Two Tales Illustrating How, Even as a Minor Character, Baba Yaga Is Unpredictable

English translations of Russian Baba Yaga folktales suggest that oral storytellers adapted the character — who probably would’ve been familiar to their fireside listeners — to the needs of the tale being told. Sometimes, she’s a witchy major character, the narrative’s antagonist. Other times, she’s a minor character, but her villainous nature still frustrates the protagonist’s efforts to achieve some goal. Occasionally, she acts as a minor character, but she generously gives trustworthy guidance to the hero (along with a good meal and a night’s sleep). If you’re ever journeying through the woods and come upon Baba Yaga’s hut, beware — she’s unpredictable.

The range of Baba Yaga’s fickle disposition is well illustrated by “The Frog-Tsarevna” and “The Footless and Blind Champions.” She appears only briefly in both of these. Let’s start with her in a good mood.

The Frog-Tsarevna; Or, Baba Yaga Ain’t So Bad — SometimesI was reminded of the Celtic legend of the selkie when reading “The Frog-Tsarevna” (a.k.a. “The Frog Princess” and “The Frog Queen”), since the title character can remove the skin of her amphibious self to become a woman. Of course, she’s a frog-woman, not a seal-woman, but true to selkie lore, her husband restricts her freedom by stealing her skin. He even burns it!

How Ivan came to marry Vasilisa Premudraya, the woman who’s perfect except for the frog thing, comprises the tale’s first act. Act II introduces his destroying her skin, and that’s when Vasilisa informs Ivan he should’ve been more accepting. Following R. Nisbet Bain’s 1895 translation, Vasilisa laments:

"Alas! Tsarevich Ivan! what hast thou done? If thou hadst but waited for a little, I should have been thine for ever more, but now farewell! Seek for me beyond lands thrice-nine, in the Empire of Thrice-ten, at the house of Koshchei Bezsmertny." Then she turned into a white swan and flew out of the window.Ivan! You royal idiot! To be sure, he recognizes that he’s been too controlling and humbly begins a quest to win back his bride. Along the way, Ivan meets Baba Yaga.

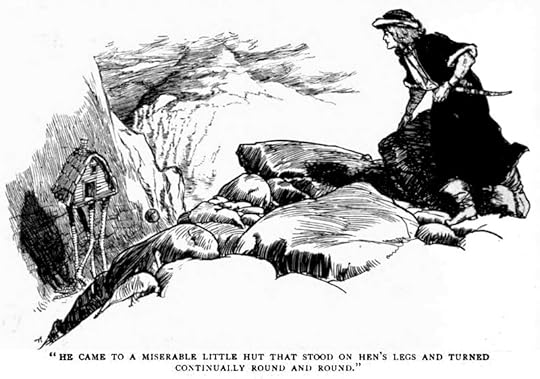

H.R. Millar’s illustration for Post Wheeler’s translation of the tale, published in a 1912 issue of The Strand magazine.

H.R. Millar’s illustration for Post Wheeler’s translation of the tale, published in a 1912 issue of The Strand magazine.We’re sure it’s Baba Yaga thanks to her quirky hut that rotates on chicken legs. In addition, the piece features Koshchei the Deathless, who has a key role in “Marya Morevna,” a better-known work in which Baba Yaga appears. But “The Frog-Tsarevna” can be grouped with those showing Baba Yaga’s kinder side, since her only role is to lend a hand to Ivan’s retrieval of the shape-shifting Vasilisa. There are no small roles — only small Slavic folklore figures. And Baba Yaga is not too high-minded to accept a small role.

The Footless and Blind Champions; Or, Baba Yaga as a Vampire?Our mercurial friend plays another minor part in “The Footless and Blind Champions” — again, not coming onstage until well after the curtain rises — but she’s far more sinister here. I’ll cut to the chase.

So a tutor named Katoma crosses paths with a very unpleasant princess named Anna when he helps his tutee win her hand in marriage. The tutee is another dude named Ivan (or, if it’s the same dude, he really needs to consider remaining a bachelor). Well, her Royal Unpleasantness orders that Katoma have his feet amputated. Luckily, he then meets a man who was previously blinded by Anna, and they work together to kidnap a merchant’s kind daughter, who presumably suffers from Stockholm syndrome, and the three settle into a happy domestic arrangement. You with me here? Yes, this is one of the wackier tales that, to be honest, I really love.

The trio’s happiness is short-lived, though. Following W.R.S. Ralston’s 1873 translation:

No sooner have the heroes gone off to the chase [for food], than the Baba Yaga is there in a moment. Before long the fair maiden's face began to fall away, and she grew weak and thin. The blind man could see nothing, but Katoma remarked that things weren't going well. He spoke about it to the blind man, and they went together to their adopted sister, and began questioning her. But the Baba Yaga had strictly forbidden her to tell the truth.By sucking her breasts, Baba Yaga drains the life out of the merchant’s daughter. I don’t recall seeing this vampirism in any of the other folktales I’ve read for this project. Furthermore, other than the name, there’s not much here to confirm that this the same Baba Yaga character as in those other stories. There’s no hen-legged hut, no flying mortar, no penchant for eating people, etc. However, there is a “fountain of healing and life-giving water,” which is key to the “Water of Youth, Water of Life, and Water of Death,” one of those tales in which Baba Yaga acts as a helpful guide.

The blind man and Katoma catch Baba Yaga and force her to divulge the location of the restorative waters. Even in this, she’s wily — but ultimately she guides them to the water that will give them back what Princess Anna took from them. Somehow, they promptly convert the princess to a repentant and more obedient life as Ivan’s wife. Katoma then marries the kidnapped merchant’s daughter. This seems very much a story about overpowering women and making wives of them, be they as dangerous as Anna or as charitable as the merchant’s daughter.

What happens to this oddly vampiric Baba Yaga? Presumably unmarriageable, she’s killed. Perhaps the best that can be said is: she’s been killed before, and that doesn’t seem to stop her.

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THE

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THEWHISPERS OF WITCHERY

MAIN PAGE.