Beatrix Potter: Author and Naturalist, Part III (Conclusion)

To enjoy the complete story of Beatrix Potter’s early fascination with the sciences, read Part I and Part II!

What does it take to create a storyteller? I am sure that some of us would be able to spin a fine yarn without ever leaving their homes or venturing into other realms of art and science.

However, the advice ‘write what you know’ rings true in most situations. A story might fall flat if the author is trying to write something they do not know, or if they try explaining something they have not researched.

Beatrix Potter’s quest to learn about fungi is one example of this. In her case, she was not only writing what she knew; she was drawing it, as well. At the age of fifteen, she became frustrated by the lack of information about fungi in the forests surrounding her family’s estates. Even in the expensive nature books, it was a topic not often covered.

Her studies began in childhood, continuing when she became a young lady. She conducted them independently, unable to consult experts due to restrictions imposed on women at the time.

One of the main hubs for the natural sciences, Kew Gardens, was off-limits to anyone without a ticket (not just women). In order to obtain a ticket, a person needed a recommendation from someone whose name bore weight. In Beatrix’s case, her uncle Henry was the surest source of obtaining a ticket.

After years of pestering, Uncle Henry finally agreed to help obtain the ticket when she was 33.1 (Read the footnote—it’s important, regarding my first two posts.)

My previous post ended with Beatrix and Uncle Henry visiting Kew at last. Before consulting the director, he introduced his niece to several professors. Among them was a botanist named George Massee, who had been the first president of the British Mycological Society.

Massee was now second in command at the Herbarium she was so desperate for access to. He was known as a bit of a romantic; perhaps that’s why he would later be open to conversation with Beatrix. He examined her botanical drawings, though she does not report whether he commented on them negatively or with enthusiasm. He must’ve had some confidence in her work, for his later collaboration would prove to be of great help to her.

After their promising meeting with Massee, Beatrix and her uncle visited the director’s office in search of that elusive student ticket. This ticket would allow her unlimited access the gardens and Herbarium. It would unlock possibilities that had been unthinkable to her previously.

Beatrix later wrote that Director Thistleton-Dyer paid greater attention to Uncle Harry. I imagine that the professor was amused by her portfolio, perceiving her as an overly curious young lady who liked to draw.

We can hardly blame him for this infuriating mindset. After all, ladies at the time were not encouraged to pursue science; ladies were taught to be quiet and marry.

At the end of this exchange, Beatrix Potter was granted her student ticket. However, she wrote in her journal about being patronized throughout the interview. Later, she was ignored completely, as if the director had forgotten she was there.

Well, one might think, at least she was victorious in acquiring her ticket. This is true, but I cannot help but think about how I would feel in her position. It must have been bittersweet, indeed; I became frustrated simply reading about it.

Beatrix would return to Kew Gardens often in the years that followed. She became a frequent face, especially after she was commissioned to make lithographs of insects for a museum. Kew had the fossils and specimen that she needed in order to add detail to her graphs.

***

Though it appears that she cannot escape the title of childrens’ author, Beatrix Potter was much more than that. Her letters and journal entries demonstrate that she was sharp-tongued and iron-willed. It is this attitude that carried her through the many challenges that life presented to her, including heartbreak, loss, and war.

Beatrix Potter was underestimated by everybody, even her family. Her mother and father tried to prevent her from doing things she was passionate about, even when faced with her success. As she grew older, her writing and illustration brought some financial independence. This enabled her able to continue following her dreams, surprising the world—and, perhaps, herself as well.

The “fungi fixation” is one of many details that gripped me as I read the book Beatrix Potter: A Life in Nature by Linda Lear. It is brilliant book, detailed in recounting the most significant moments of Beatrix’s life. I wrote these posts because I thought more people should know about her impressive childhood hobby. It would not remain simply a hobby; later in life, she would become a champion of wildlife conservation, purchasing land to save the flora of the countryside that she had loved and studied.

Having told my readers about this chapter of her life, I say to Beatrix, “Farewell, for now.” (Mary Shelley and Clara Schumann are demanding my attention next, and I find I can’t say no to either of them).

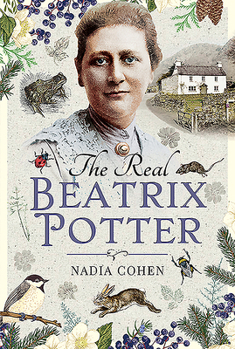

In a few weeks, I will begin The Real Beatrix Potter by Nadia Cohen, seeking more of her story. I wish to understand her life from a different perspective as I plan my longer essay. The ultimate goal is to help readers appreciate that Beatrix achieved things aside from The Tale of Peter Rabbit.

She was an author, of course, but she was also a resourceful and clever businesswoman, in control of her stories and subsequent merchandise. We admire modern figures for protecting the rights to their work. Beatrix Potter could almost be called the original. She was in charge of her career (at least, as much as she could have at the time, when laws where so different and pitted against women).

I’m eager to present this essay, polished and informative. Once finished, it will be published on Substack behind a paywall. In the meanwhile, I hope you enjoyed these three free posts. I also hope you’re impressed by the great lengths Beatrix Potter went to in the name of education.

Thank goodness young ladies do not need to jump through so many hoops now in order to learn.

Note: I must admit to accidentally publishing misinformation in my first two posts. When I began writing, I believed Beatrix was fifteen when she first stepped into Kew Gardens. Such a misunderstanding took place because the book Beatrix Potter: A Life in Nature is dense, each page rich with detail. This is my first work of nonfiction in three years; researching/notetaking is something I will improve at in time. The moral of the story is be careful with speed-reading!

The fact that Beatrix was ignored as a 33-year-old woman somehow makes the insult worse. I could understand a director thinking a fifteen-year-old’s investigation not worth his time, but at that point, Beatrix was not a child.