Guest Post: Dealing with Stroppy Royals by Judith Arnopp

Those of you who have read my books will know that I tend to write about historical characters that we have come to regard as flawed, some might say ‘evil.’ Our twenty-first century sensibilities are outraged by actions which were perfectly within the bounds of acceptability at the time. Margaret Beaufort is the prime example of a woman whose historical record is spotless yet is commonly regarded as an obsessive mother with a cruel vindictive streak. One TV series even has her murder a man whom history records as dying in his own bed on a day when Margaret was many miles away. This type of character assassination is often dismissed with the words, ‘It’s only fiction,’ but as historical writers, fiction or otherwise, I feel there should be some authorial regard for the reputation of their subject.

Other than what I’d read in popular fiction, I knew very little about Margaret when I began writing The Beaufort Chronicle and my research revealed a very different woman to the one I’d expected. In book one, The Beaufort Bride, she is a child, married at a very tender age to Edmund Tudor. She is quickly widowed and gives birth to a son when she is still only around thirteen years of age. We throw up our hands in horror at this now, and there were murmurs against it at the time. Margaret herself, however, seems to have held no resentment toward Edmund. Even though the birth was traumatic and possibly ended her fertility, after two further husbands, she still requested to be buried with Edmund – a request that was denied.

Margaret deftly negotiated the war of the roses and the political upheaval that followed, managing to stay in favour with the Yorkist king Edward IV and his queen, Elizabeth Woodville. She worked tirelessly for the return of her exiled son, Henry Tudor, but it is not until the reign of Richard III that she began to manoeuvre him into the position to take the throne. Above all, Margaret was pious, loyal and generous, so given the current appreciation for strong women, our perception of her is surprising. Margaret was way ahead of her time when it comes to female rights; she certainly didn’t remain a victim for very long. The Beaufort Chronicle is a trilogy, written in Margaret’s voice, recording the events from her own perspective. She is sometimes blind to her own failings, as we all are.

When I completed the final book, The King’s Mother, I had come to know Margaret very well, or at least I’d come to know the woman who emerged from six years of research. History only provides us with facts that were recorded, as a historical fiction author I have to fill in the gaps and come up with a credible voice, and follow their path that was written long ago.

I am often asked how I manage to get inside my character’s head and convince the reader that they are listening to a historical voice. It is quite easy really. After I’ve studied the recorded facts, I sit down in an imaginary place, a tavern, or a garden for instance, and question my protagonist. How did that feel? Why did you do that? What were you thinking? What were you afraid of? Of course, fiction is only speculation. Any author, either of fiction or non-fiction, can only hypothesise about past events. None of us have been there.

After I’d finished The Beaufort Chronicle I became a little obsessed with tricky characters and wrote The Heretic Wind, which tells the life of Mary Tudor, better known as Bloody Mary. The list of atrocities she is accused of are damning; it is not until you consider her life as a whole and understand the events from her perspective that one begins to understand.

Aside from her traumatic upbringing, the religious upheaval she lived through had a pronounced effect on the passionately devout girl. We look on her today as fanatical and ruthless yet the historical record also speaks of her generosity, her compassion. Her actions against what she perceived to be heresy was bred of a deep love for her subjects. As far as Mary was concerned, the new religion would condemn her subjects to Hell. Hellfire has become a bit of a joke to many of us today yet in Mary’s time it was very real. God, Heaven and Hell, the devil, were all very real to Mary.

She had no concept of free thought. Her drastic measures were intended to deter her people from entering a pact with the devil. To us, the Smithfield Fires were abominable yet to Mary it was a last-ditch attempt to redeem her subjects from eternal punishment.

Noone can deny that Mary was wronged in childhood, deprived of love in her youth, and made miserable in womanhood. In The Heretic Wind, Mary is on her death bed when she narrates the story of her often miserable, seldom merry life. She is brutally honest, accepting her own failures, admitting her misdeeds but as she had been throughout her life, she is desperate for the approval of the listener/reader.

Once The Heretic Wind was complete, I walked away from the fires of Smithfield and turned my attention to the greatest perceived monster of them all, Mary’s father, King Henry VIII.

I will not pretend that writing The Henrician Chronicle was easy. It took four years to complete the trilogy and during that time, almost every day, Henry was in my head. It all got a little too real. Even when I put aside the laptop, he followed me into the shower, sat on my bed in the middle of the night. Sometimes he teased me, sometimes he flattered me and quite often he terrified me. Of all the characters I have written, Henry is the most complex; he was conflicted, frustrated and desperate to be loved. Blind, of course, to the misery he inflicted on others, at the end he was furious that fate had dealt him such a bad hand. By book three, his rage and hopelessness consumed both of us.

On a daily basis on social media I see Henry labelled a wife-killer, a philanderer, a monster. Nobody ever stops to ask what made him so, why he took the actions he did, what moulded him into the man he became? He is rarely judged from the standards of his day but from the obscure view of the modern world. Of course, I don’t approve of his actions or applaud him as a man or king but I try to understand him.

As I unpeeled the layers of negativity and uncovered the boy prince beneath, I discovered a likeable young man. He was fun loving, friendly, exuberant, and overflowing with good intentions, but as he led me through his life, I saw his hopes, his dreams, his grand plans for England shatter, one by one.

Henry craved the return of chivalry, a second Agincourt, he wanted to be remembered for glory, he dreamed of being a second Henry V. He also wanted to fill the royal nursery with miniature Tudors, boys in his own image. He didn’t like to fail, nobody does, and Henry had the power and the means to fight back, and fight back he did. He was nothing if not persistent. He fought for a son, he fought to regain territories lost in France, he fought against what he considered to be corruption in the church. He did not give up the fight until the very end.

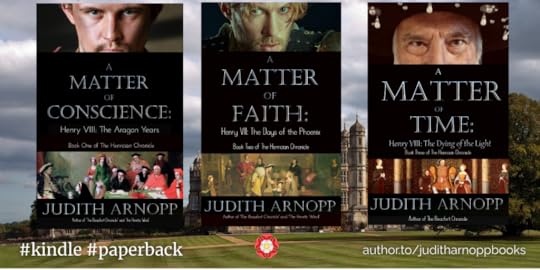

In the final book, A Matter of Time, the young prince we encountered in book one, A Matter of Conscience, is vanquished, the determined king of book two, A Matter of Faith, is laid low by pain and disease. He looks back at his life and realises he has failed to achieve even one of his goals. He is a failed husband, a bad father and an underachieving king. The only thing he has gained is notoriety.

Once the last book in The Henrician Chronicle was complete, I found myself at a loss. For several months Henry lingered in the corner of my mind, tainting my joy, refusing to go away but eventually he left. Almost immediately, another door opened and out stepped my current protagonist. Marguerite of Anjou – detested French queen of Henry VI, labelled a she-wolf, brought down by York, her son disinherited, her battles lost, her status diminished. She fought hard for her son, just as Margaret Beaufort fought for hers, but whereas Margaret won glory, Marguerite lost.

She ended her days a penniless pensioner of the French king, forgotten and alone. The popular perception of her is negative yet her actions were no worse than her male contemporaries; the only difference is her sex. Marguerite’s story is one of injustice, misogyny and treason, and I don’t think the war of the roses has been told from her perspective before.

So, after spending years at the court of Henry VIII, I am once more up to my neck in the war of the roses, encountering my old friends: Edward IV, Henry Tudor, Richard III, Anne Neville, and Margaret Beaufort. I hope to see you there.

Judith Arnopp – Author Biography

A lifelong history enthusiast and avid reader, Judith holds a BA in English/Creative writing and an MA in Medieval Studies. She lives on the coast of West Wales where she writes both fiction and non-fiction. She is best known for her novels set in the Medieval and Tudor period, focussing on the perspective of historical women and of course, from the perspective of Henry VIII himself.

Her novels include:

A Song of Sixpence: the story of Elizabeth of YorkThe Beaufort Chronicle: the life of Lady Margaret Beaufort (three book series)A Matter of Conscience: Henry VIII, the Aragon Years (Book One of The Henrician Chronicle)A Matter of Faith: Henry VIII, the Days of the Phoenix (Book Two of The Henrician Chronicle)A Matter of Time: Henry VIII, the Dying of the Light (Book Three of The Henrician Chronicle)The Kiss of the Concubine: a story of Anne BoleynThe Winchester Goose: at the court of Henry VIIIIntractable Heart: the story of Katheryn ParrSisters of Arden: on the Pilgrimage of GraceThe Heretic Wind: the life of Mary Tudor, Queen of EnglandPeaceweaverThe Forest DwellersThe Song of HeleddThe Book of ThornholdA Daughter of Warwick: the story of Anne Neville, Queen of Richard IIIMarguerite: Hell Hath No Fury (Coming soon)You can find Judith on most social media platforms.

Webpage: www.judithmarnopp.com

Books: author.to/juditharnoppbooks