What Else Can Haiku Do?

I went on a tear last night—a tear of modernist poetry. Imagism, in particular.

It actually didn’t start out with haiku, even though it could have. I’m not exactly sure why this foreign poetry style from the 17th century is my favorite, but it is. I was actually reading an article in Triangle magazine, by Henry Shukman on Zen and art.

For better or worse, “Zen and the Art of…” has become a phrase that, like “Catch-22,” gets bandied about in all kinds of contexts. Zen and the Art of Changing Diapers, Zen and the Art of Casino Gaming, Zen and the Art of Faking It—there are now literally hundreds of books with “Zen and the Art of…” in the title, all presumably taking their cue from Robert Pirsig’s huge 1970s bestseller, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance…

The article is on “why the relationship between Zen and art is neither as simple or obvious as these cliché implies.” I said to my husband, “I really wish this article was longer, because it’s getting into some complicated stuff, that covers centuries. How can one article get from ancient Zen centers, and the art involved with them, to 1970s philosophy?”

Probably better than this blog entry can, but hey. Let’s try to trace it back a little bit.

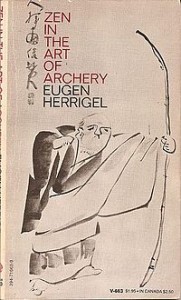

Motorcycle maintenance dude was referencing, “Zen in the Art of Archery,” by German philosopher Eugen Herrigel, who lived in Japan for a bit and is credited with introducing Zen to Europe after WWII. Except, he kinda got Zen wrong because he learned it from Master Kenzô, who did teach archery, but, wasn’t a teacher or practitioner of Zen Buddhism. Whoops.

Motorcycle maintenance dude was referencing, “Zen in the Art of Archery,” by German philosopher Eugen Herrigel, who lived in Japan for a bit and is credited with introducing Zen to Europe after WWII. Except, he kinda got Zen wrong because he learned it from Master Kenzô, who did teach archery, but, wasn’t a teacher or practitioner of Zen Buddhism. Whoops.

I can’t judge the guy too harshly. Maybe it wasn’t his goal to start a Zen craze in Europe. He certainly couldn’t have foreseen, “Zen and the Art of Competitive Eating.”

It just goes to show you how easy it is to mess it up when you try to adapt or translate art from another culture.

But I don’t think it’s bad to try.

The purpose of haiku, as I see it in the western world, isn’t to create a perfect capsule of Japanese culture. Nor is it to butcher haiku’s traditional tenets and strengths. It’s something in-between. I think you can learn from other cultures, and the art forms especially within those cultures, to stretch your own views of the world. Give them their due and take care not to co-opt, but, by all means, keep learning.

Somewhere along my tear, I moved from the article to reading about Ezra Pound, and the Imagist poetry movement he made famous. Pound, too, studied Japanese art forms, especially tanka. “Hey!” I told myself, “I’ve read him. I have the Personae anthology downstairs. Man, that guy was a self-absorbed douche. How the hell was that book influenced by tanka?” It wasn’t really. His imagist work came after.

Imagism (popularized by Pound, H.D., and Richard Aldington) was a short-lived, but highly influential poetry movement. It, itself, was influenced by Japanese poetry, as well as the Greek lyric poetry of Sappho (which I also have downstairs), and the French/Russian/Belgian Symbolism movement. It has three principles:

1. Direct treatment of the “thing” whether subjective or objective.

2. To use absolutely no word that does not contribute to the presentation.

3. As regarding rhythm: to compose in the sequence of the musical phrase, not in sequence of a metronome.

Ahhhh…. lovely.

Pound edited an anthology called, “Des Imagistes,” which can be found online in its entirety. I devoured that, but found myself thinking, “Why is the title French?” and “James Joyce must have been one bored dude to go from this to Finnegan’s Wake (also downstairs).”

But it’s all so interesting, isn’t it? To see how one art form influences another? It amazes me what aspects of haiku have lived on and grown into other (completely different and often contrary) forms. It makes me excited to study it further and apply it to my own writing style in who-knows-what sort of ways.