The Missing Link in Three-Act Structure

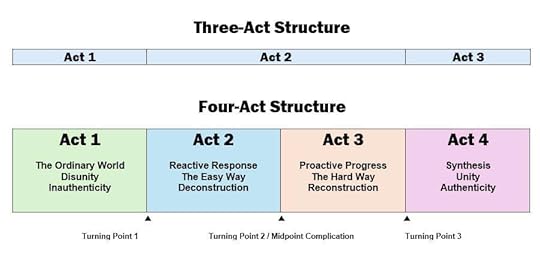

In any discussion of story structure, the three-act model inevitably dominates the conversation. Even as plotting methods such as Save the Cat, the Hero���s Journey, and the Snowflake Method gain popularity, the classic beginning-middle-end form reaching back to the dramatic theories of Aristotle remains the essential core.

But here’s the rub: Three-act structure produces a disproportionately large act in the middle of a novel���the double-stuff cream in the three-act Oreo���leaving writers with a puffy, gooey act notoriously recognized as the most difficult section to write. Act 2 of a three-act story is twice the length of the other acts, forcing writers to combat the infamous “saggy middle” effect using a hodge-podge of plot tangents and pacing tricks.

But it���s not the writing that makes the double-stuffed Act 2 feel like such a slog; it���s the structure itself. The loss of momentum is a symptom of a missing component that flattens plot and character development: the midpoint complication.

The Frog in the Boiling PotA well-paced story thrives on rising action, tugging readers into a web of progressively escalating complications. This stream of gains and setbacks turns up the heat on the protagonist, like a frog in the proverbial soon-to-boil pot of hot water.

But when complications occur solely at the scene level, readers may not feel as though their hand has been thrust against the blistering heat of the pot. Their experience is more likely to resemble that of our oblivious friend the frog���they may never notice the relentlessly mounting heat. They may lose interest and hop out of the story pot long before it comes to a boil and the frog finally takes action.

While fans of slow-burn stories do exist, most readers prefer regular injections of momentum. And the exciting change they���re looking for���the stuff that sends plots skittering in new directions and forces protagonists to grapple with impossible choices���is driven not by incremental temperature increases but by large-scale structural movement: story turning points.

What Do Turning Points Do?

Turning points are a structural element of storytelling. A turning point is a pivot point between two acts, forming a joint between one limb of the narrative and the next.

It���s not that a turning point is simply a dramatic, landmark event. That���s missing the point. A turning point fills a specific role in the story: It turns the story in a new direction. It keeps the story living, breathing, evolving ��� changing.

Turning points work on the basis of stimulus���response. The first element is a stimulus: a significant action, event, or revelation in the plot. The second element is the protagonist���s response to that stimulus. Their reaction determines the tenor and direction of the entire next act.

Recurring, well-paced turning points keep the story from deteriorating into a dull, predictable march toward an inevitable climax.

And this brings us back to the downfall of three-act structure.

The Midpoint ComplicationWithout a fundamental opportunity for narrative and character change during the second act of a three-act story, readers and writers are likely to flounder. But dividing the second act to create four acts instead of three creates an additional turning point���and another opportunity for the protagonist���s choices to determine the story���s direction.

The midpoint complication, which falls between the two middle acts, offers the perfect story shakeup. It sends the plot in a new direction or complicates the protagonist���s choices with significant new information.

Four-act structure eliminates the long, sagging middle act of three-act structure, prolonging the initial strategy the protagonist chooses at the end of Act 1. The midpoint complication injects new energy into the quest. Readers can visibly see the tides begin to turn. The protagonist���s initial attempts may not be paying off yet, but the hard knocks they���re taking are building determination and resourcefulness.

The midpoint complication serves as a crucial pivot, channeling the story���s energy from reactive response to proactive progress, from the easy way to the hard way, from deconstruction to reconstruction. This form helps writers avoid the common pitfall of the sagging middle act, buoying readers from the first act through the last.

The post The Missing Link in Three-Act Structure appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Writers Helping Writers

- Angela Ackerman's profile

- 1022 followers