Brain of Albert Einstein.

Friends,

Sometimes, I come across information that makes me stop in my tracks. Information that I had some small tidbit of knowledge of, but not the whole story.

Such as it should be when there is so much to learn.

I had a friend when I was going through my Master’s program who was studying to be a medical historian. Honestly, at that time, I didn’t know that history could be spliced into certain subjects within the subject: history of Medicine, history of Scientists, history of dental procedures or medical practices.

Usually, with these smaller sub-subjects, the historian will narrow it down even further to a certain time or, in this case… person.

Albert Einstein is a favorite among historians studying science or space. Or how a genius brain works.

Back StoryNow, Einstein had a brilliant life, and I could spend weeks talking about his childhood, early life, scientific contributions, and final years…

What I want to talk about is what happened to him after he died.

Einstein passed away on April 18, 1955, at the age of 76, of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. He was a pipe smoker and was often found picking up stray cigarette butts along the Princeton University campus and using the discarded tobacco to fill his pipe. At the time, he insisted that smoking ‘contributes to a somewhat calm and objective judgment in all human affairs.’

As a lifelong smoker who has recently quit smoking cigarettes- I will be the first to admit that I don’t think he is wrong.

As long as you ignore the medical concerns and potential death.

Side note- it was thought he died of syphilis due to his MANY affairs, but the autopsy proved that while he was very free with his love- he never contracted the deadly disease.

The autopsy.Thomas Harvey was the pathologist on call the night Einstein died, and by all accounts, it was like winning the lottery. For years, people had wondered if the brain was formed differently for people of higher IQs or with specific medical/mental health diagnoses.

And here was the body of arguably the most intelligent man in the world. Havey couldn’t wait to open him up.

The problem was that Einstein had already left specific instructions that he wanted to be cremated and his ashes scattered secretly to discourage idolaters.

Did Harvey get permission? Nope. He took it upon himself to perform the autopsy because what would Einstein do? He was already dead.

Better to ask for forgivenessWhat did Einstein’s children have to say when they arrived at the hospital for their father’s body? Well, they were none too pleased. But the damage had been done, and Harvey talked a sweet game. Hans Albert, Einstein’s son, gave his permission somewhat reluctantly to have his father’s brain studied, and any results would be published only in reputable scientific journals.

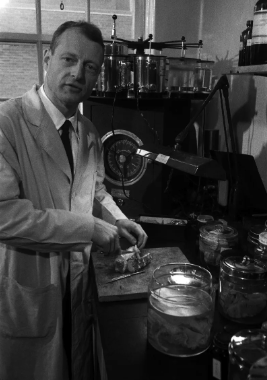

Not all is forgivable. Harvey, on the day Einstein died. (Image credit: Getty)

Harvey, on the day Einstein died. (Image credit: Getty)Within months, Harvey was dismissed from Princeton Hospital for refusing to give up the brain. Interestingly, he had also taken Eienstein’s eyes, which he had sent to Einsein’s eye doctor, Henry Abrams. (They are currently in a lock box in New York City. There are rumors on the auction block circuit that they are periodically up for sale, but so far, they have never been advertised.)

Now, here is where the story gets stranger. Harvey was not a brain specialist.

He was a pathologist, a medical doctor specializing in analyzing tissue, blood, urine, and other body fluids to diagnose and treat medical conditions, not someone who studies how the brain works.

Road TripAfter Harvey lost his job, he took Einstein’s brain on the road. The first stop was a Philadelphia hospital where a technician sliced the organ into over 200 blocks and embedded the pieces in celloidin. The remainder of the brain was settled into formalin-filled jars and stored in the basement of Harvey’s home in Princeton.

When Harvey’s marriage failed, his ex-wife threatened to throw the jars away, and Harvey headed to the Midwest, Einstein in tow.

For a while, Harvey worked as a medical supervisor in a biological testing lab in Wichita, Kansas, and kept the brain in a cider box stashed under a beer cooler.

Havey left that job and moved to Weston, Missouri, where he practiced medicine while studying the brain in his spare time. He lost his job in 1988 when he failed a three-day competency exam and headed to Lawrence, Kansas, where he took a job as an assembly-line worker in a plastic factory.

This is when Harvey thought it would be an excellent time to ensure his name wasn’t forgotten. He would cut chunks of it off and send them to researchers worldwide. Ironically, he didn’t have many scientists beating down his door for a chance to own a piece of Einstein.

Most of the purchases were made by people who just really liked Einstein.

The journey wasn’t over.In 1997, Harvey embarked on a cross-country road trip with a reporter named Michael Paternniti to find Einstein’s granddaughter. With the brain safely tucked into the trunk of a Buick Skylark, the two men set off on an adventure from New Jersey to California.

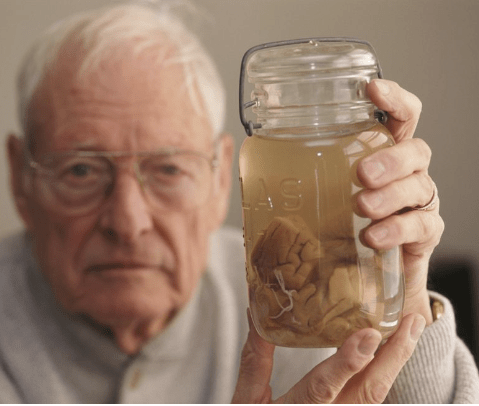

Thomas Stoltz Harvey holds up a jar containing a piece of Albert Einstein’s brain in 1994. Harvey oversaw Einstein’s autopsy in 1955 and kept much of the physicist’s brain in his possession for more than 40 years. (Image credit: Getty)

Thomas Stoltz Harvey holds up a jar containing a piece of Albert Einstein’s brain in 1994. Harvey oversaw Einstein’s autopsy in 1955 and kept much of the physicist’s brain in his possession for more than 40 years. (Image credit: Getty)By all accounts, Harvey had a change of heart and decided to hand the jars over to the granddaughter. But she didn’t want them. Where would she put a jar full of brains? On the mantel?

So it was back to Princeton they went.

In 2010, Havey’s heirs transferred the remains to the National Museum of Health and Medicine to include 14 photos of the brain before the sectioning. Something the medical community had never seen before. If you ask me, the photographs got more attention than the actual brain.

In 2013, the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia acquired 46 small portions mounted on microscope slides, and now on permanent display.

I have been to the museum on a family vacation, and I can say with all certainty that it’s not much to look at—just rows of what looks like kidney beans. (Sorry, Einstein.)

But the plaque was really nice.

His was not the only one.The concept of studying the brains of famous people is not a new phenomenon. Carl Friedrich Gauss, a famous German mathematician, had his thinker preserved 100 years before Einstein.

Vladimir Lenin’s brain is currently hanging out at The Department of Brain Research of the Scientific Center of Neurology of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences. His body is buried in a mausoleum on the Red Square.

Ishi, the last known Yahi (a Native American tribe Indigenous to Northern California), was first a living exhibit at the Pheobe Hearst Museum of Anthropology at UC Berkeley until his death of tuberculosis in 1916. His body was cremated, but his friend, anthropologist Alfred Kroeber, sent his brain to the Smithsonian. It wasn’t until 1999 that the Smithsonian decided to give the remains back to be reunited with his remains in Tehama County.

John Edward Howard Rulloff, a Canadian-born American who was a doctor, lawyer, schoolmaster, photographer, inventor, phrenologist, and philologist, as well as a serial killer, has his brain currently on display at the Wilder Brain Collection at Cornell University.

Final thoughts.As a historian, I am often thrilled when we find the body of our ancestors. It can share so much valuable information on culture, way of life, beliefs, religions, and diet.

It can also put a name to the dead.

But then there are cases like this one that don’t just border the line of mistreatment but jump into the abyss of ‘you got to be shitting me.’

When you think genius, the first name that pops up is Albert Einstein. He will always be an international hero. His life will be studied for generations to come. When we can no longer extract information from his diaries, papers, and brain, someone will find something to write about.

His name will always be remembered.

But this is a case of respecting the person vs. respecting their death. A line was crossed. We praised Einstein for what he gave us as a society and then disrespected him as a person. I will never think this was ethical, moral, or even something that should have been done in the name of science.

RIP Albert Einstein.

Until next time, Keep Reading and Stay Caffeinated.

If you’re looking for your next favorite read, I invite you to check out my book, The Raven Society. This spellbinding historical fantasy series takes us on a heart-pounding journey through forgotten legends and distorted history. Uncover the chilling secrets of mythology and confront the horrifying truths that transformed myths into monstrous realities. How far will you go to learn the truth?

The Writer and The Librarian (Book 1):

Signed copies at:

https://rlgeerrobbins.com/product/the-writer-and-the-librarian-the-raven-society-book-1/

The Under Covers Bookstore (UK):

The Writer and the Librarian | The Under Covers (theundercoversbookstoreandcafe.com)

The post Brain of Albert Einstein. appeared first on R.L. Geer-Robbins / Author.