Judging Race in “Judgment Day!”

As folks who have visited my blog before probably know, I’ve been working on my book-in-progress The Color of Paper for a while now. I’m nearing a book contract, but I got some recent feedback that revealed that my introduction wasn’t doing the basic job of an introduction: introducing unfamiliar readers to the book

So I’m now beginning with an example that I hope encapsulates what the rest of the book explores in detail: how a material image composed of ink on paper conveys the culturally constructed concept of a racial category. I think the example is also one of the more prominent single-image racial representations in the history of the comics medium.

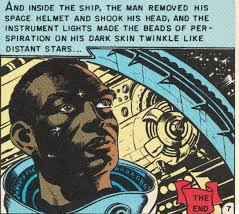

Qiana Whitted opens her Eisner-award-winning EC Comics: Race, Shock, and Social Protest with a discussion of scripter Al Feldstein and artist Joe Orlando’s science fiction comic “Judgment Day!” in Weird Fantasy #18 (March 1953). “When the space investigator removes his helmet in the final panel,” writes Whitted, “viewers see for the first time that [he] is a black man” (4). Whitted later describes Orlando’s framing, how the astronaut’s face is “positioned generously in the foreground against the ship’s machinery so that there is no mistaking him” (116), meaning no mistaking that he is “a man of color” (117). According to Orlando, his drawing is an especially effective rendering of “a black guy,” superior to any by fellow EC (Entertaining Comics) artist Wally Wood (116). Whitted agrees, noting generally that Orlando’s “line work was known for its precision and craftsmanship” (115) and specifically that this drawing “accurately reflects the features of a man of African descent in the texture of his hair, the physical rendering of his lips and nose, his deeply set eyes, and his cheekbones” (116).

Colorist Marie Severin assigns a medium brown to the area of the image representing the astronaut’s skin, contrasting the surrounding yellow and blues of the space suit and ship interior. Severin’s skin color choice also contrasts the inhuman gray-brown used by other comics publishers of the period, including Marvel’s predecessors Timely and Atlas, to denote Black skin. In 20th-century comics printing, the astronaut’s brown skin was produced by a combination of blue, magenta, and yellow percentage-sized dots on the off-white surface of pulp paper. Though the brown is printed uniformly and so unrealistically, combined with Orlando’s use of opaque black for hair and shaded facial areas, the effect is overall realistic. Whitted also suggests that the astronaut’s “dark skin becomes an expression of space itself” (128), though that effect is conveyed more textually than visually through narration printed in the final caption box: “the instrument lights made the beads of sweat perspiration on his dark skin twinkle like distant stars.”

According to Feldstein’s account, the head censor for the recently formed Comics Code Authority immediately recognized the image as representing a “Negro” (Hadju 322). Was it Orlando’s rendering, Severin’s color selection, the “dark skin” of Feldstein’s text, or some combination of the three?

Beginning in 1954, the Comics Code prohibited a range of offenses including the “ridicule” of any “racial group,” as was previously common in the medium’s drawing norms. Stanford W. Carpenter describes the astronaut’s “low angle head shot” as “quite handsome” and therefore not “caricatured according to traditional codes of cartooning and comics art” (29, 30, 20). Whitted terms Orlando’s style “an aesthetics of accuracy” (118), which means the astronaut’s Black racial identity is not conveyed through what Rebecca Wanzo calls “the phantasmagoric nature of stereotype” which contains “no relationship to real phenotype” (1). Orlando does not reproduce aspects of the minstrel tradition that dominated the visual representation of Black people in U.S. from the early 1800s to the mid-1900s. Had Orlando, for example, exaggerated the astronaut’s lips or nostrils to impossible proportions, viewers familiar with those racist visual tropes might recognize them as symbolizing Blackness. Viewers instead observe Orlando’s drawn image as though observing an actual individual, forming conclusions about the depicted figure’s race as they might form conclusions about any observed individual’s race.

Since the fictional astronaut is from Earth’s distant future and so outside contemporary U.S. race norms, those conclusions are based only on his physical features, the “real phenotype” Wanzo references above. In “Black Looking and Looking Black: African American Cartoon Aesthetics,” Joanna Davis-McElligatt uses “Black phenotype” to reference an artist’s rendering of a comics character’s “Black curly hair, dark eyes, rich brown skin, and wide nose and lips” (199). She places such “portrayals of Black phenotype” as distinct from both “Black expressive culture” and “the conventions of Black being,” as well as distinguishing “Black phenotype, or looking Black” from “Black behavior, or acting Black” (195, 206). The ending impact of “Judgment Day!” requires viewers not to have understood the astronaut as “acting Black,” and so not expressing Black culture or conventions, prior to the last panel where his racial identity is conveyed only through an appearance of “looking Black.”

Based on Orlando’s self-assessment, which Whitted confirms, his original black-and-white image suggests a Black phenotype prior to and so independently of Severin’s color additions. If so, viewers of Judgment Day and Other Stories, the 2014 black-and-white reprint edition of Orlando’s EC works, would still recognize the astronaut’s intended race. The same might not be true of other EC reprints. Whitted agrees with Orlando’s assessment of Wally Wood’s drawing of what appears to be “a white person with dark color,” meaning “racially indeterminate images of African Americans” (116). In such cases, the addition of brown would be racially determining, making color the defining element of phenotype-based racial judgments. Since blocks of colors are applied to paper without gradations or other naturalistic qualities, such as variations between members of the same racial group, color may denote a character’s race while paradoxically revealing little about that character’s diegetic skin color. Wanzo notes an extreme example in which a child with skin rendered entirely in black ink represents a historical figure known to have very light skin (1). Despite the crudeness of the period’s color printing, Severin’s brown when combined with Orlando’s naturalistic rendering might still create the impression of viewing the character’s skin color directly and so not communicate the astronaut’s race symbolically.

Removing Severin’s colors also removes, or at least reduces, the astronaut’s beads of perspiration, since the most noticeable beads are small areas of the off-white paper made legible through contrast. In Orlando’s black-and-white art, the interior of the beads and the astronaut’s visible skin are both represented by the color of the paper, which has the paradoxical ability to represent any color. That page whiteness does not, however, express the blackness of space, which is represented by Orlando’s opaque black ink. In Severin’s color version, only the interior spaces of the beads and the stars are the color of the paper, reinforcing the narrator’s verbal comparison. Even here though, the verbal differs from the visual, since the astronaut’s face is comprised of black and brown with beads of page whiteness, and outer space is comprised only of black and stars of page whiteness. To describe a Black figure’s skin as akin to black outer space is to understand “Black” as the literal color that the racial metaphor uses to produce a false logic of absolute oppositional difference, literally black and white. Whatever his race, the astronaut’s skin is brown.

The page areas surrounding the rectangular panels in “Judgment Day!” are also uncolored, allowing page whiteness to structure the relationship between images by representing a nothingness that is conceptually distinct from the physical page that each copy of the comic is printed on. The perspective of the final panel also establishes a point-of-view that appears to extend beyond the surface of the page and therefore as if into the bodily space of any viewer holding the comic. If a viewer is white like the Comics Code censor who objected to the astronaut being a “Negro,” then the ending revelation may also reveal that the image’s racially unspecified implied viewer, like the astronaut, is not necessarily white either.

Whitted’s analysis of “Judgment Day!” also provides a visual coda. The cover of her 2019 study features an illustration by Afro-futurist artist Marcus Kiser: an astronaut with a raised helmet visor framed and centered by white gutters. Like Orlando’s image which Kiser’s evokes, this astronaut appears to be Black. Unlike Severin, Kiser uses non-naturalistic hues: the astronaut’s skin and suit are the same blue, and the black of outer space behind him is yellow-orange. By destabilizing color as a racial marker, only the black ink delineating facial features can suggest race. Though non-exaggerated and so nothing like Wanzo’s phantasmagoric stereotypes, Kiser’s rendering of lips and nostrils are larger than Orlando’s, and Kiser’s lines are gestural rather than precise. Orlando’s astronaut also stares off at the distance beyond the top right panel corner, while Kiser’s stares directly forward, merging the image’s point of perspective with the position of an actual viewer.

Chris Gavaler's Blog

- Chris Gavaler's profile

- 3 followers