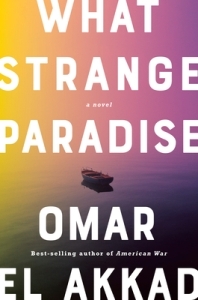

What Strange Paradise, by Omar El Akkad

This Giller-prize-winning, Canada-Reads-nominated 2021 novel opens with an image that still haunts many of us in memory: a small boy lying facedown on a beach in Turkey, dead after the sinking of a migrant boat that was trying to reach the Greek island of Kos. This is not a novel about two-year-old Alan Kurdi, whose death in 2015 was captured in images shared around the globe. But in another way, it is — because it is about all migrants, especially migrant children, and about this moment in history where we find ourselves.

The boy on the beach in What Strange Paradise is nine-year-old Amir Utu, whose family fled the war in Syria for Egypt. Amir follows his uncle onto a crowded boat that, though Amir doesn’t know it, is headed for a Greek island in hopes of finding a safe haven and a stepping stone to Europe. Unlike Alan Kurdi, Amir survives — but doesn’t find safety. On the island, a tourist-driven economy is being disrupted by the waves of refugees landing on their shores — and empathy is in short supply. When Amir meets a local teenager, Vanna, the two try to evade the soldiers who want to make sure all migrant arrivals are captured, processed, and detained in a camp.

The novel’s timeline moves back and forth between Amir and Vanna on the island, and the backstory of the voyage that led Amir there. Although the reader empathizes with Amir and wants him to find safety, this is not a simple story of black and white, good and evil (though there is plenty of evil at play). Rather, it is a novel about the complex web of motivations that lead people to become refugees, to exploit refugees, to control refugees — everyone in this story has mixed motives, except perhaps Amir himself.

The book ends with a memorable twist that is open to many different interpretations, and might change your perspective on what you’ve read in the preceding chapters. However you interpret it, this remains a heartbreaking story of the lengths people will go to to find safety, and how slim the chances are that they will actually find it.

The migrant crisis hasn’t been in headlines like it was in 2015 when Alan Kurdi died on that beach, but it hasn’t gone away, and as attitudes towards “the other” harden in many wealthy countries, decisions about how we deal with the mass movement of desperate people in search of new homes become more urgent than ever. This novel is a powerful voice to add to that conversation.