Rashid Khalidi on settler-colonial Israel: an interview

This interview with Rashid Khalidi, author of The Hundred Years War On Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, was broadcast on Doug Henwood’s Behind the News, October 3, 2024. Khalidi’s family was a member of the old Palestinian elite that was destroyed in 1948 when Israel, freshly born as a state, expelled three-quarters of a million Palestinians from their homes to make way for the settlers. Along with the larger history, he writes extensively about that family in the book. It’s not a new book—though BtN has never been impressed with novelty for novelty’s sake—but it has acquired a new relevance given the latest phase of that century-long war. Khalidi has been an academic for much of his life, but he’s also been deeply involved in Palestinian politics over the years. He’s just retired from teaching at Columbia University, where he now has emeritus status. It’s been lightly edited for publication.

Applying the term “settler colonial” to Israel really annoys its supporters. But not only is it accurate, it’s the language the early Zionists used. Could you review the history of that discourse?

The early Zionist leadership, people like Theodor Herzl, Chaim Weizmann, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, David Ben-Gurion, all believed they had a right to take over Palestine. They believed they had a Biblical right, they believed had a right as people persecuted in Europe in need of a refuge. They represented a national movement, an attempt to develop a national movement out of Judaism and the Jewish people, a modern national movement. At the same time, none of them made any bones about the fact that they were doing this as part of a settler colonial process. The names of the institutions, like the Jewish Colonization Agency, one of the major institutions that was involved in taking over land from Palestinians, indicates that they understood that this was a process of colonization.

The one who was the most open about it was Jabotinsky who said that this is a colonial process. We have a right here. But we understand that this is like any other colonial process and colonized peoples always will resist. Others were less forthright about it, but they all understood the same thing, that whatever their rights were, whatever the justice of their cause in their eyes was, they were doing something that involved displacing an entire people in a colonial process. Nobody ever contested that really before World War II, when suddenly decolonization began, and colonialism had a bad odor globally. And so the Zionist movement and then later Israel began to describe itself as an anticolonial actor because they had come into conflict with the British for a number of years during anf immediately after World War II. But the colonial settler nature of this was confirmed after Israel’s victory in 1947, ’48, ’49, when they expelled three-quarters of a million Palestinians stole their land, refused to allow them to return, took over all of their property. This is settler colonialism. There’s no other description for it really. And anybody with eyes to see who has watched the process of the colonization of the West Bank, the Occupied Territories, Jerusalem, and the occupied Golan Heights since 1967 cannot see anything but settler colonialism. I mean, I cannot imagine how you would describe it unless you’re a Biblical fanatic and say, this is the return of the Jewish people to land to which only they have rights. Well, if you believe that we are not involved in the same discourse,

A striking thing, reading the history is how the Zionist project has relied on imperial patrons, which counters all the David and Goliath metaphors, the settlers just to sell their project. First it was Britain. Now the US. Sometimes one wonders what was in it for the patrons. So let’s talk a bit about the British—why their fervor from Balfour onwards. The British ruling class is a long history of antisemitism. Did they just want to get the Jews out of Europe? What explains the fervor for the project?

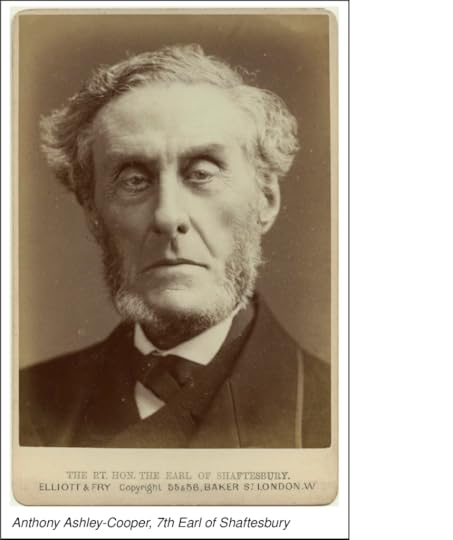

Two things explain the fervor for the project. The first is ideological. It goes back to the early 19th century before modern political science had ever developed, before even the first modern political Zionist writings were committed to paper. And this has to do with a movement in the Anglican Church in England, and among Protestants generally, a great renewal of faith and a rereading of the Bible such that the return of the Jews to the Holy Land was seen as a bounden Christian duty in order to hasten the Second Coming of Christ and so forth. We get the same view among many Evangelicals in the United States today. This starts in the early 19th century, both in the United States and in Britain. The figure most closely associated with it is a very influential British aristocrat by the name of Lord Shaftesbury. He was the father-in-law of the British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston.

He and many others pushed this and this became ingrained in the British Protestantism, this understanding that it was a bounden duty to return the Jews to the holy land. Now, it just happens that at the same time, you have, as you pointed out, a deep strain of antisemitism in England, which goes back to the 12th century when King Edward kicked all the Jews out of England. It was one of many cases where European rulers expelled the entire Jewish population. The King of France did it in the 13th century. The kings of Spain and Portugal did it at the end of the 15th century. And that virulent, theologically based antisemitism was there at the same time as you had this, I guess you’d call it philosemitism or Christian Zionism, among members of the British ruling class. The great irony is that Lord Balfour, who obviously is the person who pens the Balfour Declaration on behalf of the British cabinet in November 1917 in a previous incarnation as conservative Prime Minister, was responsible for one of the most antisemitic acts since King Edward, which was the Alien Exclusion Act to prevent Jewish refugees from the pogroms, the deadly pogroms that were going on in the Russian Empire at the turn of the 20th century, from coming to Britain.

So, you have both of those elements which have to do with philosemitism and Christian Zionism and antisemitism. And secondly, and I think much more important, you have a strategic element. Britain realized early on in the 20th century that it was absolutely vital to its strategic interests, control of the shortest route to India, which meant control of the Suez Canal in Egypt, which meant protecting the eastern frontier of Egypt, which they saw as vulnerable, and which in fact turned out during World War I to be vulnerable, by controlling Palestine and the related realization that there was a possibility of the building of a railway between the Mediterranean and the Gulf, which would become the shortest land route through the Mediterranean, then via railway to the Gulf. And the British decided they had to control that as well. That’s why you have some very peculiar shapes on the map today.

That eastern arm of Jordan, which connects with the western edge of Iraq, is a British concoction to ensure British control of that shortest land route between the Gulf and the Mediterranean. And Palestine is the Mediterranean terminus of that. So for multiple strategic reasons, the British had decided long before Chaim Weizmann, came along, long before Balfour was foreign secretary, that they needed to control Palestine. This was a decision of the Committee of Imperial Defense, of the British General Staff, of British ministers in 1906, ’7, ’8, ’9, ’10, ’11, ’12, long before the Balfour Declaration. So strategic reasons and the idea that the Zionist movement would be a useful pawn in this that enabled Britain after World War I to ignore their promises to other countries to have an international regime in Palestine and to take Palestine for themselves. So, there are strategic reasons and the ideological reasons that I mentioned.

Over time, the Zionists proved very skilled at playing their imperial masters to their advantage.

One of the things you have to understand if you accept that this is a settler colonial project, is that it’s unique. It’s different than any other. Most of the others are extension of the sovereignty in the population of the mother country. Zionism didn’t have a mother country, but it needed an external metropole. And so Herzl ran around Europe to the Kaiser, to the French, to the Ottoman Sultan, to try and find that external patron. Weitzman hit pay dirt in London with the British government. That was something they always understood. That is absolutely vital to keep these external patron or patrons because the project necessitates that anchor in Europe and later on in the United States. That’s something that they used to their advantage when the British decided to limit their promises to the Zionists in 1939, and they pivoted very quickly to the United States and the Soviet Union who became their patrons in the immediate postwar period, pushing through the Partition resolution, which is the birth certificate of the state of Israel, the 1947 General Assembly resolution, partitioning Palestine, both recognizing the state of Israel immediately—it’s established in May 1948—and providing Israel with the arms, which enable it to defeat the four Arab armies that it fought against in the 1948 war.

This attentiveness to external patrons. They later on shift to Britain and France who supply most of their weapons in the fifties and sixties. The weapons that they win the 1956 war and the 1967 war are mainly French and British weapons, and it’s the French who gave them the wherewithal to develop their nuclear weapons. Later on, they pivot to the Americans. So, there’s always been a concern to maintain an anchor in a western European/American metropole for this project, even as it became based in Israel after the establishment of the state.

I don’t want to emphasize the flaws and weaknesses of the Palestinian side too much given the overwhelming power and brutality of Israel and its patrons. But there are some issues to talk about here. One, you write a lot about your family in your book, which was part of a Palestinian elite. You’re critical of that elite. It didn’t seem up to the task, to use the Marxist language, of forming a national bourgeoisie. What were its limitations?

Well, the first thing is it was largely not a bourgeois leadership. The first thing is that it was largely a leadership rooted in the traditional notable class, which were people who were landowners, which were people who were part of the bureaucratic elite of the Ottoman Empire, and who hoped to continue that role under the British and their brethren and sistern, or mainly brethren, in other Arab countries did that. They were not a bourgeoisie. The bourgeoisie was a junior partner in that leadership of the 1920s and 1930s. They were not particularly democratic. They were not engaged in mass politics for the most part. They were traditional leadership of what Albert Hourani called notables, the kind of people who had been part of Ottoman governance for generations and generations, centuries actually. And they hoped and assumed that they could continue to play that role under the British

They were sorely mistaken because they fundamentally misunderstood what the British were doing. The British intended to replace them and their people with an entirely different leadership and an entirely different people. That’s what the Balfour Declaration said. That’s what the mandate for Palestine said. And one of the great failures of this leadership was to realize this early enough. Eventually, Palestinians realized this and rose up in revolt, but it wasn’t a revolt that was organized by or led by this traditional leadership. It was a grassroots, popular uprising that led to a three year rebellion that the British only put down with great difficulty. And the leadership doesn’t come off well in my reading and in the reading of I think most historians during this period from World War I to 1948.

And you also write about how over the decades the leadership of the PLO has been ill-prepared, no match for the Israeli counterparts, no political strategy to influence outside opinion. The leadership enjoyed its perks and forgot their constituents. Now, we shouldn’t overlook how many of the most dynamic leaders Israel assassinated—even in the cultural sphere—but the leadership has been fairly unimpressive. Why?

A couple of things. I’m very critical of them. But they achieved certain things. You have to give them credit for resuscitating the Palestinian national movement in the fifties and sixties at a time when everybody thought that Palestine had disappeared from the map. The Israelis were gloating. I believe it was Golda Meir who said, the old will die and the young will forget. Well, the old died, but the young did not forget, and it was this leadership that revived the Palestinian national movement, to their credit. It had been completely destroyed, shattered. The previous leadership was discredited. They were all scattered to the winds. That class and those individuals and those families that had dominated Palestinian politics up to 1948 disappeared from the political map. And the new ones, to their credit, resuscitate the Palestinian national movement and get the Palestinians a seat at the table.

Now, what they did with that seat is where the burden of my criticism comes in, which is that they utterly failed to understand the global balance of power, to understand the United States and Western Europe, to understand how those places functioned and how hard it would be to overcome the visceral nature of Western support for the Zionist project and for Israel. I think a comparison with the Zionist movement and Israeli leaders is quite useful here. You’re talking in the case of people like Herzl, Ben-Gurion, Weitzman, people like later on, Abba Eban, Golda Meir, Benjamin Netanyahu, of people who are Americans, Europeans in their origins, in their education, in their outlook, in their training, in their language, and their culture, and are also Israelis, or Zionists for the ones who like Herzl who die long before the state is created Jabotinsky. All of these are people who are at home in the European milieu.

They understand Europe and the United States. Golda Meir lived in Milwaukee for years. Netanyahu lived in Philadelphia and at Cornell where his dad was teaching for years. You listen to them, you listen to Golda Meir, you listen to Benjamin Netanyahu, and you hearing the accents of natives from this country. And that’s true of Abba Eban and speaking perfect Oxford English. He was South African by origin. So, you’re talking about an elite in the Zionist movement and later in Israel, a large proportion of whom profoundly understand Western culture and politics because they were part of it. That’s not the case for the Palestinians. Until the present generation you do not have people who’ve grown up and have been steeped in Western politics, Western culture, Western languages, Western law, and they therefore were in an enormous disadvantage by comparison with Zionists and later Israeli leaders in dealing with the West, whether strategically or in terms of public relations or diplomatically or in any other way. And that has shown unfortunately in the performance of the PLO, well, the Palestinian leadership of the twenties and the thirties, but the performance of the PLO and more recently of the Palestinian Authority. They’re pathetically out of their depth in dealing with the United States and Western countries. The PLO did a pretty good job dealing with the Third World. They were relatively successful. They could understand that Global South because they were part of it. They could relate to it, they could speak to it. They did not have the same facility with the United States and Western Europe.

I can understand the Cold War logic of an alliance with Israel as a bulwark against Communism. The USSR has been dead for over 30 years. Most Arab regimes are now very reliable US allies. So how do you explain the lingering support for Israel and its absolutely manic intensity?

Well, there’s multiple elements. I mean, you have the Evangelical element, which is a throughline from Britain in the 1930s and 40s through the United States in the 2020s. That is a base of support that is solid in every era, given that it’s theologically grounded. Second thing that you have that’s important is that all of the leading institutions of the Jewish community have been won over to Zionism between the 1940s and the 1960s. Most Jewish communities in most parts of the world were not particularly favorable to Zionism until Hitler comes to power in the thirties and until the Holocaust. That’s true in the United States. It’s true in Europe. People voted with their feet. Thousands went to Palestine, [laughs] millions went to the United States and Canada and Australia. Or they stayed and tried to change their societies or keep their heads down. They were not convinced of the tenets of Zionism until European antisemitism reached this mad paroxysm of the Holocaust.

And that understandably changed a lot of people’s minds. And by the 1960s, the American Jewish Establishment, the leading institutions of the American Jewish community, had come to treat Israel as a central element in Jewish identity as they came to treat the Holocaust as a central element of self-understanding. And the two were seen as linked, of course. So that’s another element. It’s increasingly unrepresentive of younger generations of people in the Jewish community, but it’s certainly true of the people in the sixties and seventies who own most of the money and controlled most of the institutions. The conference of Presidents and the ADL and the American Jewish Committee and so forth are run by people whose political consciousness was formed in the fifties, sixties, and seventies. And that was an era in which an Israeli narrative took root in that community.

And then finally, you have strategic elements. You’re absolutely right that Israel was a particularly valuable ally during the Cold War. It was seen as the trump proxy against Soviet proxies. But you’re also right that the Cold War ended in 1991 with the demise of the Soviet Union and that the United States has continued to see Israel as a valuable ally because the United States has found other bogeymen to justify its strategic stranglehold over the Middle East—the Islamic Revolution in Iran and the regime that grew out of that, and then later on, various terrorist outfits like al-Qaeda and ISIS. And Israel successfully sold itself at the turn of the 21st century to the United States as an indispensable ally in the global war on terror. And we see this today in the seamless cooperation between the American intelligence services and the American military with Israel in hunting down Hamas leaders in Gaza and in hunting down Hezbollah leaders in Lebanon.

There’s reportage in the New York Times, which is the main propaganda outlet for Israel in the United States, this is taking place, and this goes back to this idea that these things are joined at the hip. Everything that the United States finds objectionable in the Middle East, including global terrorist outfits like al-Qaeda and ISIS are no different than Hamas and Hezbollah, which of course have national roots and national causes, and are rooted in the Palestine issue and in Israel’s occupation of Lebanon, and not in some global Islamism. But there’s a narrative that Israel succeeded in selling in this country—Netanyahu played a crucial role in this, but it was Ariel Sharon who was really the most successful salesman at the outset—such that the United States has hitched itself essentially to Israel’s war on a variety of actors in the Middle East, with the complete illusion that these are America’s enemies just as their Israel’s enemies. It’s hard to see exactly how Hamas is the United States’s enemy, except that it’s linked to Iran and this hostility between the United States and Iran. this enmity, goes back to the Iranian revolution.

You wrote in The Hundred Years War, which was published in 2020, so I guess you wrote these words in 2018 or ‘19, about how American public opinion was changing, and we’ve certainly seen that accelerate over the last year. How wobbly is the Zionist discursive hegemony these days in the US?

Well, it depends on who you talk about. If you talk about public opinion in general, that hegemony has disappeared. It’s fighting a rearguard action, and because its narrative is so threadbare, it’s obliged to resort to completely spurious allegations of antisemitism to smear people who are calling for Palestinian freedom or people who are decrying the slaughter of civilians in Gaza now in Lebanon. On that level, it’s fighting a rearguard action. On the elite level, however, on the level of the mainstream corporate media, on the level of the great institutions of our society, the universities, the museums, the foundations, on the level of our politics, it’s still hegemonic. There’s not a politician who doesn’t repeat some drivel that’s drawn from this Israeli playbook every time they open their mouth. “The only democracy in the Middle East”—a country that’s kept a population almost as large as the Jewish population of Israel under prison camp conditions and military occupation since 1957 is the “only democracy in the Middle East”?

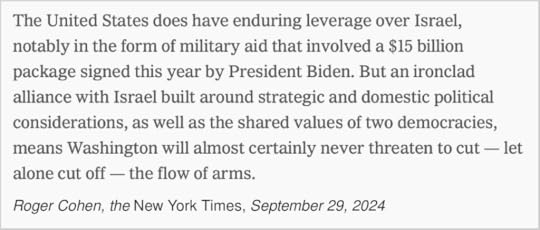

Millions of Palestinians have lived under the jackboot of a military government locked up in Gaza or held in cantonments all over the West Bank by Israeli walls and Israeli checkpoints without any right to determine anything about their lives, whether they can go, they can come, they can import, they can export, that they can’t register their children in the without Israeli permission. That’s a democracy? There isn’t a politician who doesn’t repeat that nauseating lie. Roger Cohen, today’s New York Times, shared democratic values. So let me see. Torture in prison camps is a democratic value. Slaughtering civilians at a ratio of three to one or four to one, as against your nominal enemies, is it in a democratic value? That bilge is repeated ad nauseum by all of the elites, whether the political or the media or the corporate or the other elites. So, on one level, that narrative is still hegemonic, and that’s unfortunately the level of the people who own and control our politics and our economy and much of our cultural production. At a grassroots level among artists, among students, among unions, among churches, and among minorities, that narrative is in deep, deep trouble.

Is there a way out of where we are, one secular democratic state sounds appealing but impossible to imagine. The old two state solution with the Palestinian one fully sovereign and not an apartheid style bantustan—that seems almost as dreamy, more dreamy than ever after this latest round of bloodletting. And given the destruction of the civilizational infrastructure, the Palestinians, and the hardening of Israeli attitudes, can you imagine any kind of plausible solution at this point?

Well, I don’t think anything is possible in the immediate future, given what you just said. Israel suffered a series of traumatic shocks on October 7th. It was the first invasion of Israeli territory since 1948. It was the largest civilian death toll in Israel since 1948. It was the most severe defeat of Israel’s military, certainly since 1973, and 800 civilians were slaughtered. It was a massive intelligence failure. The traumatic shock of all of that is still reverberating in Israel and has very much hardened Israeli attitudes. The slaughter of 42,000 people in Gaza, as you can imagine, has hardened Palestinian attitudes and the ongoing slaughter of, whatever the toll is, 1,200 people, most of whom as always with the Israelis are civilians, is going to harden attitudes in Lebanon and other parts of the Middle East.

So, nothing can be envisaged in the short term. In the medium and long term, you’re going to see decreasing support for Israel in the West. This ludicrous idea of shared values is going to be tattered. Now, Western values may change. The West may become more autocratic, more undemocratic, more hostile to the rest of the world. That’s certainly possible. The rhetoric of a Trump or the rhetoric of an Orban or the rhetoric of the Austrian party that just won the election indicates that that’s a possibility. In which case, Israel is a perfect ally. Tramples all over international humanitarian law, spits at the United Nations, is hostile and racist towards non-Jews. That’s an attitude that I think a lot of major political parties, including the Republican Party, would find perfectly congenial. But unless that is the future of Western European countries and the United States, there’s going to be a separation of ways between this absolutely essential metropole and this project in Israel.

And there’s going to be a problem within Israel because a lot of people are going to say, is this the country I want to bring my children up to live in? There’s a flight of people from the Middle East. There’s a flight of Israelis from Israel. There’s a flight of Palestinians and Lebanese as well. A hundred thousand Lebanese left for Syria in the last 24, 48 hours. Imagine going to Syria, a war-torn country because you’re in such danger in Lebanon. But Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan, Egypt, Syria, those countries are going to endure. Israel is going to have a problem because the kind of people who are leaving are the doctors from the hospitals, the high-tech folks, the investors, the professors, the more liberal element of Israeli society, and also the more educated and more productive members of Israeli society. And this is going to be a problem going forward. Do you really want your children to be occupying South Lebanon in 2030? Do you really want your children to be occupying Gaza in 2028? Well, that’s the future that this regime, this government in Israel is plotting for that country. I don’t think that that’s a future a number of Israelis at least, are going to enjoy living with.

Video of Rashid Khalidi’s conversation with Carrington Morris, a September 22 event organized by New York City DSA’s political education committee, is available here.

Doug Henwood's Blog

- Doug Henwood's profile

- 30 followers