23 comments · Musa al-GharbiIf you like this essay, consider grabbing a copy of my recent book exploring the everyday experience of individualism as a way of life in the 21st century.

1

1