Increasing the chances of your picture book story being published. A quick-ish guide to getting and interpreting feedback by Juliet Clare Bell

(Or: You think you’ve finished your manuscript? Now let the wild rumpus start –in memory of legendary wild thing, Maurice Sendak, who died yesterday.)

There’s this funny thing with writing. You’ve got to be pretty bonkers to think that you can write a book that will be picked up by a publisher. Just look at these made-up stats:

And even once you’re published, the odds are against any single picture book manuscript of yours being picked up –other picture book authors I’ve asked often say approximately 20% of their manuscripts end up being published.

So how does anyone ever get from that huge pool of green to that titchy pool of blue? Unfortunately, the very thing that gets you all the way from that green pool to that red pool –deciding you can do it and actually finishing a story- is the same thing that can easily stop you from working your finished (draft of a) story up to a point where it’s going to get published...

You’ve written your story with passion and conviction. Your confidence, tenacity, steely determination, sheer bloody mindedness has kept you going from first thinking you might be able to do this to having actually written a story that you feel is worthy of being read countless times by a parent and child together. You needed bloody mindedness to get to this point (see Malachy’s post on Persistence).

But now you’ve got to keep it in check. You may feel like you’ve done it on your own till now and you don’t need anyone’s help. But you probably aren’t the best judge of how good your story is at this point...

And this is where feedback comes in...

Feedback –what’s it for?

This post already assumes that you’ve read trillions of picture books, practised and practised and practised, joined organisations like SCBWI and are really, really serious about getting your latest manuscript published.

Here are three possible reasons for wanting to get feedback (prior to sending your work to an editor or agent) on your picture book story:

[1] You want someone to tell you how much they love your story.

This is understandable, especially if you’re not published and you feel like you’re fighting for ‘permission’ to be doing what you’re doing. And if it feels good to show your story to family and friends, primed to like what you’ve done because you’ve done it, then that’s fine. It might give you confidence to carry on down a path that’s really tricky. But it’s not feedback. Not really (and if you send it to an editor, never mention the reaction of friends or family to your work. Ever);

[2] To slow yourself down before sending it to the person that really matters.

It’s so easy to send stuff out these days, if you can do it by email and this makes it even more tempting to send things out too early. Ever emailed a manuscript to a publisher slightly sooner than you’d have sent it if you’d had to print it out and take it to the post office first? (Me too...) Sending your manuscript to someone else first really helps satisfy the feeling of ‘getting something out there’ without it actually mattering too much. It’s really good cooling off time –and you actually get feedback from it;

[3] Because you want it to be the very best story it can be.

Accepting that other people might be more objective about your recently finished manuscript than you and that they might see ways of improving it, is bound to improve your chances of writing the best picture book you possibly can and having it picked up by an editor.

If you’re serious about your story, after all that hard work put into your manuscript don’t have an editor’s feedback as your first feedback. It’ll almost certainly be a form rejection or worse still, the feedback of silence...

So...

Prepare yourself for feedback. Grow an extra skin and stop thinking of your story as your ‘baby’...

Writing your story can be an intense experience. Some people refer to their manuscript as their baby. For all sorts of reasons, I think this is an unhelpful thing to do and reduces your likelihood of benefiting from feedback.

Writing your story can be an intense experience. Some people refer to their manuscript as their baby. For all sorts of reasons, I think this is an unhelpful thing to do and reduces your likelihood of benefiting from feedback.

In my previous life working in research at a university, I felt so sick at the thought of people reading drafts of papers I was writing that it often stopped me finishing them. I was so nervous of other people’s feedback and I could never stop feeling personal about what I’d written. It was a real waste –for the study I was working on and for me. I realised when I started out trying to write children’s books that I couldn’t do that again. Either I was going to learn to accept and make use of constructive criticism or I wasn’t going to get published, in which case, I wasn’t going to start writing.

It’s not easy to feel dispassionate about your work. But it certainly helps when getting feedback. Although we might like to think that everything we write is brilliant and already ready to go to an editor immediately, we are probably wrong. This makes it particularly hard to get feedback when you’re just starting out. Because what many new writers want is to be praised for what they’ve done –and they have achieved something important: finishing a story. If you’re not ready for real feedback, then put the manuscript away for a while until you can view it less personally. Then get it out again. Can you treat it as if it has been written by someone else? Do you want it to be the best it possibly can be and can you see that others might see things in it (or missing from it) that you may have overlooked? Will you manage not to be crushed by any suggestion of how it might be improved?

If you’re still too nervous to show anyone your work, don’t feel tempted to send it to an editor (at least, don’t act on that temptation).

Picture book feedback

Before deciding who to get feedback from, do consider the following:

[1] Ask any picture book editor: most picture book manuscripts that land on an editor’s desk are too long. Make sure the person you show your manuscript to is familiar with picture book length and knows that with a picture book manuscript every word has to earn its place. Picture book readers but not writers will probably not realise how few words there are in a well-crafted picture book. I still remember being shocked when I started out writing and typed up Julia Donaldson stories that seemed to have plenty of plot but were only 450 words... and then promptly started reducing my 1800 word-story down by three quarters...

[2] Many writers (as opposed to writer-illustrators) trying to write picture books don’t allow the pictures to do enough of the work in telling the story. Many readers of well-written picture books won’t realise that they’re reading half the story from the pictures. So a picture book critiquer needs to appreciate the importance of leaving enough room for the illustrations to do some of the work, and also the role of illustration notes –when to use them and when to leave them out.

The nature of picture books means that when you’re asking for feedback, you’re asking your critique to do two things: critique your story whilst at the same time imagining pictures that you’ve not provided for them.

So who should you get feedback from?

Family, friends and children?

Think carefully why you’re asking them. Their response is not likely to reflect how publishable your story is and they are very, very biased. They may want to please you, they may feel awkward about being critical or...

...they may just want a biscuit.

...they may just want a biscuit.

And unlike older fiction, they can’t read it as if it were published, as the pictures aren’t there yet. If you’re showing it to (your) children, remember, the ones for whom it’s actually written (pre-readers) won’t be able to read it for themselves, and older children who can read it might be more attracted to the stories that are actually too old for the intended age group. From my experience, they also prefer ones that don’t require any illustration notes...

Probably not ideal.

Critique groups with other writers?

This is where many children’s writers get feedback from. The SCBWI is great for providing feedback opportunities from other writers –both in face-to-face groups/events and online. I am a huge fan of the SCBWI (without which I very much doubt I’d be published) and I’d heartily recommend it to any children’s writer. There are other online picture book critique groups or opportunities to get feedback from another writer (for example 12 by 12 in ’12). Joining a critique group or meeting can be very nerve-wracking at first but it does get easier. (For information on setting up and running a critique group, click here.)

I know that everything I’ve written (both before I was published and since) has been improved –and sometimes transformed- by feedback from my fantastic critique partners.

Things worth considering: do you want to exchange manuscripts with children’s writers in general or just other picture book writers? It’s important that non-picture book writers know the constraints of the picture book but it can be good getting feedback from (and giving feedback to) other children’s writers, too. What’s important is what feedback they give and how well they give it. My experience of critique groups (I’m currently in three) has mostly been extremely positive, although occasionally I’ve had poor feedback (see my Banana Peelin’ story). And with practise I’ve become much better at receiving feedback (as well as giving it).

With practise, you will become tough and able to embrace feedback.

With practise, you will become tough and able to embrace feedback.

Possible disadvantages:

It can be very time-consuming (I probably critique over ten manuscripts per month –but then I get a lot of people critiquing mine back in return);

It can take a while to find the right critique group for you and for your own group to settle into something really mutually beneficial;

The quality of critiquing can be variable (so you need to learn how to make the most of different kinds of feedback from different people; but over time you change things until you’re happy with the group/s you’re in)

If you’re all unpublished, it’s possible that you’re all perpetuating the same errors in each other’s work that’s preventing you all from getting published;

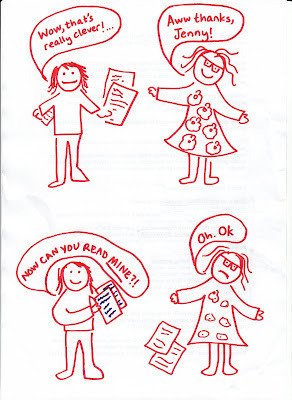

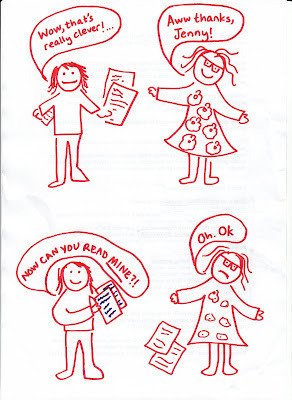

People may have their own agendas:

However, in my experience (and I've experienced different critique groups), this is rarely the case.

However, in my experience (and I've experienced different critique groups), this is rarely the case.

Paid for critiques?

Given how the book world has changed, many people who formerly worked in publishing houses or agencies now work as literary consultants, critiquing manuscripts (and some published authors and freelance writers do, too). If you’ve polished and polished your manuscript as much as you can -and had good feedback from fellow writers- and it’s still being rejected by publishers, then it may well be worthwhile paying for a critique.

Make sure you check out the freelancer first –do they know about picture books in particular? Do you like what they’ve written? Have they worked in a publishing house you know of? Do you know anyone else who’s used them and been happy with the service?

Possible disadvantages: it can be expensive;

Some freelancers will be better than others and it’s not always easy to know who to go with.

If you're in a good critique group, you may get a very similar critique free of charge.

But again, some freelance critiquers are excellent.

How to make the most of the feedback you’re given

[1] Try not to be defensive, and listen really, really carefully. For face-to-face critique groups, the Ursula LeGuin method means you can concentrate on listening to what others are saying rather than trying to defend yourself or your writing. It’s the same with a face-to-face editor meeting at a conference -don’t waste precious time defending your work when you’re there to hear how it might be improved.

The Ursula LeGuin method of running critique sessions (where the writer does not speak, but listens to everyone's feedback in turn) sounds scarier than it is. Honest.

[2] Ask. If you’re unsure about written feedback you’ve received, a fellow writer whose opinion you trust may be more objective in interpreting it (especially in the case of a personalised rejection from an editor). It’s often easier to see the negative side of feedback and overlook the positive. Recently, for example, I received some feedback from an editor. She said she really liked the title but then listed a number (quite a number) of things that didn’t work for her. I assumed that it was a straight rejection. Then she put a ‘however’... and proceeded to say how she really liked the character and that she’d be keen to see it again when I’d sorted out the things she didn’t think worked. It still felt negative but after showing it to a few people, I cut and pasted it and put all the positive things she said at the top and the negative things at the bottom and suddenly it seemed like much more positive feedback and something I could work through to provide her with a manuscript that she might really like.

[3] Is there consistency in your feedback from different people? You might want to dismiss parts of what people say but if a number of people are highlighting the same issues with your manuscript (or if different people pick up the same things on different manuscripts of yours), those issues probably need to be addressed.

[4] Learn to spot what’s important from the feedback

Some people will make suggestions as to how you can change your story. It may feel that they’re trying to rewrite it for you. This might be helpful to you or it might not, but it’s certainly very helpful to think about why they’re suggesting the change. Recently, an editor tentatively suggested I relocate my story to another part of the world. At first I thought I would and then realised why she was suggesting it –there was a problem with the story’s logic. Changing location would have sorted out that problem, but it would have changed other things in a way I wasn’t sure about. Now I’ve realised her thinking behind it, I can work out another way to sort out the story’s logic that fits with how I see my character.

[5] Take away different things from different people –after being in critique groups for years now, I know who’s really good at cutting my word count, or over-cutting, so I can compromise and take out half the words he’s suggesting (a word-slasher who isn’t personally attached to your favourite phrases that you’ve agonised over is invaluable to a picture book writer). I know who is good at spotting problems with structure; who is good at rhythm or tiny word changes (which can make such a difference in a picture book). You don’t have to act on all your feedback. Cherry pick the best and try and make the suggestions feel like your own.

[6] Don’t immediately start revising on the basis of feedback. Your initial reaction may be negative for a number of reasons –your pride might be slightly hurt; you might not like the way the feedback was presented; you might still be feeling quite defensive about your manuscript. Conversely, you might, like I often do, feel impatient to get going on a revision and initially agree with the suggestions made, especially if they come from someone you’re eager to please (like an editor or an agent). But unless you’ve given them a chance to settle, these changes may never feel like your own. Once you’ve read/had the feedback, sit on it for a while –days at least, possibly weeks, before making changes. If those suggested changes still don’t feel like your own, think carefully about whether that’s going to work. And never delete anything –you may change your mind.

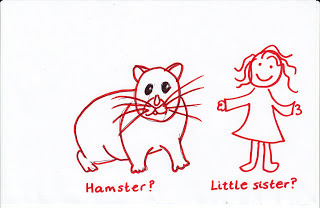

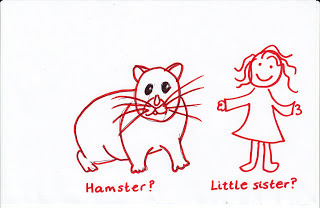

It never did quite work for me, changing my little sister into a hamster (as I was asked to do by an editor). But I tried... (and didn't delete the original).

As with writing, with practise you will get better at receiving feedback. Probably better to practise with people who aren't editors or agents so when you're in a situation with an editor or agent (at a conference one-to-one, or when they're responding to your work) you can make the very best of it. You'll almost certainly have a better manuscript to discuss with them, too.

The End.

(Hmmn, “The ending was particularly satisfactory...” –a genuine quote from my first ever picture book rejection. Now what exactly did she mean by that...?)

Juliet Clare Bell writes children’s books (Don’t Panic, Annika! illustrated by Jennifer E. Morris, Piccadilly Press, UK –other publishers overseas; Pirate Picnic, an early reader with Franklin Watts, August, 2012; The Kite Princess, illustrated by Laura-Kate Chapman, Barefoot Books, September, 2012) and amongst other things, runs critique events and groups for the British Isles SCBWI Chapter.

There’s this funny thing with writing. You’ve got to be pretty bonkers to think that you can write a book that will be picked up by a publisher. Just look at these made-up stats:

And even once you’re published, the odds are against any single picture book manuscript of yours being picked up –other picture book authors I’ve asked often say approximately 20% of their manuscripts end up being published.

So how does anyone ever get from that huge pool of green to that titchy pool of blue? Unfortunately, the very thing that gets you all the way from that green pool to that red pool –deciding you can do it and actually finishing a story- is the same thing that can easily stop you from working your finished (draft of a) story up to a point where it’s going to get published...

You’ve written your story with passion and conviction. Your confidence, tenacity, steely determination, sheer bloody mindedness has kept you going from first thinking you might be able to do this to having actually written a story that you feel is worthy of being read countless times by a parent and child together. You needed bloody mindedness to get to this point (see Malachy’s post on Persistence).

But now you’ve got to keep it in check. You may feel like you’ve done it on your own till now and you don’t need anyone’s help. But you probably aren’t the best judge of how good your story is at this point...

And this is where feedback comes in...

Feedback –what’s it for?

This post already assumes that you’ve read trillions of picture books, practised and practised and practised, joined organisations like SCBWI and are really, really serious about getting your latest manuscript published.

Here are three possible reasons for wanting to get feedback (prior to sending your work to an editor or agent) on your picture book story:

[1] You want someone to tell you how much they love your story.

This is understandable, especially if you’re not published and you feel like you’re fighting for ‘permission’ to be doing what you’re doing. And if it feels good to show your story to family and friends, primed to like what you’ve done because you’ve done it, then that’s fine. It might give you confidence to carry on down a path that’s really tricky. But it’s not feedback. Not really (and if you send it to an editor, never mention the reaction of friends or family to your work. Ever);

[2] To slow yourself down before sending it to the person that really matters.

It’s so easy to send stuff out these days, if you can do it by email and this makes it even more tempting to send things out too early. Ever emailed a manuscript to a publisher slightly sooner than you’d have sent it if you’d had to print it out and take it to the post office first? (Me too...) Sending your manuscript to someone else first really helps satisfy the feeling of ‘getting something out there’ without it actually mattering too much. It’s really good cooling off time –and you actually get feedback from it;

[3] Because you want it to be the very best story it can be.

Accepting that other people might be more objective about your recently finished manuscript than you and that they might see ways of improving it, is bound to improve your chances of writing the best picture book you possibly can and having it picked up by an editor.

If you’re serious about your story, after all that hard work put into your manuscript don’t have an editor’s feedback as your first feedback. It’ll almost certainly be a form rejection or worse still, the feedback of silence...

So...

Prepare yourself for feedback. Grow an extra skin and stop thinking of your story as your ‘baby’...

Writing your story can be an intense experience. Some people refer to their manuscript as their baby. For all sorts of reasons, I think this is an unhelpful thing to do and reduces your likelihood of benefiting from feedback.

Writing your story can be an intense experience. Some people refer to their manuscript as their baby. For all sorts of reasons, I think this is an unhelpful thing to do and reduces your likelihood of benefiting from feedback.In my previous life working in research at a university, I felt so sick at the thought of people reading drafts of papers I was writing that it often stopped me finishing them. I was so nervous of other people’s feedback and I could never stop feeling personal about what I’d written. It was a real waste –for the study I was working on and for me. I realised when I started out trying to write children’s books that I couldn’t do that again. Either I was going to learn to accept and make use of constructive criticism or I wasn’t going to get published, in which case, I wasn’t going to start writing.

It’s not easy to feel dispassionate about your work. But it certainly helps when getting feedback. Although we might like to think that everything we write is brilliant and already ready to go to an editor immediately, we are probably wrong. This makes it particularly hard to get feedback when you’re just starting out. Because what many new writers want is to be praised for what they’ve done –and they have achieved something important: finishing a story. If you’re not ready for real feedback, then put the manuscript away for a while until you can view it less personally. Then get it out again. Can you treat it as if it has been written by someone else? Do you want it to be the best it possibly can be and can you see that others might see things in it (or missing from it) that you may have overlooked? Will you manage not to be crushed by any suggestion of how it might be improved?

If you’re still too nervous to show anyone your work, don’t feel tempted to send it to an editor (at least, don’t act on that temptation).

Picture book feedback

Before deciding who to get feedback from, do consider the following:

[1] Ask any picture book editor: most picture book manuscripts that land on an editor’s desk are too long. Make sure the person you show your manuscript to is familiar with picture book length and knows that with a picture book manuscript every word has to earn its place. Picture book readers but not writers will probably not realise how few words there are in a well-crafted picture book. I still remember being shocked when I started out writing and typed up Julia Donaldson stories that seemed to have plenty of plot but were only 450 words... and then promptly started reducing my 1800 word-story down by three quarters...

[2] Many writers (as opposed to writer-illustrators) trying to write picture books don’t allow the pictures to do enough of the work in telling the story. Many readers of well-written picture books won’t realise that they’re reading half the story from the pictures. So a picture book critiquer needs to appreciate the importance of leaving enough room for the illustrations to do some of the work, and also the role of illustration notes –when to use them and when to leave them out.

The nature of picture books means that when you’re asking for feedback, you’re asking your critique to do two things: critique your story whilst at the same time imagining pictures that you’ve not provided for them.

So who should you get feedback from?

Family, friends and children?

Think carefully why you’re asking them. Their response is not likely to reflect how publishable your story is and they are very, very biased. They may want to please you, they may feel awkward about being critical or...

...they may just want a biscuit.

...they may just want a biscuit.And unlike older fiction, they can’t read it as if it were published, as the pictures aren’t there yet. If you’re showing it to (your) children, remember, the ones for whom it’s actually written (pre-readers) won’t be able to read it for themselves, and older children who can read it might be more attracted to the stories that are actually too old for the intended age group. From my experience, they also prefer ones that don’t require any illustration notes...

Probably not ideal.

Critique groups with other writers?

This is where many children’s writers get feedback from. The SCBWI is great for providing feedback opportunities from other writers –both in face-to-face groups/events and online. I am a huge fan of the SCBWI (without which I very much doubt I’d be published) and I’d heartily recommend it to any children’s writer. There are other online picture book critique groups or opportunities to get feedback from another writer (for example 12 by 12 in ’12). Joining a critique group or meeting can be very nerve-wracking at first but it does get easier. (For information on setting up and running a critique group, click here.)

I know that everything I’ve written (both before I was published and since) has been improved –and sometimes transformed- by feedback from my fantastic critique partners.

Things worth considering: do you want to exchange manuscripts with children’s writers in general or just other picture book writers? It’s important that non-picture book writers know the constraints of the picture book but it can be good getting feedback from (and giving feedback to) other children’s writers, too. What’s important is what feedback they give and how well they give it. My experience of critique groups (I’m currently in three) has mostly been extremely positive, although occasionally I’ve had poor feedback (see my Banana Peelin’ story). And with practise I’ve become much better at receiving feedback (as well as giving it).

With practise, you will become tough and able to embrace feedback.

With practise, you will become tough and able to embrace feedback.Possible disadvantages:

It can be very time-consuming (I probably critique over ten manuscripts per month –but then I get a lot of people critiquing mine back in return);

It can take a while to find the right critique group for you and for your own group to settle into something really mutually beneficial;

The quality of critiquing can be variable (so you need to learn how to make the most of different kinds of feedback from different people; but over time you change things until you’re happy with the group/s you’re in)

If you’re all unpublished, it’s possible that you’re all perpetuating the same errors in each other’s work that’s preventing you all from getting published;

People may have their own agendas:

However, in my experience (and I've experienced different critique groups), this is rarely the case.

However, in my experience (and I've experienced different critique groups), this is rarely the case.Paid for critiques?

Given how the book world has changed, many people who formerly worked in publishing houses or agencies now work as literary consultants, critiquing manuscripts (and some published authors and freelance writers do, too). If you’ve polished and polished your manuscript as much as you can -and had good feedback from fellow writers- and it’s still being rejected by publishers, then it may well be worthwhile paying for a critique.

Make sure you check out the freelancer first –do they know about picture books in particular? Do you like what they’ve written? Have they worked in a publishing house you know of? Do you know anyone else who’s used them and been happy with the service?

Possible disadvantages: it can be expensive;

Some freelancers will be better than others and it’s not always easy to know who to go with.

If you're in a good critique group, you may get a very similar critique free of charge.

But again, some freelance critiquers are excellent.

How to make the most of the feedback you’re given

[1] Try not to be defensive, and listen really, really carefully. For face-to-face critique groups, the Ursula LeGuin method means you can concentrate on listening to what others are saying rather than trying to defend yourself or your writing. It’s the same with a face-to-face editor meeting at a conference -don’t waste precious time defending your work when you’re there to hear how it might be improved.

The Ursula LeGuin method of running critique sessions (where the writer does not speak, but listens to everyone's feedback in turn) sounds scarier than it is. Honest.

[2] Ask. If you’re unsure about written feedback you’ve received, a fellow writer whose opinion you trust may be more objective in interpreting it (especially in the case of a personalised rejection from an editor). It’s often easier to see the negative side of feedback and overlook the positive. Recently, for example, I received some feedback from an editor. She said she really liked the title but then listed a number (quite a number) of things that didn’t work for her. I assumed that it was a straight rejection. Then she put a ‘however’... and proceeded to say how she really liked the character and that she’d be keen to see it again when I’d sorted out the things she didn’t think worked. It still felt negative but after showing it to a few people, I cut and pasted it and put all the positive things she said at the top and the negative things at the bottom and suddenly it seemed like much more positive feedback and something I could work through to provide her with a manuscript that she might really like.

[3] Is there consistency in your feedback from different people? You might want to dismiss parts of what people say but if a number of people are highlighting the same issues with your manuscript (or if different people pick up the same things on different manuscripts of yours), those issues probably need to be addressed.

[4] Learn to spot what’s important from the feedback

Some people will make suggestions as to how you can change your story. It may feel that they’re trying to rewrite it for you. This might be helpful to you or it might not, but it’s certainly very helpful to think about why they’re suggesting the change. Recently, an editor tentatively suggested I relocate my story to another part of the world. At first I thought I would and then realised why she was suggesting it –there was a problem with the story’s logic. Changing location would have sorted out that problem, but it would have changed other things in a way I wasn’t sure about. Now I’ve realised her thinking behind it, I can work out another way to sort out the story’s logic that fits with how I see my character.

[5] Take away different things from different people –after being in critique groups for years now, I know who’s really good at cutting my word count, or over-cutting, so I can compromise and take out half the words he’s suggesting (a word-slasher who isn’t personally attached to your favourite phrases that you’ve agonised over is invaluable to a picture book writer). I know who is good at spotting problems with structure; who is good at rhythm or tiny word changes (which can make such a difference in a picture book). You don’t have to act on all your feedback. Cherry pick the best and try and make the suggestions feel like your own.

[6] Don’t immediately start revising on the basis of feedback. Your initial reaction may be negative for a number of reasons –your pride might be slightly hurt; you might not like the way the feedback was presented; you might still be feeling quite defensive about your manuscript. Conversely, you might, like I often do, feel impatient to get going on a revision and initially agree with the suggestions made, especially if they come from someone you’re eager to please (like an editor or an agent). But unless you’ve given them a chance to settle, these changes may never feel like your own. Once you’ve read/had the feedback, sit on it for a while –days at least, possibly weeks, before making changes. If those suggested changes still don’t feel like your own, think carefully about whether that’s going to work. And never delete anything –you may change your mind.

It never did quite work for me, changing my little sister into a hamster (as I was asked to do by an editor). But I tried... (and didn't delete the original).

As with writing, with practise you will get better at receiving feedback. Probably better to practise with people who aren't editors or agents so when you're in a situation with an editor or agent (at a conference one-to-one, or when they're responding to your work) you can make the very best of it. You'll almost certainly have a better manuscript to discuss with them, too.

The End.

(Hmmn, “The ending was particularly satisfactory...” –a genuine quote from my first ever picture book rejection. Now what exactly did she mean by that...?)

Juliet Clare Bell writes children’s books (Don’t Panic, Annika! illustrated by Jennifer E. Morris, Piccadilly Press, UK –other publishers overseas; Pirate Picnic, an early reader with Franklin Watts, August, 2012; The Kite Princess, illustrated by Laura-Kate Chapman, Barefoot Books, September, 2012) and amongst other things, runs critique events and groups for the British Isles SCBWI Chapter.

Published on May 09, 2012 14:26

No comments have been added yet.