Corruption, Cults, and Collapse: Voters Reject Japan’s Ruling Party in Major Election Blow

The sins of deceased ex-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe: the slush fund, the failed economic policies, and the ties to the unification church came back to haunt his party.

The sins of deceased ex-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe: the slush fund, the failed economic policies, and the ties to the unification church came back to haunt his party. In a not-so-surprising twist that has Japan’s ruling party licking its wounds, the 2024 lower house election results show the ruling coalition crumbling to pieces. After decades of near-uninterrupted dominance since 1955, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP)–which is neither liberal nor democratic–couldn’t escape the weight of its own corruption scandals, failed economic policies, and, perhaps most damningly, its ties to the Unification Church, a group detested by the Japanese public. You won’t hear the Japanese press write much about that aspect of their losses, because the church has begun suing newspapers and media critical of their activities.

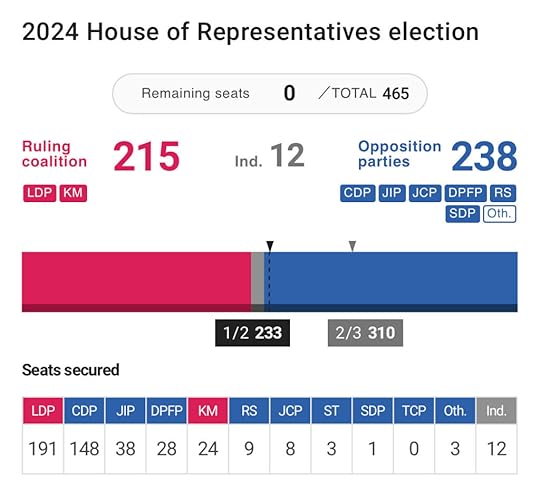

The LDP and their coalition partner Komeito needed 233 seats to hold onto power–they ended up with 214. The LDP itself shrank to 191 seats and their staunchly liberal opposition, the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan scored 148, making them the largest opposition party in the lower house of Japan’s Parliament.

The Liberal Democratic Party is composed of many different factions, much like the Yamaguchi-gumi, Japan’s largest yakuza group (founded in 1915) also has various factions vying for power.

The de facto Abe faction, once the shining star of the party, has been irreparably tainted–and were the biggest losers. Former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s assassination in 2022 was a political earthquake, but the revelations that followed shook the LDP to its core. Turns out, the beloved leader wasn’t just working on behalf of the people; he and his inner circle were knee-deep in shady dealings with the notorious Unification Church, a group reportedly known for exploiting its members and funneling cash into political coffers.

Economically, the so-called success of Abenomics, which was supposed to lift Japan from its decades-long stagnation, has been revealed to be largely smoke and mirrors—based on falsified data. What it left behind was a gaping wealth gap, inflation that made daily life increasingly difficult, and wages that hadn’t budged in years. Former Prime Minister Fumio Kishida promised to change gears but kept the same failed policies in place. The people of Japan had simply had enough.

This election isn’t just a loss for the LDP; it’s a referendum on a political system that’s been slowly eroding. The rise of the opposition, led by the CDP with 148 seats, signals a shift in public sentiment. Parties like the Japan Innovation Party (JIP) and the Democratic Party for the People (DPFP) are now positioned to play larger roles in shaping Japan’s future.

The LDP’s downfall can be seen as a microcosm of the failures plaguing long-standing political regimes worldwide: arrogance, corruption, and an inability to adapt to the needs of a changing society. When power is too concentrated for too long, it begins to rot from the inside out.

The unholy alliance between the LDP and the Unification Church was just the tipping point. This election marks a dramatic turn in Japanese politics, one that may finally bring the long-simmering dissatisfaction with the ruling party to a boil.

The Fall of Hakubun Shimomura Is A Microcosm Of The Greater Problem

In what can only be described as a fall from grace too ironic to script, Hakubun Shimomura, a former education minister, has found himself on the wrong side of a ballot box. After nine consecutive terms in the Tokyo 11th district, Shimomura lost his seat to Yukihiko Akutsu of the Constitutional Democratic Party, and if you’re inclined to celebrate underdog victories, hold your applause—there’s more than just a campaign gaffe or two at play here.

The 70-year-old Shimomura, once a darling of the political elite, couldn’t withstand the mounting scandals that had come to define his career like the pins in a voodoo doll. His name is inextricably linked to an “envelopes-under-the-table” type of affair—let’s call it the “Secret Cash Scandal” (see below). And when you’ve got a moniker like that hanging over you, even the most forgiving electorate starts to ask uncomfortable questions. He had been banned from running on the LDP’s proportional representation list, the political equivalent of being put in the corner with a dunce cap.

There’s something so textbook about his fall, a perfect encapsulation of what happens when the political machine that got you to the top starts churning in reverse. Shimomura is not the only LDP politician whose career has been sabotaged by scandals like these, but his trajectory feels almost like a satire of itself. The former Minister of Education, was once linked to a yakuza associate—who specialized in running school-girl themed sex-shops. He promised to investigate the links between the vice-chairman of Japan’s Olympic Committee and the Yamaguchi-gumi (yakuza group) and then buried the investigation.

He’s the guy who survived nearly three decades of political intrigue, only to be unseated in the twilight of his career by a candidate who spent the better part of two years languishing in relative obscurity. The only thing missing from the narrative is a Greek chorus chanting, “We told you so!”

To add to the irony, Shimomura had been one of the key figures connected to the controversy surrounding the Unification Church, the religious organization formerly known as the Moonies. If you recall, it was his office that oversaw the approval of the group’s name change back in 2015. At the time, it probably seemed like a small procedural matter, but in hindsight, it was the kind of thing that sticks to your political record like gum on a shoe. The ties to the Unification Church not only haunted his campaign but turned the public perception of him into that of a shady backroom dealer—a villain too out of touch to be reformed.

Throughout the campaign, Shimomura made quite the spectacle of apologizing, visiting over 8,000 homes in what one could call his “sincerity tour.” Picture him with his head bowed, muttering apologies like a fallen samurai seeking redemption. It’s a dramatic image, but it wasn’t enough. Shimomura was seen as the embodiment of the LDP’s worst habits—backroom deals, cozying up to questionable organizations, and a blatant disregard for transparency, all of which have soured the electorate’s taste for the party.

These types of scandals are not isolated incidents but rather emblematic of a larger systemic rot within the political hierarchy. Shimomura’s fall is just one more example of the self-inflicted wounds the LDP has suffered, and it raises the question of whether these political titans ever learn. It’s not the scandals themselves that take politicians down, but rather the perception of arrogance and invincibility that seems to precede their downfall.

If we zoom out, Shimomura’s defeat isn’t just about one man’s loss. It’s a microcosm of the deeper issues the Liberal Democratic Party of Japan (and frankly, many parties around the world) face in trying to retain the public’s trust while navigating their own internal chaos. The public may forgive a mistake or two, but when the perception of corruption becomes the rule rather than the exception, well, voters decide it’s time for a change.

Their coalition partner, Komeito, didn’t fare well either. Komeito is the political arm of the buddhist organization Soka Gakkai which some have called a cult. It was revealed this year that their spiritual leader, Ikeda Daisaku–who had not been seen in public for over a decade–was actually dead. When he really died, no one knows. Ikeda vanished from public view around the time former Yamaguchi-gumi yakuza boss, Tadamasa Goto, published his biography Habakaringara. In that book, he bragged that he had been doing the dirty work for Soka Gakkai and Ikeda for decades.

The Curse of Shinzo Abe

To truly understand the political implosion of Hirofumi Shimomura and his comrades in this election, you have to consider the broader context of the collapse of the Abe faction and the wreckage left in its wake. For nearly a decade, Shinzo Abe and his loyalists operated with the confidence of autocrats, not just running Japan, but crushing dissent, controlling narratives, and scandalizing the political system like it was part of the job description. Abe himself, until his shocking assassination, wielded immense power behind the scenes, often suppressing freedom of the press and/or corrupting top dogs in the media by wining and dining them. But what finally broke through that iron grip was a revelation so insidious that even Japan’s famously forgiving electorate had had enough.

After Abe’s assassination, the floodgates opened, and it became clear that the prime minister—along with many high-ranking members of the LDP—had been intimately connected with the Unification Church. Yes, that Unification Church, the religious group (or, as most people in Japan prefer to call it, a cult) that has been despised for decades. The fact that Abe and his cronies were not just affiliated with the group but in bed with them on a scale that made voters’ skin crawl sent shockwaves through the nation. It wasn’t just bad optics—it was the epitome of the kind of shady backroom deals that defined the Abe era.

If you’re a student of history, you know that the Liberal Democratic Party was founded with yakuza money by war-time profiteer, Kodama Yoshio and war-criminal Nobosuke Kishi, Abe’s grandfather. From bad seeds, bad things grow. . What should be pointed out is that Abe’s folly wasn’t just a case of a politician playing footsie with an unsavory organization—it was emblematic of the entire Abe faction’s disdain for transparency and democracy. He also cuddled up to sexist right-wing cult, Nippon Kaigi, which opposes many policies that the majority of the Japanese public supports. , But it was the Unification Church link that really damaged his legacy. In fact, his assassin targeted Abe precisely to bring those ties to light. By the time Kishida decided to give Abe a lavish state funeral, 80% of the public opposed the waste of money.

With the public now acutely aware of just how deeply the LDP had been corrupted by its dealings with the Unification Church, the house of cards began to collapse.

As Shimomura learned the hard way, you can only apologize for so long before voters stop listening. His relentless campaign of mea culpas—visiting 8,000 homes to personally apologize—seems quaint when stacked up against the larger issues haunting the LDP. People weren’t just angry at him; they were angry at the system that allowed someone like him to stay in power for nearly three decades.

Abe’s so-called economic success—Abenomics—was supposed to be his legacy. But in reality, it was a carefully crafted mirage built on falsified data from the government. The very foundation of Japan’s economic recovery during his tenure was shaky at best, propped up by manipulation and spin. Wages stagnated, inflation soared, and the gap between rich and poor grew ever wider. Those at the top saw the benefits, while millions were left in a limbo of rising costs and shrinking opportunities. And as Shimomura’s loss shows, voters have reached their breaking point.

This election has been a reckoning not just for Shimomura, but for anyone associated with the Abe faction. Across the board, candidates tied to Abe have fared poorly. His assassination may have removed the man, but the shadow of his scandals, his connections to the Unification Church, and his autocratic tendencies lingers, leaving the LDP scrambling to find a new identity amid the debris.

Shimomura’s downfall is symbolic of what happens when a party—and a political faction—becomes too comfortable in its own corruption. The people of Japan, facing rising inflation, stagnant wages, and an ever-widening wealth gap, have had enough. The LDP has been in power for so long that it forgot it was supposed to serve the public, not control it. And now, as the Abe era truly comes to a close, Shimomura and other Abe cronies are left standing on the street, microphones in hand, wondering where it all went wrong.

Anpanman isn’t stupid: Ishiba’s Power-Play

Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba has a strange following among Japanese women who think he’s cute, like a mascot. He does resemble Anpan-man, the pastry hero beloved by children. But he’s not a child. At the heart of the LDP’s electoral implosion was a bold move by the current Prime Minister and former defense minister, whose power-play may have gone unnoticed by many. Ishiba, perhaps sensing that the political tides were turning, refused to grant party backing to LDP candidates who had been caught red-handed in the political funds scandal. More notably, he barred these scandal-tainted figures from being listed on the proportional representation roster*, the lifeboat that could have saved many from their inevitable loss in single-seat elections. Without this safety net, politicians like Hirofumi Shimomura found themselves stranded.

Ishiba’s strategy was clear: cut the party’s losses and purge the taint of corruption, even if it meant temporarily weakening the LDP’s grip on power. It was a calculated gamble, one that not only distanced the party from its most scandal-ridden figures but also conveniently eliminated many of his own political rivals within the LDP. The result? A weakened party, stripped of its old guard, and left to face an emboldened opposition. In the short term, this maneuver accelerated the LDP’s downfall and handed a decisive victory to the opposition. Whether this will be remembered as a tactical masterstroke that ultimately saved the party, or the final nail in the coffin of the Abe-era LDP, remains to be seen.

Results

2024 House of Representatives Election

• LDP (Liberal Democratic Party): 191 seats secured (132 in constituencies and 59 in proportional representation).

• CDP (Constitutional Democratic Party): 148 seats secured (104 in constituencies and 44 in proportional representation).

• JIP (Japan Innovation Party): 38 seats secured.

• DPFP (Democratic Party for the People): 28 seats secured.

• KM (Komeito): 24 seats secured.

• RS (Reiwa Shinsengumi): 9 seats secured.

• JCP (Japanese Communist Party): 8 seats secured.

• ST (Socialist Party): 3 seats secured.

• SDP (Social Democratic Party): 1 seat secured.

• TCP (Tokyo Citizens Party): 0 seats secured.

• Other: 3 seats.

• Independent candidates: 12 seats.

*In Japan, during elections, people fill out two ballots. One for the candidate in their region and another voting for a political party. The number of party votes determines a certain number of representatives the party gets in office. The roster created by the party gives a chance for politicians who lose “the popular vote” to still stay in office or be put there in the first place. The names of the candidates and party must be handwritten.