Returning Home: The Dakota’s Journey Back to Minnesota After Forced Exile

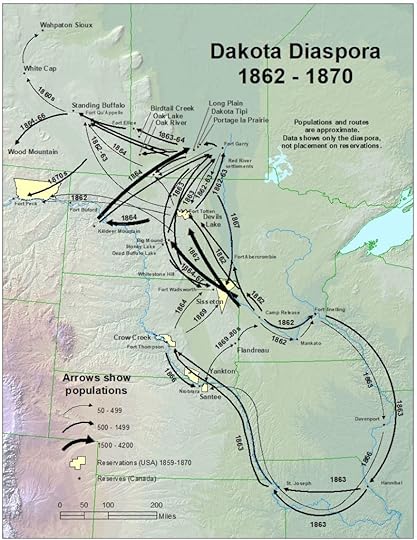

Map of the Dakota diaspora from 1862-1870, courtesy Bob Werner. From the Minnesota Historical Society.

Map of the Dakota diaspora from 1862-1870, courtesy Bob Werner. From the Minnesota Historical Society.

On February 21, 1863, the U.S. Congress passed the Winnebago Removal Act, followed by the Sioux-Dakota Removal Act on March 3, 1863. These Acts, a response to the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862, allowed the President to relocate the Winnebago (Ho-Chunk) and Dakota “beyond the limits of any State” and specifically removed them from “the State of Minnesota.” These Acts marked the peak of a long effort by the U.S. government to control Native peoples and take their land and resources.

Despite these Acts, today there are eleven federally recognized Indian Tribes in Minnesota, including four Dakota-Sioux communities. But how did the Dakota return to their homeland after their forced exile? A full understanding of their return and community growth requires extensive study, but let’s briefly explore the re-establishment of Dakota communities in Minnesota after the Removal Acts.

Although the Dakota were to be moved “beyond the limits of any State,” the U.S. government distinguished between “hostile” and “friendly” Dakota. In the 1866 Annual Report to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Indian agent H.P. Van Cleeve noted a friendly Sioux settlement at Lake Hendricks, near the Minnesota/South Dakota border, and others to the southwest. Van Cleeve described these Dakota as “efficient and trustworthy,” viewing them as “advance scouts” protecting Minnesota from “hostile Sioux” further west. These Dakota could stay in Minnesota as long as they remained loyal to U.S. interests.

According to the Lower Sioux Indian Community, many families returned to their homeland, and those loyal to the U.S. during the Outbreak were allowed to stay on Minnesota lands designated for the Dakota under treaties. The 1883 census recorded six Dakota families at Redwood, the site of the Lower Sioux Indian Community. In 1884, Good Thunder, a former Hazelwood Republic member, returned to the Lower Sioux and bought 80 acres of land. Charles Lawrence purchased the neighboring 80 acres, and soon a small colony formed, including other Dakotas who had managed to survive in Minnesota.

The Mendota Mdewakanton Dakota Tribal Community reports that in 1886, government funds helped a group of Dakota buy land at Prior Lake. This is likely the same land mentioned by Ronald G. Stover in his essay Minnesota Dakota Diaspora, where the federal government documented the actions of 208 Dakota and bought three tracts of land for them and their descendants. In 1889, the U.S. Government passed the Appropriations Act, allowing “Indians who were loyal to the United States during the Sioux Outbreak in August 1862 in Minnesota” to return home and receive land. By 1899, as reported by the Mendota Mdewakanton Dakota Tribal Community, seventy Dakota people lived in Hennepin County.

While much has changed since then, it’s notable that earlier this year, the State of Minnesota returned 14,000 acres of land to the Upper Sioux Indian Community. Though a small act of reparations, it is a reversal of the 1863 Removal Acts that aimed to permanently exile Dakota peoples from their homeland. As we continue to reflect on our history and its legacies, I hope more reparations can be made and official removal acts can be justifiably annulled.

Sources:

Sioux-Dakota Removal Acts, Minnesota Legal History Project

This Day in History: The Dakota Exile, May 4-5, Healing Minnesota Stories

H.P. Van Cleve to Governor William R. Marshall, May 19, 1866, Archive.org

Cansa’yapi / Lower Sioux Indian Community, Minnesota Indian Affairs Council

Wolfchild v. U.S., National Indian Law Library, NARF, CaseText

Minneapolis History is Really Sioux History, Mendota Mdewakanton Dakota Tribal Community, Mendota Dakota

Minnesota Dakota Diaspora, Ronald G. Stover, South Dakota State University, OSU Library

After 161 years, land was officially returned to the Upper Sioux Community by Meliss Olson, March 15, 2024, MPR News

About the Author

Colin Mustful is a celebrated author and historian whose novel Reclaiming Mni Sota recently won the Midwest Book Award for Literary/Contemporary/Historical Fiction. With a Master of Arts in history and a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing, Mustful has penned five historical novels that delve into the complex eras of settler-colonialism and Native American displacement. He is also the founder and editor of History Through Fiction, an independent press dedicated to publishing historical narratives rooted in factual events and characters. Committed to bringing significant historical tales to light, Mustful collaborates with authors as a traditional and hybrid publisher. Residing in Minneapolis, Minnesota, he enjoys running, playing soccer, and believes deeply in the power of understanding history to shape a just and sustainable future.